Behind the Scenes:

40 Years of In These Times

Four decades of radical publishing

As told by:

John B. Judis

Salim Muwakkil

Susan J. Douglas

Slavoj Zizek

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Kurt Vonnegut

and more...

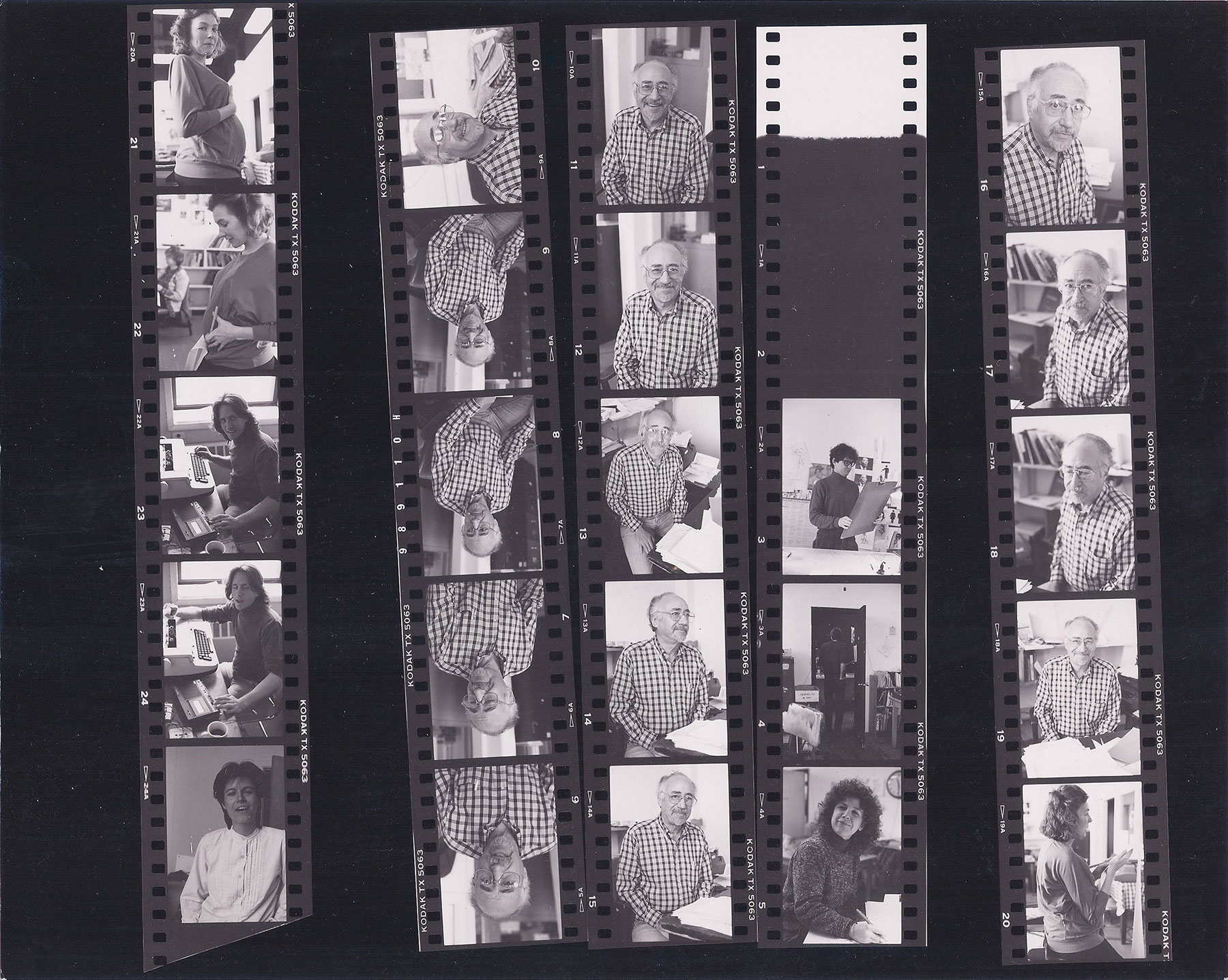

1980 staff photo by Steve Kagan (ITT Archives)

Behind the Scenes:

40 Years of In These Times

Four decades of radical publishing

1980 staff photo by Steve Kagan (ITT Archives)

As told by:

John B. Judis

Salim Muwakkil

Susan J. Douglas

Slavoj Zizek

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Kurt Vonnegut

and more...

December 31, 2016 | 40th Anniversary Issue

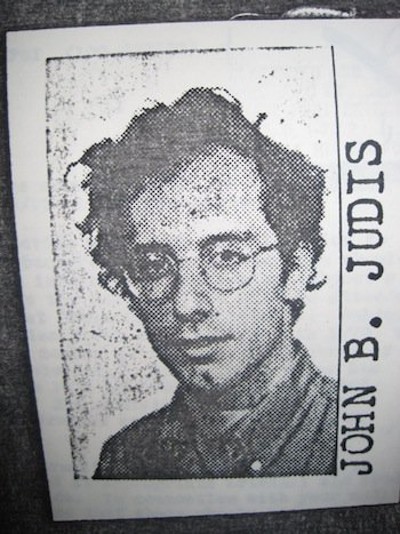

John B. Judis

West Coast Correspondent, foreign editor and Washington correspondent

James Weinstein (known to all concerned as “Jimmy”) already had the idea of a socialist newspaper, modeled on the Socialist Party’s Appeal to Reason, when I first met him in 1969, but he didn’t really start thinking about starting one until he went away to England as a visiting professor in 1974 or 1975. We corresponded about it, and one of things we argued about was whether it should be an explicitly socialist newspaper. Given Americans’ identification of socialism either with the Soviet Union or the crazy Left, I thought it would marginalize the newspaper. Jimmy thought that without a specific political goal, the newspaper would be reduced to the various causes and groups that characterized the left, each of which clamored to be more important than the others. Jimmy’s concern was a precursor of the current concern about “identity politics” reigning supreme on the left.

