How Trump’s Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric Has Heightened the Barriers to a Black-Brown Coalition

The ‘taking our jobs’ myth continues to sow division in Chicago’s working class communities.

August 30, 2017 | September Issue

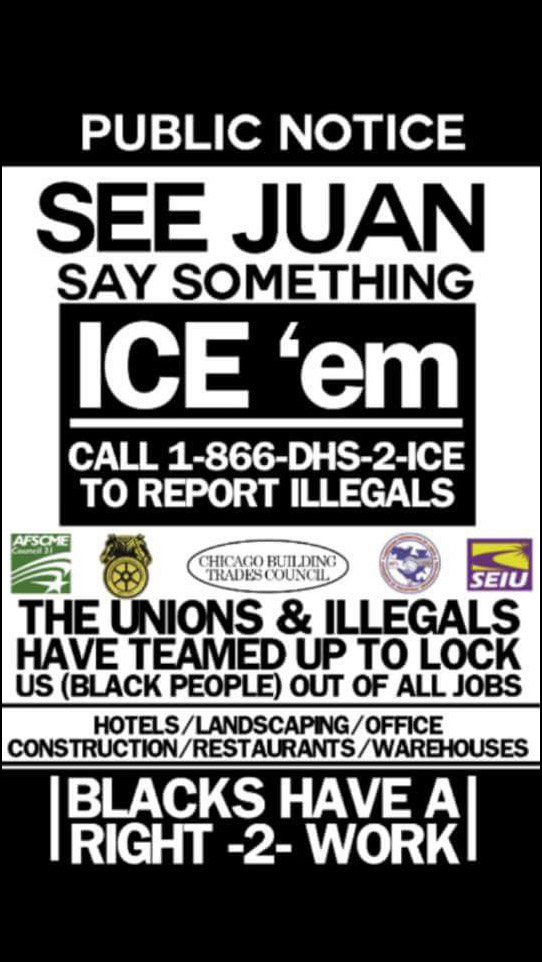

The online flyer is a mock-public notice. “SEE JUAN, SAY SOMETHING” jumps out in bold black letters, followed by “ICE ’em.” Below that is a number to call U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) “to report illegals.”

“The unions and illegals,” the flyer claims, “have teamed up to lock us (black people) out of all jobs.”

Mark Carter of Voices of the Ex-Offender, a group that advocates for formerly incarcerated African-American men, is known for his anti-immigrant rhetoric. The flyer isn’t his, but he’s happily posted it on Facebook.

Carter is a proud Donald Trump supporter. “A lot of things he talks about benefit the low- and very-low income black people,” he says. “We’ve been pushing ICE to come in and investigate these construction sites and do what needs to be done to stop this flow of illegal immigrants into this city and country.”

Carter lives in North Lawndale, a black neighborhood on Chicago’s West Side with high poverty and disinvestment. Neighboring South Lawndale is mostly Latino and boasts a thriving commercial district on 26th Street, with a panoply of small businesses. The stark contrast has no doubt molded Carter’s views.

“For low-income people, there is no black and brown relationship in this city—that’s why there’s a North Lawndale and South Lawndale,” Carter says.

Mark Carter, an advocate for black ex-offenders, supports Trump’s immigration agenda.

Chicago is one of the most segregated major cities in the nation. It’s also the second-most segregated along black-brown lines, after Detroit.

During the Great Migration a century ago, hundreds of thousands of black Southerners ventured to Chicago in search of a better life. Racist housing policies confined them to an area known as “the Black Belt,” setting the stage for ongoing segregation.

Thousands of Mexicans arrived in Chicago as low-wage laborers through the federal bracero program in the 1940s, many eventually settling on the city’s Near West Side. Subsequent waves of gentrification have forced Latino communities farther from the city’s center, but the population has grown steadily to about 790,000, or 29 percent of Chicago’s population.

Meanwhile, during the past three decades, black flight—driven in part by a lack of jobs and strong public schools—has reduced Chicago’s African-American population by more than a quarter, from about 1.2 million in 1980 to 850,000 today. The exodus of black families who could afford to leave triggered a vicious cycle, leaving black neighborhoods ever poorer and underpopulated. The median family income of black Chicagoans has declined since 1960 (from $37,121 to $36,720 in 2015), even as the median income for Latino families has risen (from $41,942 to $47,308).

When African Americans came to Chicago, whites accused them of stealing jobs. Now, some black Chicagoans have that attitude toward Latino immigrants.

George Blakemore is an older black man and political gadfly who shows up at various city agency meetings. He is serious about maximizing his allotted two minutes during the public comment period. At a June Chicago Housing Authority board meeting, Blakemore complained about “illegals.”

“Many illegals are working in these construction jobs,” he said. “They don’t even belong here. It’s the negative effect on the black community. My people were born here. Black people need a sanctuary city.” A smattering of black audience members cheered him on.

Chicago has been at the forefront of cities proudly proclaiming themselves “sanctuaries” and pledging to limit cooperation with federal immigration authorities. Carter, like Blakemore, chafes at the idea of sanctuary, arguing that low-wage undocumented laborers undermine black achievement.