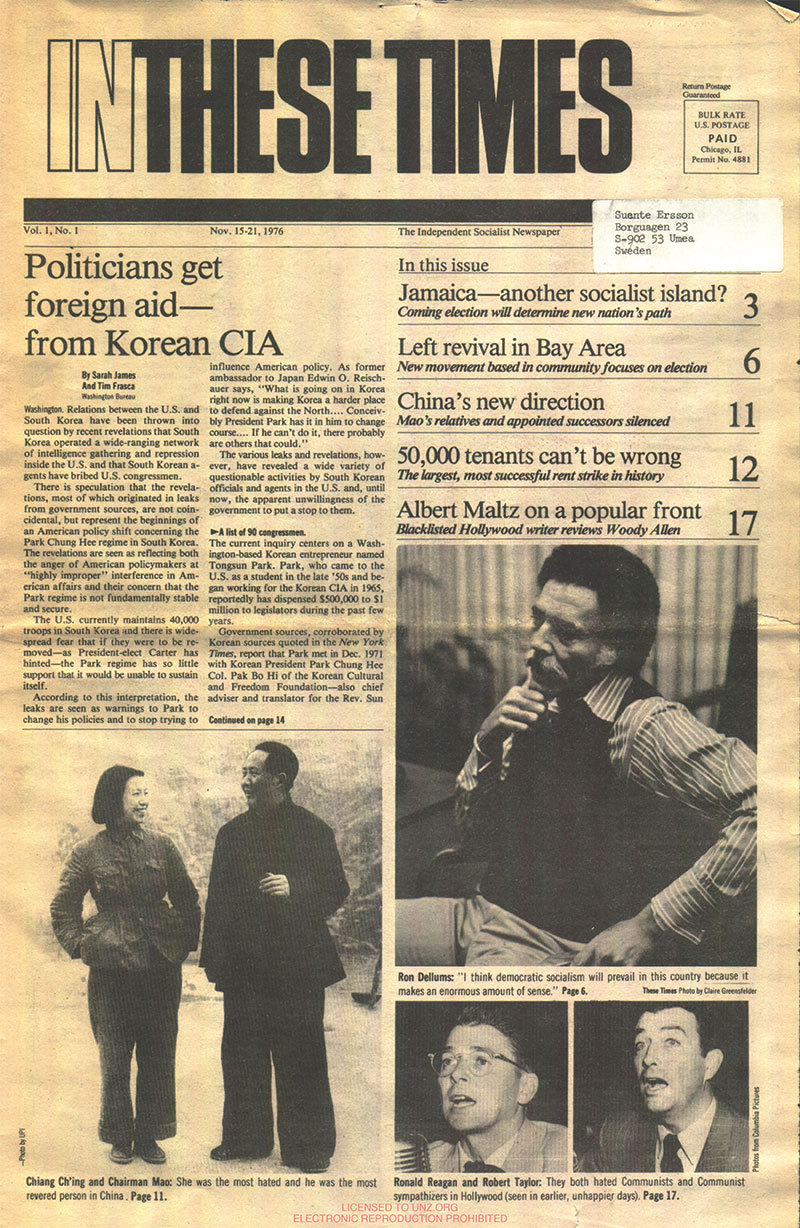

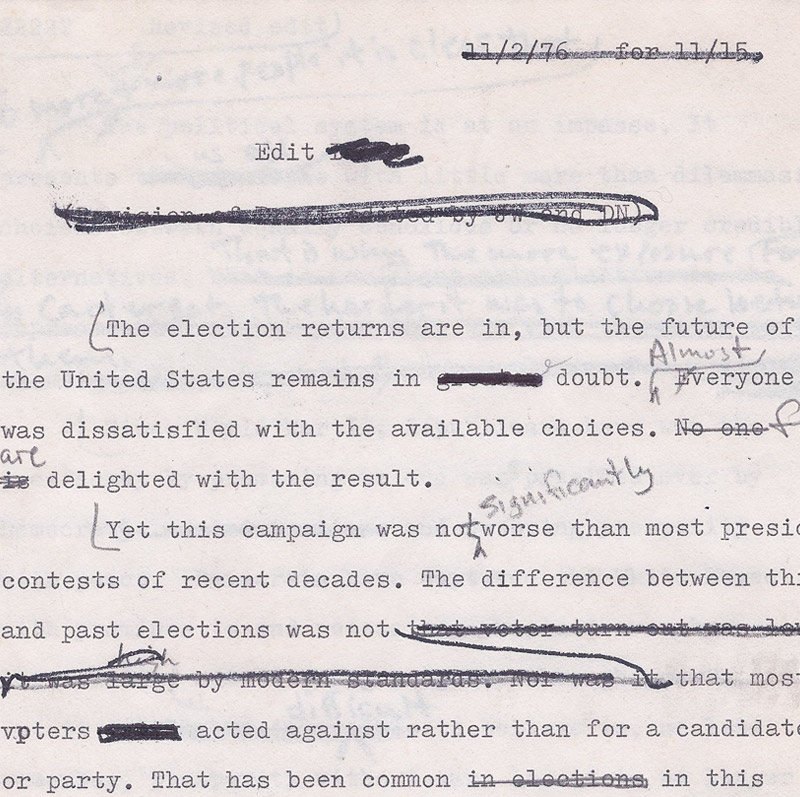

The first issue of In These Times, released November 15th, 1976

Jimmy won the argument and in November 1976, In These Times premiered as “the independent socialist newsweekly.” But by 1989, with Ronald Reagan in the White House, Jimmy came over to my side and a new subtitle, “With Liberty and Justice for All,” (from Pledge of Allegiance, written by Christian socialist Francis Bellamy) replaced the old. He did it for the same tactical reasons I had urged, but also because he had began to have doubts, as had I, about the model of socialism (featuring democratic central planning) that we had believed in. In later years, both of us moved farther away from our original socialist beliefs. Jimmy thought of socialism primarily as “socialist values,” and I defined myself as a Herbert Croly progressive.

I say all this because I think if Jimmy had started In These Times today, he and I would have agreed that it should be called “socialist.” The Bernie Sanders campaign has completely changed the discussion about socialism. It not only showed that the old stigma is disappearing, but that there is new, viable meaning to socialism based upon the achievements of European social democracy. These achievements, consisting of such things as a right to healthcare and education—regardless of income—are now under attack from business conservatives and from neoliberal converts among American Democrats (as well as European Labor and Socialist politicians) who believe that the needs of the global marketplace come first. I told Jimmy’s son and daughter last year that it was probably fortunate for them that Jimmy had not lived to see the Sanders campaign, because if he had, he would given his last cent to it. (That was in jest, of course.) The Sanders campaign was a vindication of his early vision of In These Times and of a public socialist politics.

Photo of John Judis, from his FBI file

Steve Early

Longtime labor reporter

One of the things I’ve most appreciated about freelancing for ITT over the years was the ability to be a “participatory journalist,” with protective pseudonyms. My cover story in 1997 on the tragic downfall of Teamster president Ron Carey was published under the pen name Jim Larkin, one of my favorites.

Writing candidly about labor struggles, internal and external, while still on active duty as a union organizer or representative can be perilous for one’s job security.

I was 28 when I first contributed an article to ITT, entitled “Violent showdown in Kentucky mine,” for the March 30-April 5, 1977 issue. The year before, I had written several times for the United Mine Workers Journal about the group of coal miners trying to form a new UMW local in response to the death of 26 fellow Blue Diamond Coal Co. workers at a sister mine, which exploded in 1976.

The piece I wrote about their later armed picket line at the Justus mine in Stearns, Kentucky in 1977 could not have been written under the name of someone then still in the part-time employ of the union, since it was the latter’s official position that only “gun thugs” hired by Blue Diamond were throwing lead.

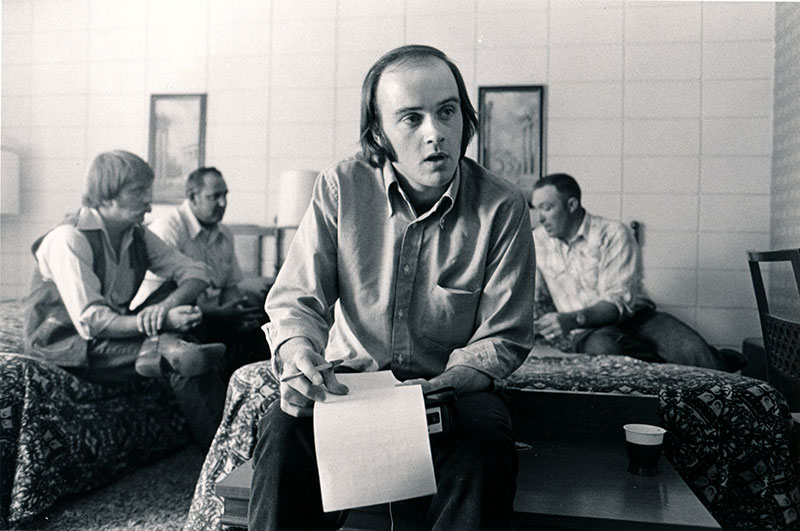

The several hundred would-be UMW members had been on strike for a first contract for eight frustrating months. As my anonymous report from McCreary County predicted, someone was “going to end up getting killed” due to the company’s use of trigger-happy Storm Security guards and the striking miners own formidable arsenal, which I managed to keep out of the picture in the on-the-job photo below, taken at the Holiday Inn in Williamsburg, Ky. When the NYT showed up a few months (and several dynamite blasts) later, management’s weaponry was certainly on display.

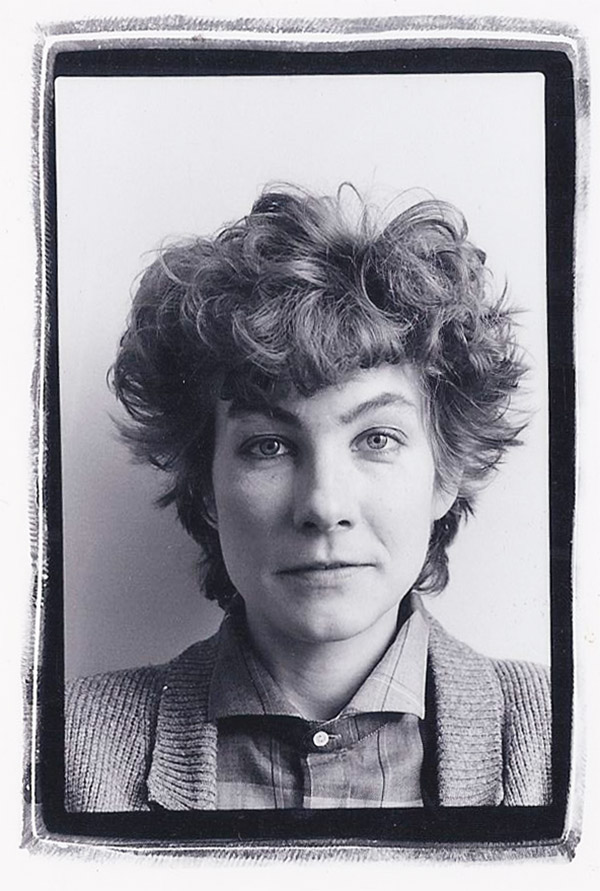

A young Steve Early, AKA Jim Larkin, AKA many others

Before this debacle ended, a company man was killed, several strikers went to jail on serious charges after injunctions and a state cop crackdown on the gun-play. Due to the lack of any strike tactics or strategy other than very traditional ones, a killer coal company was never forced back to the bargaining table.

My takeaway from this experience was that it takes more than a militant picket line to win a strike—even in an era when there were still more than 160,000 unionized coal miners in the U.S., instead of the small fraction of that number employed today.

In 1976-77, there was truly no justice or peace at the Justus mine in Stearns, Ky.

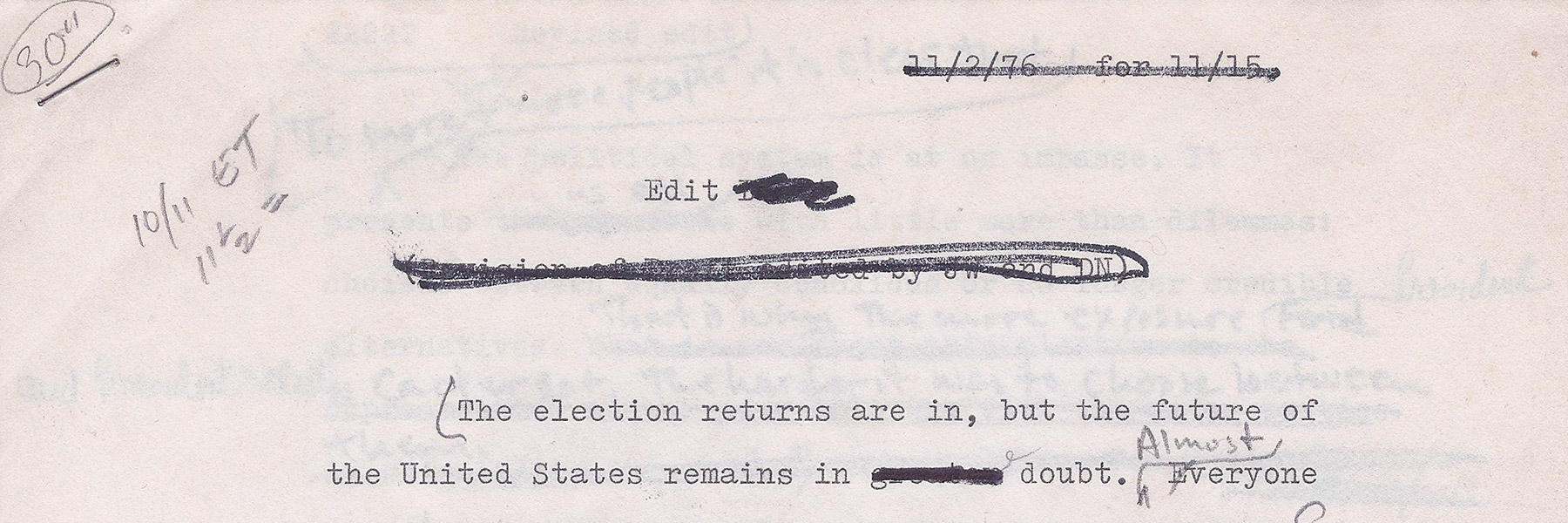

Hand-edited draft of James Weinstein's editorial from the first issue of In These Times

Nelson Lichtenstein

Contributor, 1989 to present

I am pretty sure I began subscribing to In These Times during its first year of publication. I have been an avid reader ever since, in print or online. ITT helped a generation of radicals and activists make the transition from the ’60s to the ’70s and beyond without dropping out of politics or moving to the Right. Although this might not sound like much of a compliment at first glance, the following is profoundly true: Strategists say that the most difficult maneuver for an army to make is an orderly retreat because it can so easily turn into a rout. ITT helped guide a generation through the difficult ’80s and in the process made them and those who followed ready to fight another day.

Hand-edited draft of James Weinstein's editorial from the first issue of In These Times

Pat Aufderheide

Cultural editor, senior editor, contributing editor 1978-present

It was 1978 and I was 30. I had just ditched a postdoc in colonial Latin American history to take a job as cultural editor. I thought I was being hired as a film reviewer; I didn't realize they were talking about an editor of a section till the end of the interview. They hired me anyway.

I did a lot of groundbreaking coverage, over years, of public TV—particularly of grassroots organizing of filmmakers to push public TV for more space on the schedule, which ultimately resulted in the creation of ITVS, the Independent Television Service. That activity wasn’t being covered by the entertainment press or the political press—it fell between stools—and of course, public broadcasting didn’t want the coverage. I was also honored to cover media arts organizations, including Kartemquin and Appalshop, not just the products they created, but the kind of space they created for underheard voices and viewpoints. I have had people tell me that they were inspired to become interested in communications policy because of my Media Beat column. I tried in it to make clear what a human process this is, with stakeholders whose effectiveness doesn’t just depend on the money they represent but their actual presence in the room, and a greater access to public-interest and nonprofit voices than many cynics believe.

ITT has been incredibly important in breaking stories. We covered Solidarity for years before the mainstream press did. We were all over Zimbabwe when Mugabe came to power. We knew Bernie decades before he was “Bernie!”

For me, ITT was profoundly shaping of the rest of my life’s work. I came to the paper dismayed and depressed by a polarization in left politics that had pushed many people into politically stupid and dangerous extremism. Working with Jimmie Weinstein gave me an understanding of a pragmatic, realistic but still hopeful politics. ITT was a weekly challenge to embody that approach; it was a practical experience of the politics of media every day, with plenty of feedback both internally and from readers. It was a richly rewarding, if sometimes trying, experience. I am extremely lucky to have benefited from it.

James “Jimmy” Weinstein (ITT Archives)

Gregg Pascal Zachary

Contributor, 1981-present

I met Jimmy in 1980, in a private home in San Francisco with a group of young writers (I was 25). Jimmy succeeded in charismatically motivating us, and in the 1980s, Thom Brom and later Joan Walsh (whom I worked with on the Santa Barbara News & Review) reported and wrote trenchant articles from the Bay Area for ITT. Brom managed to combine a fidelity to facts and logic with a passion for justice and a clarity of expression that I myself tried to emulate. To me, Brom is one of the unsung heroes of ITT's history.

Writing for ITT, certainly while Jimmy was alive, connected all of us to the radical history movement, and to the vital importance of context for any journalism, left or right. Jimmy inspired me when I began my own history project in 1989, which resulted in Endless Frontier, Vannevar Bush: Engineer of the American Century. So the connection between history and radical journalism, which he embodied, lives on in me and many other ITT contributors.

James “Jimmy” Weinstein (ITT Archives)

Eric Leif Davin

Contributor, 1978-1999

An article of mine from the early days I’m particularly proud of was one I wrote about attending a Ku Klux Klan rally in southwestern Pennsylvania. Cars were parked all along both sides of the rural roads leading up to the rally site for miles. The site itself was jammed with a mass of armed farmers and other rural folk. I was there in the midst of the robed Klansmen as they ranted and raved and set fire to the flaming cross in their midst.

I made no secret of the fact that I was a journalist writing for a lefty publication. My tape recorder was in plain sight. And yet they had no hesitancy in speaking with me and spilling their guts into my microphone. In These Times ran it in November 1980. I wrote many articles for In These Times back in the day, but this was the only time I got a center spread. I was very pleased. Until I noticed what no one at In These Times had bothered to notice. My byline had been omitted. Nowhere was my name on the article. So, if you do a digital search under my name for my best In These Times article, you won't find it.

The other article I remember trying to get was when I introduced myself to poet/novelist Marge Piercy during one of her reading tours. She was quite willing to be interviewed—until I revealed that it would be for In These Times. Her voice turned cold and she absolutely refused to be interviewed for the paper. “Why?” I asked. “Because the Left shits on its artists,” she said. And that was that, the ITT interview I never got. Ah, yes, those were the glory days of bearding the reactionary lion in its den for the radical press and being shut down by feminist authors. Too bad no one knew about it!