Blakemore and Carter’s opposition is by no means mainstream. There’s a vocal local opposition to Trump’s immigration agenda, from City Hall to grassroots activists. Meanwhile, a number of social justice organizations, including Black Youth Project 100 (BYP100), Latino Policy Forum and Organized Communities Against Deportations, are seizing this moment to build coalitions between black and brown communities on likeminded issues. “We’re really working to tear down barriers to solidarity,” says Aislinn Pulley, 37, lead organizer for Black Lives Matter in Chicago.

But organizers like Pulley acknowledge that much work needs to be done to foster trust, combat xenophobia and reimagine a sanctuary city that’s safe for everyone.

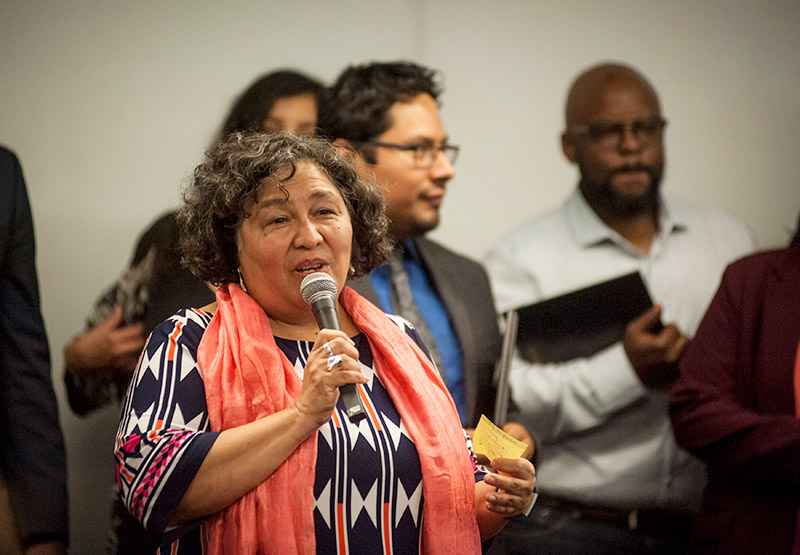

The Latino Policy Forum’s Sylvia Puente says the real issue is “how African-American and Latino communities continue to be exploited.”

The bigger picture, says Sylvia Puente, executive director of the Latino Policy Forum in Chicago, is that the United States criminalizes undocumented immigrants who provide low-wage labor but often does not penalize the employers who exploit that work—whether it is plucking birds at a chicken processing plant or pouring water at a restaurant. “We have an upper-class economy built on low-wage labor,” she says. “It’s unfortunate that a sector in the African-American community is now saying, ‘These people are taking our jobs.’ ”

Puente believes such arguments have little basis in fact. She points to a September 2016 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine that found the impact of immigration on wages and the labor market to be “very small.”

But the report contains a caveat: “To the extent that negative impacts occur, they are most likely to be found for prior immigrants or native-born workers who have not completed high school—who are often the closest substitutes for immigrant workers with low skills.”

In 2016, the graduation rate for black male students in Chicago public high schools was only 57 percent, far lower than any other group. And the job prospects for young black men in the city are slim. One report found that 47 percent of 20- to 24-year-old black men in Chicago are neither in school nor employed. Latinos in that bracket fared much better, with only 20 percent out of school and work (but still not as well as white men, at 10 percent).

“There’s no question” that discrimination plays a role in these statistics, says Christopher Williams of the Workers’ Law Office. His firm has brought three recent suits against Chicago temp agencies and the employers they serve, charging discrimination against black workers in favor of Latinos. Former dispatchers for the agencies testified that employers used racist codes, requesting feos (Latino laborers who will do “dirty” work) rather than guapos (“pretty boys,” referring to young black men).

Williams says Chicago’s low-wage factories and warehouses have shifted from full-time to temporary workers in a deliberate ploy to “avoid or evade labor laws” and keep costs down. Similarly, they prefer undocumented workers, who are seen as less likely to complain about violations.

Williams describes these jobs as “the bottom of the barrel”—work that can be obtained by those with a criminal record or without a high school degree. In other words, employment for the otherwise unemployable.

All of this might seem to prove Mark Carter’s point.

But Puente believes it’s a mistake for low-income workers to fight for scraps. The real issue, she says, is “how African-American and Latino communities continue to be exploited.”

White communities in Chicago receive far more investment than their black and Latino counterparts. For example, a WBEZ analysis found that under Mayor Rahm Emanuel, three-quarters of $650 million invested in public school expansion went to disproportionately white schools, even though Latino students are most likely to be affected by overcrowding. And the city has invested twice as much in TIF funds—money earmarked for job creation and development in poor neighborhoods—in white Chicago neighborhoods as in black or Latino ones.

South Side activist L. Anton Seals Jr. scratches his head over why a majority black-and-brown city allows a white chokehold on political power. The City Council is majority non-white, but it has served as a rubber stamp for a procession of white mayors who divert the city’s resources to white constituents. In theory, a black-brown electoral alliance could transform the city.