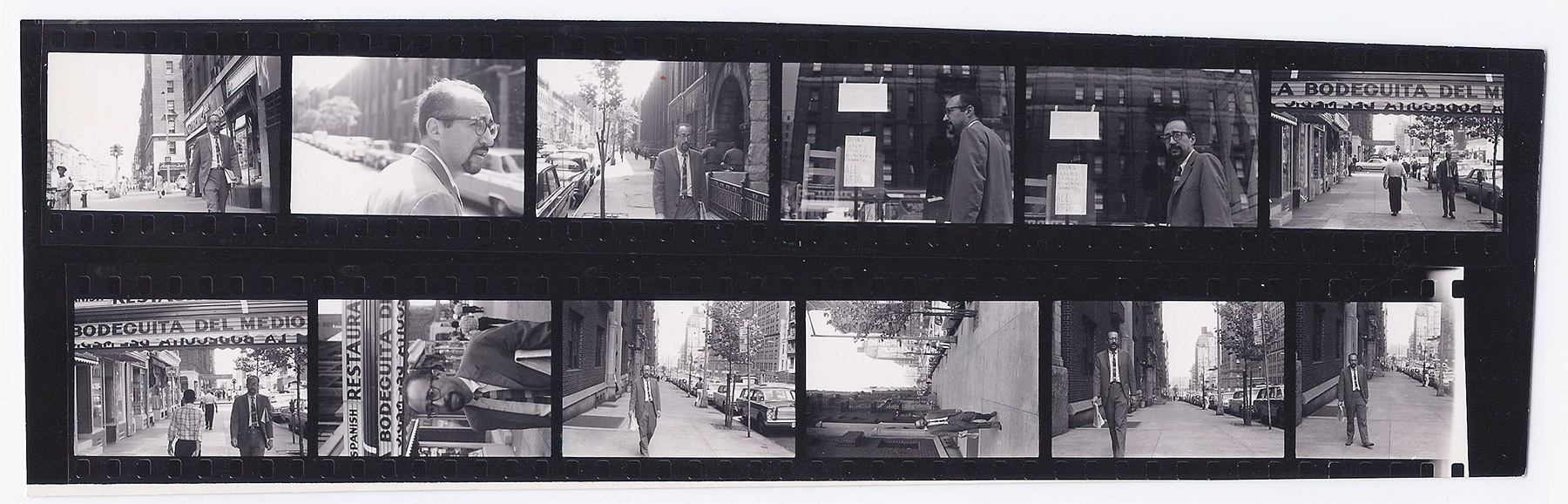

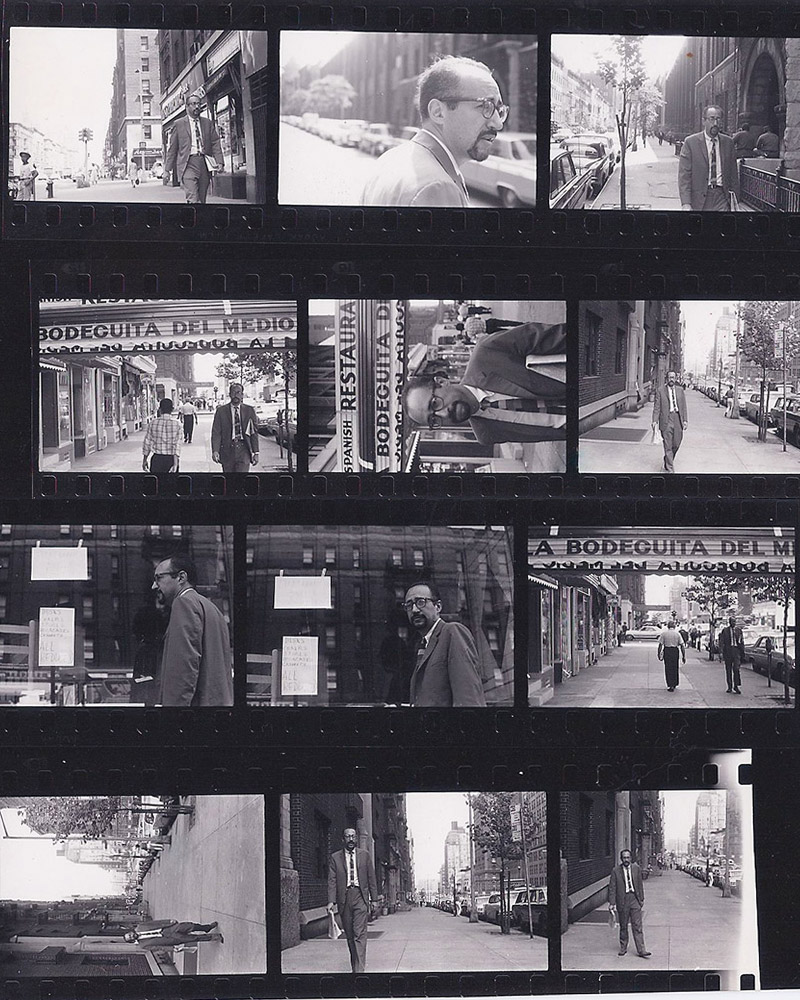

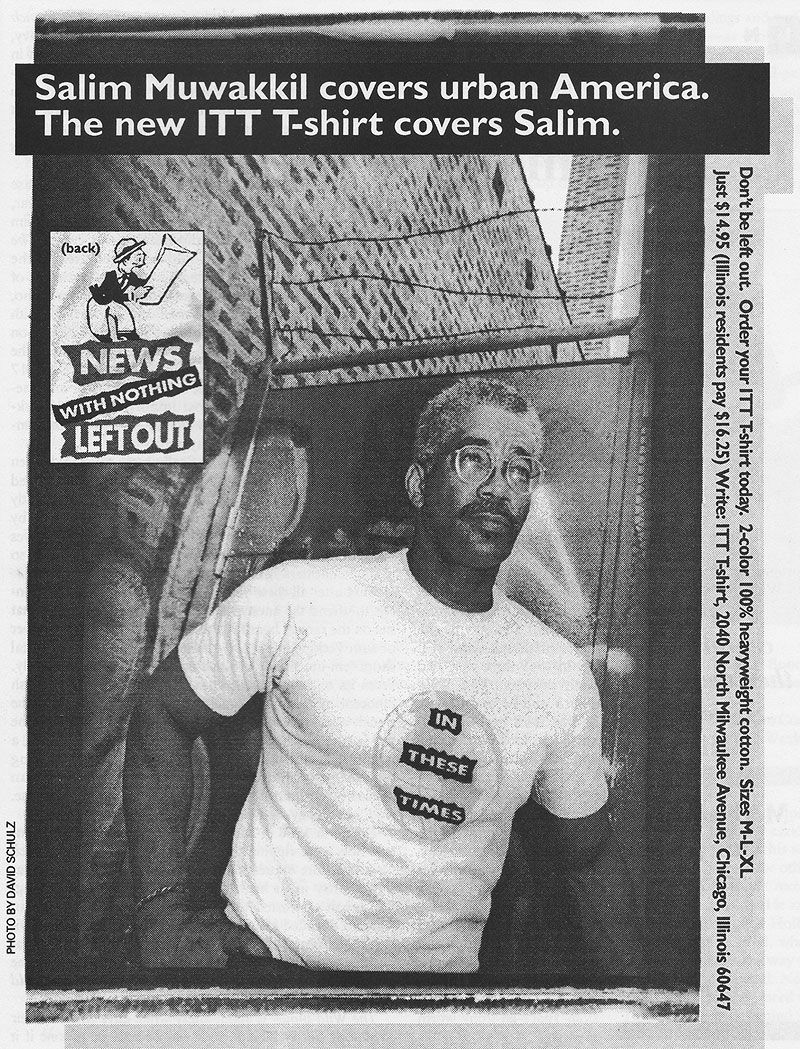

Salim Muwakkil

Senior editor, 1984-present

My first article for In These Times was a 1984 piece that examined the Nation of Islam’s support for Jesse Jackson’s presidential candidacy. The unique juxtaposition of Black Nationalist and progressive politics intrigued me. It also set the mold for my niche at In These Times. At the time, my gripe with the American left was its inattention to the nuances of racial oppression, and In These Times, with its non-sectarian approach to left politics, seemed to be the perfect venue to lay out those concerns.

I joined the staff later that year. It was during the stormy tenure of Harold Washington, Chicago’s first black mayor. One of my quintessential ITT moments happened following his 1987 re-election. I had completed an article addressing the concerns of Washington’s black critics, and the mayor died of a massive heart attack right before we were scheduled to go to press. We decided my piece was inappropriate and went into emergency mode to substitute another piece just in time. Whew! I became very familiar with that word.

I arrived at ITT as an experienced journalist, having worked for two years as a news writer for the Associated Press, four years with Muhammad Speaks (one of those years as managing editor), as an editor for the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and as a pretty prolific freelancer. I was 37. I started out as “culture editor” but moved either to senior—or contributing—editor (I don’t remember which) soon thereafter.

Salim Muwakkil in 1995, looking fit and showing off the latest ITT t-shirt

I’m proud of many articles I’ve written, but I suppose three 1989 articles are noteworthy for their historical importance: one, “What’s In a Name,” chronicled the process by which representatives from dozens of the nation’s major black organizations gathered (under the auspices of Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition) and agreed that “African-American” was the most appropriate nomenclature. Another was “Blacks Call for Reparations,” one of the first national stories on that issue, and the third was “Central Park: story of fear in black and white,” about the panic surrounding an alleged rape of a young white girl by five “wilding” black youth in New York’s Central Park. (Donald Trump famously bought ads in four New York dailies urging the return of the death penalty as punishment for what turned out to be false charges.) I’m also proud of “Call To Order,” an April 1995 article exploring the growing popularity of Louis Farrakhan, “The CIA and the Crack Epidemic,” a September 1996 story that focused on the late Gary Webb’s bombshell expose of how crack came to the United States, and “Color Bind: The Other Side of ‘Zero Tolerance,’ ” an October 1997 piece illuminating police brutality.

For 40 years, ITT has been a reliable vehicle for valuable progressive critique of U.S. politics and culture. The spirit of intellectual curiosity nurtured by the dedicated staff attracts thoughtful contributors whose insights add needed texture to the national discourse. What’s more, ITT’s non-sectarian character has made it an indispensable venue for useful self-criticism. The U.S., nay—the entire planet, would be severely disadvantaged were ITT not to make its 50th anniversary, and beyond.

Miles Harvey

Assistant managing editor 1986-1989, managing editor 1991-1994

A lot of gifted journalists have helped shape In These Times over the years, but few have had a bigger impact on the publication—or on her coworkers—than Sheryl Larson, who died this past June after a 22-year battle with breast cancer. As managing editor for more than a decade in the 1980s and 1990s, Sheryl was the driving force behind groundbreaking, in-depth articles on subjects as climate change, the AIDS epidemic, the Iran-Contra arms scandal, Agent Orange and the Times Beach dioxin disaster.

I began working for In These Times in the fall of 1986, when Sheryl hired me to be her assistant managing editor. (I started the job, in fact, on the same week as another of her protégés, current Editor & Publisher Joel Bleifuss.) I've worked with many magazine and book editors since, but no one taught me more—both about how to edit copy and how to work with writers—than Sheryl did. One of the biggest things I learned from her is that each story is different and that you have to listen to what the piece is trying to say—even when the author himself doesn't seem to have clue.

Tough, astute, funny and complex, Sheryl was a brilliant conversationalist, a woman with myriad interests and countless friends. She was also, hands down, the most glamorous editor of a socialist news magazine who ever lived. Not only did she have physical grace—a seemingly effortless elegance and dignity and poise—but she also had great taste. Great taste in clothes, great taste in food, great taste in interior décor. Great taste in a husband (Hank Kinzie). And, of course, great taste as an editor. Nor did Sheryl see good taste and good politics as a contradiction. She loved beauty with the same passion that she hated inequality and injustice.

Sheryl Larson (ITT Archives)

The last time I heard from her was a few days before her death when she sent some friends an e-mail with the subject line, “don’t miss this one.” There was no text—just a link to story from the Atlantic magazine about the troubled mind of Donald Trump. It was typical Sheryl: still outraged, still engaged, still in search of great journalism.

Maggie Garb

Publishing department, 1987-1989

I was 25 in 1987 when I started work at In These Times, unsure of myself and unsure of what I was expected to do at the paper. Jimmy hired me to promote the paper and its stories in the mainstream press. He sent me to New York to meet with Micah Sifrey, who then had a similar job at The Nation. But Micah was in New York, was confident and had lots of journalist connections. I had none of that.

My first and biggest success on the job had little to do with me. It came when Anthony Lewis, then the leading liberal columnist for the New York Times published a column citing In These Times’ reporting on the “October Surprise,” the story that the Reagan campaign had communicated with someone in Iran and urged the Iranian hostage-takers to hold onto the American hostages in the Iranian embassy until after the 1980 election. In These Times was, I think, the only news outlet chasing that story. When I called to thank Lewis for his mention of In These Times, he told me that he kept a file of In These Times in his office and read the paper regularly. I do not know for sure, but I suspect he was the only major news person in the U.S. to read ITT regularly. The October Surprise story later appeared in other news outlets but never got the national attention it deserved.

On the Iran-Contra scandal, ITT was out in front of the rest of the national press, documenting the corruption and law-breaking of Reagan administration officials. ITT’s coverage seemed to push reporters at other news outlets to take seriously Iran-Contra, even before a special prosecutor launched an investigation.

I have clear memories of Sheryl Larson walking through the offices on Belmont, carrying a baby in one arm and holding up a sheaf of papers, news copy, in the other. She taught me to write and to dream of what my life might be.

Now I teach American history at Washington University in St. Louis and my activist students are always amazed to learn that I, long ago, worked for In These Times. To my students, the paper is an institution, a pillar of the American left.

Susan J. Douglas

Senior editor and author of the “Backtalk” column

My first piece for ITT, “Blonde Ambition,” was published in 1987. Vanity Fair had just published a gushing cover story about Diane Sawyer; inside was a piece about Donna Rice, the young woman who was photographed cavorting with then married presidential candidate Gary Hart. The class-based difference in coverage of the two women was staggering (even though Rice was Phi Beta Kappa) and I sought to expose that. I didn’t hear for a while about the piece until then-culture editor Jeff Reid called and told me it had ended up in Salim Muwakkil’s mailbox by mistake (remember; this was way before email attachments!) This was my first journalistic piece and opened up numerous opportunities for me to write media criticism; I will always be grateful that ITT took me on. I am especially proud of the magazine’s fierce, unwavering progressivism and that Utne Reader has nominated it multiple times for its media awards, which the magazine won in 2006.

Pete Karman

ITT Ideologist

I recall (not perfectly at 77) that this lifelong lefty began writing for In These Times in 1977 and briefly became an assistant managing editor in 1989. ITT was still on West Belmont then. Fellow editor Miles Harvey said the neighborhood was in transition from red light to Bud light I remember that most of the incoming and outgoing phone calls were for Joel Bleifuss. It was humbling for this tabloid-trained scribbler to witness a nonpareil investigative reporter at work. Then there was Jimmy Weinstein. Both being wise guys, we hit it off right away. He had that wry smile that said he knew what was happening. Twenty-five years later, I still keep my hand in as resident ITT Ideologist, a writing job that calls for a bedeviling admix of political correctness and incorrectness, plus yuks. You try it. (Pete also fitfully writes a blog called The Karman Turn.)

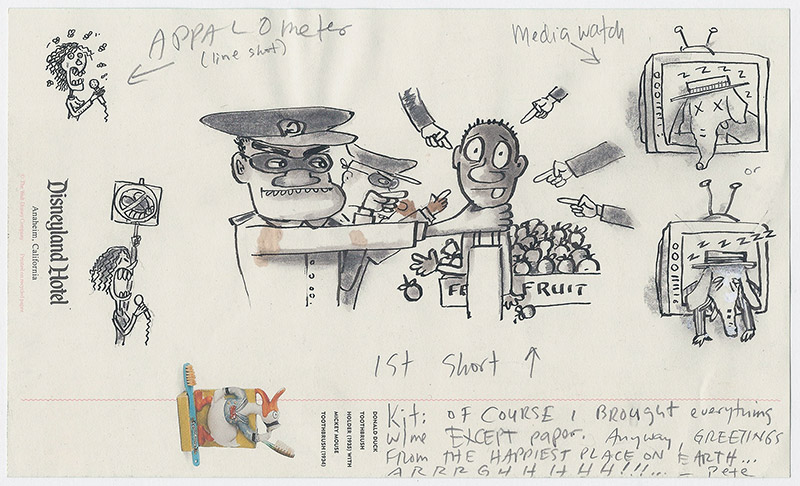

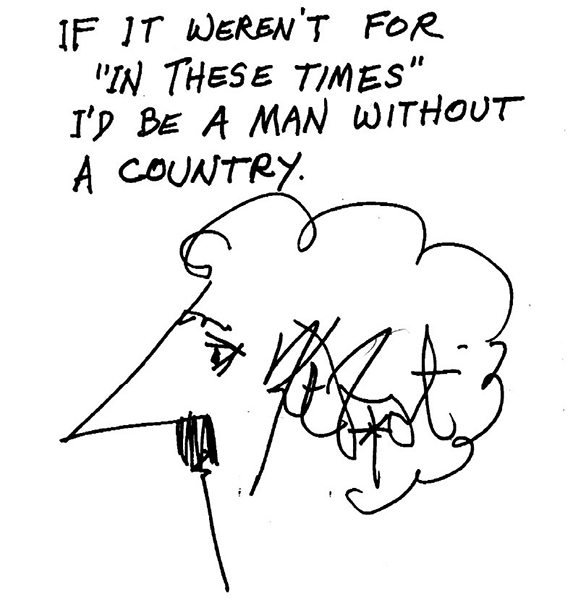

Pete Karman's original art for an issue of In These Times, hand-drawn on Disneyland stationary while on vacation with his family