At moments, that has seemed possible. A multiracial alliance elected Chicago’s first black mayor, Harold Washington, in 1983. He launched a commission on Latino affairs and, before his death at the start of his second term, placed Latinos in positions of power in City Hall. But by 2015, when Jesus “Chuy” Garcia ran for mayor, he didn’t get the black turnout needed to defeat Emanuel in a runoff. Fifty-seven percent of voters in majority-black wards went for Emanuel.

Seals says that black-brown solidarity is undermined by “this notion of one group being the subgroup under the white people: ‘Who gets the resources to be closer to the king?’ ”

“I am not mad at any Latinos at all,” says radio host Maze Jackson. “[But] my first priority is black folk.”

“My first priority is black folk,” says Maze Jackson, political strategist and flame-throwing host of the morning drive show on WVON, a long-standing black AM talk-radio station. He uses his bully pulpit to rant against the concept of a sanctuary city.

But he first makes a disclaimer.

“People like to characterize me as anti-Latino,” Jackson says. “I’m not. I really have some great relationships with Latinos.”

Jackson assures me of this repeatedly in person. We meet in the back office of a black-owned barbershop in the historic black neighborhood of Bronzeville, on the South Side. This is where Jackson likes to have his serious meetings or interviews. He’s donned camouflage pants and a tan T-shirt with a zinger of a hashtag he coined: #WIIFTBP, or, “What’s In It For The Black People.”

“The liberal white agenda would have black people bury how we feel,” he says. “I could be for a sanctuary city if you show me the benefit for black people.”

Jackson says black folk compete with Latinos for low-skill, low-wage jobs, whether in fast food, grass cutting or as hotel valets. He asks: How can the mayor be on TV promoting undocumented children going to college, while closing public schools?

“I am not mad at any Latinos at all,” Jackson says. “But I’m in a competition for resources. Latinos have become the preferred minority in Illinois. As they look to assert their power, they aren’t looking to take from white folk, but from black folk.”

University of Illinois-Chicago historian Barbara Ransby says those who hold such sentiments are falling prey to “the oldest trick in the book.”

As opposed to looking for where the wealth ends up—which is not in poor Latino communities—people fall into a divide-and-conquer trap, she says. “It’s an effective tool to undermine coalition efforts at collective resistance. But what I’m seeing is greater and greater collaboration.”

Anthony Stewart of Black Workers Matter sees “a lot of similarities” in employers’ mistreatment of black and Latino workers.

There’s a flip side to the anti-immigrant bombastic talk from Mark Carter.

Latino immigrants arrive here with racial baggage and swallow up stereotypes about black Americans, says Adriana Díaz, who works with a public land trust in Chicago. “Conversations about our own anti-blackness are difficult, but we have to have them in order to build trust with other communities,” she says.

Diaz was one of 24 fellows—all African Americans or Latinos engaged in public sector or social justice work—brought together by the Latino Policy Forum to bridge black-brown divides. They had tough conversations about stereotypes like “Mexicans are taking our jobs” and explored the erasure of black and indigenous roots on both sides of the aisle. In the process, they formed bonds.

“We just got to know each other,” says Analía Rodríguez, executive director of Latino Union of Chicago. “Now some of us are continuing the work.”

Elsewhere in the city, other multiracial collaborations are afoot. On a warm weekday June morning, hundreds of people—black, white, Latino—gather across the street from City Hall. They are here for a rally: Defy Trump, Defend Sanctuary for All. Their signs read, “One Welcoming City for All.”

In the months since Trump moved into the White House, the meaning of “sanctuary city” has expanded. Police violence, activists argue, is just as much a threat to the safety of black and Latino youth as ICE raids are to undocumented immigrants. And a lack of housing, healthcare or schools is antithetical to community safety.

Activists are fighting to close loopholes in the city’s Welcoming City ordinance, which restricts local authorities’ cooperation with federal immigration authorities. One such loophole allows police to hand over anyone in the city’s controversial gang database to immigration officials.

“There’s rampant labeling of black and brown residents as alleged gang members and affiliates with no accountability, due process or way to challenge the accuracy,” says Janaé Bonsu of BYP100.

Berto Aguayo, 22, a Southwest Side community organizer, sees the gang database as a natural issue for black-brown coalition-building. “Both communities want to know who gets on this list and make sure no one is profiled,” he says.

Asked what he thinks of the efforts to expand sanctuary, Maze Jackson says, “I think they are finding out their views are not aligned with most of the black community. They need a face save.”

On June 15, Black Workers Matter and Ferrara Candy Company workers protest alleged collusion between Ferrara and the Chicago suburb of Forest Park to opt out of the county’s $10/hour wage ordinance.

“It’s been shocking to me how many of my African-American clients voted for Trump—solely on the basis of immigration,” says Christopher Williams of the Workers’ Law Office. “When I talk to one of my clients, their stories are always the same. They go into a temp agency in the morning. The room starts out about two-thirds Latino, one-third black. By the end of the morning, when the assignments have been made, it’s 100 percent African-American.”

The perception, then, is that the mostly Latino dispatchers are discriminating against black job-seekers. “But it’s the companies,” Williams says. In fact, “the dispatchers didn’t like what they were told to do.”

Williams believes there are plenty of jobs to go around. “[