Peter Hannan

Art department, 1980s and 1990s

Working at In These Times was a lot like producing TV ... a bunch of funny, serious, overworked people running around like maniacs, somehow pulling off imperfect miracles week after week. I was there for some of Reagan, all of Bush I, and some of Clinton. Reagan was the most fun because of the contrast between the kindly grandpa image and the monster. I remember getting deep into mad art zones, cranking out way too many layouts and drawings per hour. Another favorite memory sounds like something Frank Capra cooked up: When the mail arrived, Jimmy and any other contestants who cared to join in would start ripping open envelopes, gameshow-style, hoping for a grand prize or at least a little something toward the week’s payroll. “Come on, baby, come on ... ding-ding-ding ... fifty dollars!”

Pete Karman's original art for an issue of In These Times, hand-drawn on Disneyland stationary while on vacation with his family

James Weinstein and others at the In These Times offices (ITT Archives)

Terry LaBan

Art department, 1990-1992, cartoonist and illustrator, 1990-present

In These Times was only 14 years old when I wandered in in early 1990. I was 28 and had just moved to Chicago from Ann Arbor with my girlfriend. She was going to get a Masters of Social Work at the University of Chicago. I was, hopefully, going to make some semblance of a living drawing cartoons and, looking for freelance illustration work to support that ambition, I called up In These Times.

I was familiar with the paper because one of my college housemates was a subscriber and I often thumbed through the back issues of the then-tabloid that littered her bedroom floor. I knew they used illustrations and though the ideology of potential clients was not one of my big concerns, the fact I sympathized with their politics was certainly a plus.

I was invited to come down, so I gathered up my portfolio, drove down to what turned out to be an old building on a grimy strip of Milwaukee Avenue and went up a set of creaky wooden stairs. The inside looked better than the outside—the paper had only moved in a short time before—and I immediately liked the friendly bohemian types who staffed the art department. They complimented the samples of the political cartoons and illustrations I’d done for the Ann Arbor News, but said they did most of their stuff in-house and didn’t hire many freelancers. I thanked them and left, figuring that was that. But much to my surprise they called me a couple of days later and offered me a job.

Never would I have imagined that 12 hour-a-week part-time gig shooting photostats (look it up), pasting up the paper (literally, with wax) and doing illustrations and cartoons, would become a relationship that would last, in one form or another, for the next quarter century. There were lots of times it could have ended. When In These Times went digital in 1992, the waxed typeset and photostats were out, but I was still given regular work doing political cartoons and illustrations. The by-now magazine went through hard times and the illustrations were cut back, but I still did cartoons. Eventually, the cartoons were cut, but I still did something for the funny news and later letter section. Given In These Times’ perilous finances, I always half-expected to arrive one day to find the doors chained up and the phones disconnected. And yet, here we are.

When I actually worked at In These Times, I liked it. It was a good place to hang out at the end of the first Bush presidency and the beginning of the Bill Clinton's, when the Cold War was barely in its grave and free market conservatism had apparently triumphed, at least as far as the majoritarian view was concerned. My colleagues at the paper, especially the ones in the art department, were cool and funny. We went out for lunch, had great conversations, and worked late the day the issue went to the printer. When important events were in the offing, someone would bring a TV in and it was comforting to be with like-minded people while watching the Rodney King riots and the assault on the Koresh compound at Waco. When I stopped having to be in the office I still came in regularly to drop off my original art, say “hi,” and dig through the slush pile of books sent in for review, where I often found something worthwhile. As the years passed and ever more work was done remotely, the onsite staff dwindled and the big office, once full of busy lefties, grew emptier. The folks I started with left to become professors, create Nickelodeon cartoon shows, manage their buildings or who knows what, and when it became feasible to send my work in by email, my visits grew infrequent. Eventually I moved to another city, and my direct contact with In These Times was finally limited to what was in my inbox and the issues that came in the mail.

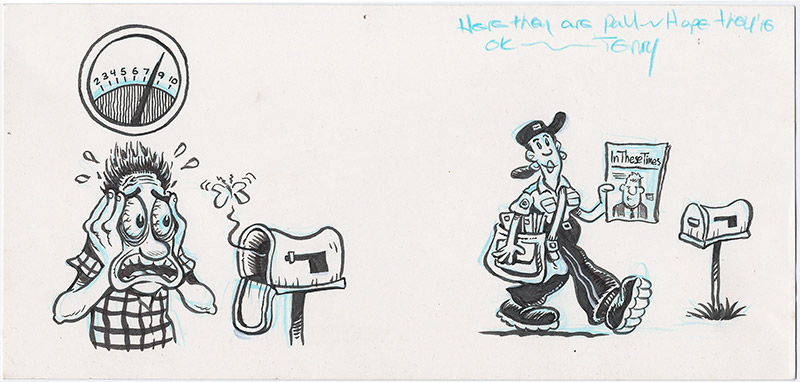

Original art for an issue of In These Times, by Terry Laban (ITT Archives)

And yet, much to my surprise, it’s still there and I’m still drawing for it. My gig with ITT has outlasted my kids’ childhoods, a career in comic books and a long stint as a syndicated cartoonist. It’s encompassed my youth, young adulthood and, at this point, a fair chunk of my middle age. Like any long-term relationship, it’s had it’s share of frustrations, but I’m grateful for the opportunities it’s given me to grow and develop my work and to have at least one place where my illustrations could always be seen. As you get older, the connections you've had the longest only get more valuable. There are just a handful of high school and college friends I've stayed in touch with longer than I’ve worked with In These Times. Including that girlfriend I followed to Chicago in the first place—we’ll celebrate our 25th anniversary next year. So happy birthday, In These Times. It’s been a great ride and if I'm still appearing in your pages 25 years from now, I will, for all kinds of reasons, be very pleased.

Craig Aaron

Managing editor, 1997-2003, editor, Appeal to Reason: 25 Years In These Times (Seven Stories, 2002)

How important was In These Times in my life? It was my first real job. It was my graduate school. It was where I met my wife.

Where else could a 23-year-old edit Noam Chomsky? Talk politics with Kurt Vonnegut? Drink gin-and-tonics with Studs Terkel?

As the magazine’s 25th anniversary approached, I set out to read every issue from the start, collecting the best for a book. For two years, I pored over the archives, breathing in the old newsprint, marveling at the old bylines and soaking up the unique on-the-ground view of the American Left from the early days of optimism and in-fighting to the dark Reagan years to 9/11.

So many amazing writers got their start—and the freedom to write what they wanted—in these pages.

My one regret with that project (besides that typo on the back cover) was not completing an oral history of the magazine to capture all those big personalities behind the scenes.

I don’t remember all the articles anymore, but I’ll never forget sitting at a Polish buffet with Jimmy Weinstein and hearing about when he drove around Julius Rosenberg; the time Paul Wellstone pulled me aside and whispered: “David Moberg is a great American”; and all those delirious late nights putting the magazine to bed and hoping a burglar wouldn’t drop through the ceiling. (It only happened once.)

Oh, and those amazing chicken sandwiches and tostones at Irazu, the Costa Rican place down the street. With a guanábana shake. I can taste it now.

Kurt Vonnegut

Senior Editor 2004-2007

James Weinstein and others at the In These Times offices (ITT Archives)

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Longtime reader

In college I worked at a bookstore in D.C., and it was my job to tear off the covers of unsold magazines so they could be mailed back for refunds. I would take the cover off In These Times and take the rest of the magazine back to my dorm room—and that was my introduction to the Left. Left media institutions like In These Times are incredibly important, then and now.

David Kallick

Contributor, 1997-2000

Summer 2001.

The scene: Jim Weinstein, Joel Bleifuss and me at a public presentation in Copenhagen, the three of us trying to explain to Danes where is “the Left” in America, and what went wrong in the 2000 election. Joel explaining to a slack-jawed audience how the American electorate was charmed by a candidate not despite, but because he didn’t seem to be any better informed than the average person on the street. Me pursuing my longstanding obsession about bringing together Scandinavian-style social democracy with America’s great strengths—pluralism, individual initiative, and a robust civil society. And Jim arguing that, despite all signs to the contrary, the future of socialism is in America.

After the presentation, the three of spent a long evening talking over drinks with our Danish hosts. What does “socialism” mean today? Is it appropriate to have a Pakistani health center, or should there only be equally funded and similarly run government health centers where needed? Would a magazine like In These Times exist under socialism? If so, who would own it?

The event was titled: “U.S.A. In These Times.” Put on by Social Kritik magazine and the Danish newspaper Information, the idea was to bring some of the spirit of the “In These Times Left” to a Danish public, and to extend a conversation with our colleagues in Denmark. What the Danes knew of the Left was the Democratic Party. (Here’s a link to the Danish article about that forum, from Information.)

Even in Copenhagen, the magnetic field of In These Times created a forum for far-reaching political discussion and, of course, also political argument. The setting was a welcome reprieve from the narrow confines of American political debate. But through it all Americans and Danes alike couldn’t stop shaking our heads and wondering: Bush? Really?

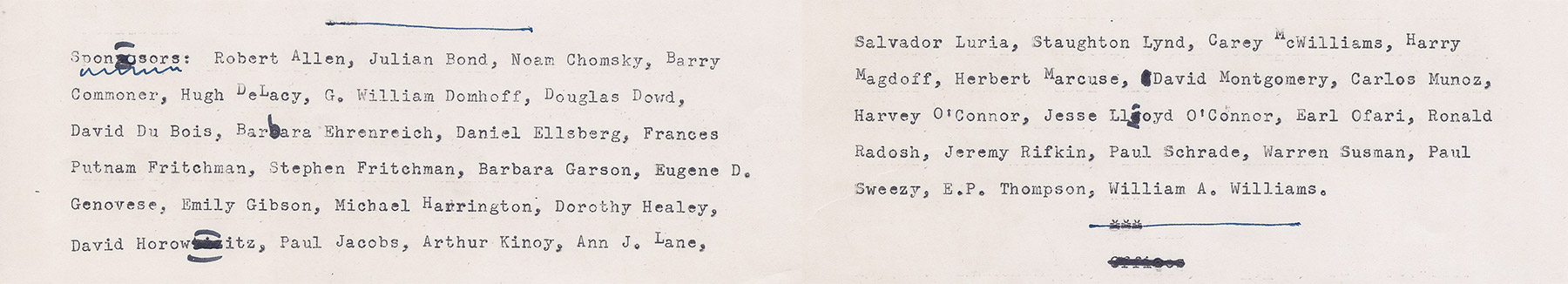

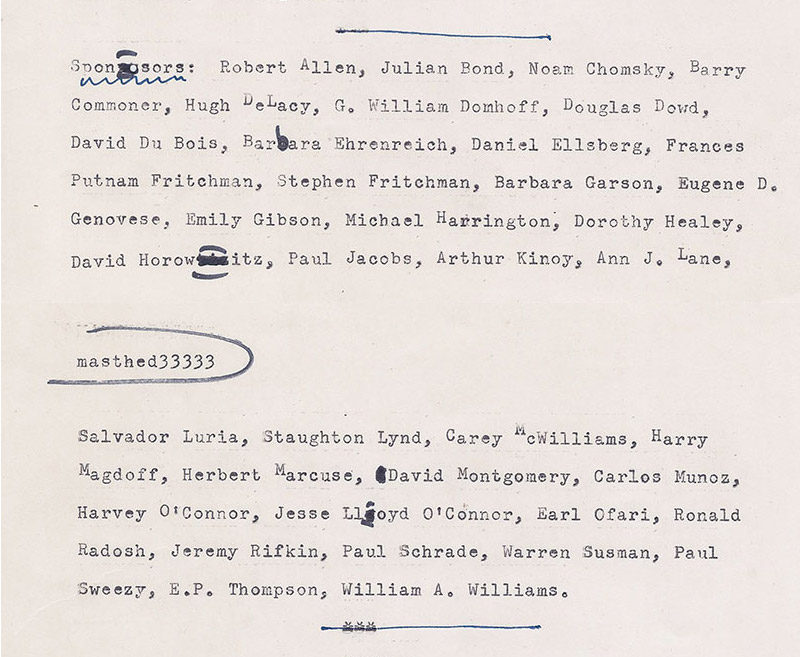

Early In These Times sponsors, from a type-written version of the original masthead (ITT Archives)

Slavoj Zizek

Regular contributor, 2003 to present

The reason I am honored to collaborate with In These Times is that, while it consistently pursues a radical emancipatory agenda, the journal retains the critical stance towards many standard leftist premises. It combines the ruthless and consequent critical analysis of the new world order with a no less ruthless examination of how much of the Left, even if it presents itself as radical, secretly participates in the order it publicly denounces. Only such a self-critical stance can sustain hope in our dark times.

Brian Cook

Editorial assistant, assistant editor and associate editor, 2003-2009

ITT one of those rare U.S. institutions founded on the premise that capitalism and massive militarism are not “normal” or “natural” states of being. ITT doesn’t take these systems for granted, and strenuously argues that they can, and should, be changed to create a more just and humane world.

Chris Hayes’ essay “The Good War on Terror,” which examined how the ‘90s nostalgia for the Greatest Generation helped pave the road culturally and ideologically for so much of the madness that would come after 9/11, serves as a nice example of the type of commonsensical but far-too-marginalized work that ITT regularly publishes.

Early In These Times sponsors, from a type-written version of the original masthead (ITT Archives)

ITT is also often prescient. Rashid Khalidi’s “Attack Iraq?” was published about two months before the United States began its brutal “Shock and Awe” campaign on the people of Baghdad. In its clear-eyed view of what the likely consequences would be from a U.S. invasion, the article reads today as if it was written by Cassandra. (Perhaps Khalidi is her nom de plume?) It is a timely reminder that all the carnage and chaos engendered by that war was quite predictable beforehand, and was indeed predicted.

David Mulcahey’s “Tranche Warfare” examined the likely consequences of a collapsing housing market and subprime-backed “collateralized debt obligation” meltdown. If you were reading ITT (and Dave’s article) in the summer of 2007, you didn’t need to wait for The Big Short to explain the mechanics of the 2008 financial meltdown to you. Indeed, Dave not only broke it down but warned darkly, “Some speculate that hedge funds are hugely freighted with subprime waste, and that a rolling implosion is in the offing… A credit crunch is possible, which in turn raises the specter of recession.”

In These Times promotional postcard

Even more darkly, he concluded: “A reckoning is on its way. And there’s an old saw on Wall Street that, in times of panic, money returns to its rightful owners. Let’s not have any delusions as to who that might be.” So the news that the top 1% captured 91 percent of all real income gains from 2009 to 2012 might have been surprising to some, but not to any readers of In These Times.

As for memories of ITT, I’m still making great memories with so many of the people I worked with there. Hell, just this summer, I went to Oakland for the joyous wedding of former ITT associate publisher Erin Polgreen to former ITT editorial intern Brian O’Grady, which was attended by (at least) six other ITT alums; had a great dinner in North Carolina with former ITT associate publisher Aaron Sarver and his wife, who he met at a Media Reform conference on ITT’s dime; and went to Wrigley Field to watch former ITT Senior Editor Chris Hayes throw out the first pitch at a Cubs game. So I guess my main memory of ITT is that it creates a special bond among the people who work there, one that endures long after you’ve left. You might even call it, Solidarity.

Jessica Clark

Publishing department, 2002-2003, managing editor, 2003-2006, executive editor, 2006-2007

In These Times was a tremendous opportunity for me—I learned to argue for my perspective, to edit until the thing got good, and to revel in ideas there. I met some of my closest friends and co-conspirators there. It was core to my life and work.

Sanhita SinhaRoy

Managing editor, 2007-2009

My fondest memories of working at ITT will always be the meetings that took place behind the scenes, particularly discussing editorial pitches and brainstorming headlines—from the unambiguous (“Death Squads in Oaxaca”) to the clever (“ICE Cold to Kids” or “Big Trucking Deal”). No pun was too ridiculous to share. And while I’m most proud of reining in the long nights to help the magazine meet all of its printer deadlines (as was my task as managing editor), I secretly also enjoyed the occasional late evening, going through stock photos with the art director and other colleagues to find the right image to go with a story. Plus wrapping up an issue usually meant ordering takeout and picking up beer.

In my 16 years of being an editor and working at five magazines, I’ve never experienced the same level of camaraderie as I did at ITT. Colleagues and interns were whip-smart and passionate about peace and social justice, and they also knew how to relax and have a good time.

Dan Dineen

Intern, 2008, deputy publisher, 2008-2013

I first found In These Times early in college, during the darkest days of the Iraq War. I was immediately attracted to the clarity of its opposition. As I got to know the magazine more, especially its coverage of labor, I began to feel as though ITT was the conscience of the U.S. Left. I've always respected that this consciousness extends beyond the beltway to the movements and struggles emanating from smaller cities and rural regions throughout the country.

The most immediate and lasting impression from my experience at In These Times is the enormously satisfying experience of closing the magazine each month. The cycle of producing such a vital, substantive document was addictive. After closing my first issue in January 2008, I was hooked. I suspect this is true of a lot of past and present In These Times staff members. There are many other things I loved about working at ITT—the urgency of the work, the debates about pieces, the brilliant and wild pitches, the curiosities of ITT HQ, the headline meetings. All of this created a shared sense of purpose among the staff that made long deadline nights not only endurable but enjoyable. None of this would be possible without ITT’s wonderful readers, who are committed to the magazine’s quality and its mission, and are generous in support of both.

Jeremy Gantz

associate editor, 2008-2012, editor, The Age of Inequality: Corporate America’s War on Working People: A 40-Year Investigation by In These Times (Verso, 2017)

2009 was a very, very bad year for In These Times: The economy tanked, donations dropped and the staff shrank. We ended up a skeleton crew of just four full-time employees. Job descriptions became increasingly theoretical: We did whatever had to be done to keep the wheels on. A photo of us made its way into a holiday card for major donors above the half-jesting caption “In These Times’ staff is small but mighty.”

The staff has since grown, thank god. I now feel rather sheepish for ever thinking the magazine wouldn’t make it past its 33rd birthday. I was too focused on cash flow (i.e., my paycheck) to realize that In These Times’ ethos and reputation let it flout the normal laws of economics, at least for a little while. There were volunteers everywhere: the board of directors, proofreaders, a newly minted “board of editors,” and, of course, interns. All pitching in because they wanted to make the idea of In These Times a reality. They wanted to be part of something that has the power to change the world. Small but mighty, indeed.

The “small but mighty” In These Times staff, circa 2009. Left to right: Joel Bleifuss, Dan Dineen, Rachel Dooley, Jeremy Gantz (ITT Archives)

Liz Novak

Development director, 2011-2012

Where would I be without In These Times? I wouldn’t know about “stripper solidarity” at the Lusty Lady, I might have trouble remembering what ALEC is, and I certainly wouldn’t know the heart-wrenching stories of mothers balancing care for their newborns while trying to remain gainfully employed. Thanks for 40 years of exposing corruption and advancing justice. Here’s to 40 more!

Alex Lubben

Deputy publisher, 2013-2015

Three days after I started my editorial internship at In These Times I was sitting down with Joel, poring over the magazine's annual budget. As usual, there wasn’t enough money.

I was 22 when I started at ITT, fresh out of undergrad, with no experience with anything relating to the magazine business, or any other business, for that matter. I remember, maybe a month of two into my time there, telling Joel that I'd studied English. He was a little taken aback, maybe surprised at himself for having hired a math-illiterate almost-teenager to act as his assistant publisher. I issued checks, and handled most of the business administration for the magazine, and, in my two years there, somehow managed not to burn the place down.

In These Times was a great place for me, as it has been for many other young journalists, to learn how a magazine works. It was also where I developed my own politics—a sort of second undergraduate education. I’m very grateful to the magazine, to Joel in particular for trusting me as he did, and to everyone else I worked with there. ITT attracts a smart, competent, and kind bunch.

A selection of In These Times ink stamps, used for fundraising mailings (ITT Archives)

Cole Stangler

Staff writer, 2013-2014

One of the basic hurdles for In These Times reporters is that many sources aren’t familiar with the magazine. As a full-time staffer, I’d regularly introduce myself and the publication over the phone. More often than not, people on the other end would respond with a question of their own: “The What Times?” they’d ask. Or, “The News Times?” To a surprising degree, I’d get “India Times?” And my favorite, “the New York Times?” Occasionally, I thought about letting that last one slide—just to see if it made a difference—but I invariably corrected my respondents each time. “In, space, These, space, Times,” I’d carefully enunciate.

When I was a senior in college and working on my first cover story for the magazine, I interviewed Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.), co-chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus. I showed up to his office in Capitol Hill on an early weekday morning. I was anxious, under-caffeinated and in accordance with my erstwhile undergraduate style, sported longish, slightly disheveled hair. After a brief introduction, I pulled out my backpack and struggled to find my voice recorder. “Where’d you say you were from again?” he asked as I fumbled around for far too long. “High Times?”

I accompanied Bernie Sanders on a fall 2013 road trip in the South that was, in retrospect, a clear trial run for the presidential campaign. Toward the end of my brief stay, it dawned on me that he might be preparing to run for president. Naturally, this was the last question I asked the senator during our interview and he replied in a way that clearly suggested he was mulling a White House bid. Back in D.C., I told friends I was absolutely positive he was going to run in 2016 and they laughed at me.

In any case, In These Times became one of the first media outlets to cover Sanders’ historic presidential campaign. I’m grateful the magazine thought it a good idea to send a 23-year-old reporter to Alabama and Georgia to cover a speaking tour organized by the junior senator from Vermont in a non-election year—and I’m glad the Sanders camp recognized In These Times as a publication worth giving access to.

Hand-edited copy for an early letters page (ITT Archives)

One of my favorite things about In These Times is its unapologetically critical coverage of organized labor. Too often, progressive publications practice self-censorship when confronted with some of the movement’s uglier elements—say, its racist or environmentally damaging tendencies. In These Times takes a very different approach: Editors understand the fear of airing our side’s “dirty laundry” doesn’t just translate into bad journalism—it’s actually counterproductive for the movement.

In May 2014, I teamed up with two other In These Times writers to report on the AFL-CIO building and construction trades department’s embrace of the fracking boom. The story critically examined the benefits of the trades’ newfound alliance with the nation’s top oil and gas lobby—and it highlighted a painful contradiction: The unions’ supposed “partner,” the American Petroleum Institute, was leading lobbying efforts against a rule that the Occupational Safety and Health Administration projected would directly save the lives of hundreds of workers each year—in construction, oil and gas and elsewhere. After we published the story, I sent it a building trades union official. I received a profanity-laden response that remains my favorite from any spokesperson to this day. He called out my journalism, my band, my masculinity—and ended his tirade like this:

There's a saying that goes, “An honest man's pillow is his peace of mind.” The men and women of North America's Building Trades Unions will sleep well tonight. I surely doubt that you will.

Clearly, we had hit a nerve. I knew it meant we did a good job.

Micah Uetricht

Intern, 2009-2010, associate editor, 2014-2016

In These Times changed my life. I came to the magazine as an intern, my only journalism experience at my school newspaper. I did the whole bit—fact-checking; transcriptions; sitting silently through editorial meetings, terrified I’d say something stupid.

Afterwards, I worked in the labor movement but kept contributing to the magazine. I saw it as a hobby: the real work was in unions, I thought to myself, but it was fun to see my name in print once in a while.

Over the years, I kept at that hobby, and it somehow became a job: associate editor at In These Times. Still, I figured I’d just do it for a little while before returning to the real action. Then something funny happened: I decided this was the action I wanted to be a part of.

Chicago’s 2015 mayoral elections sealed the deal. I was in the office late most nights for weeks, pounding out blog posts about Mayor Rahm Emanuel—his brand of Democratic union-busting and privatization, the unions that cheerfully lined up behind him.

Our coverage was uncompromising, occasionally scathing. It shifted the political conversation in the city (and won me a few enemies in labor). I felt the power of journalism to set the terms of a political debate—and to polarize it. (Even if my groundbreaking story about Mayor Emanuel tipping a cafe worker 37 cents on a $7 bill didn’t become the kind of marquee campaign issue that I thought it would.) Writing and reporting didn’t feel like a hobby anymore. It felt like a calling.

ITT’s 40-year history is a proud one, characterized by independence from and confrontation with the powerful—whether neoliberal Democrats, reactionary zealots or union hacks. I’m proud to have played a small part in that history. But I’m also deeply grateful I had the chance to let that history transform me.

Selections from this feature ran in the 40th anniversary issue of In These Times.

Selections from this feature ran in the 40th anniversary issue of In These Times.

photo by Steve Kagan (ITT Archives)

Want 40 more years of independent news and analysis? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: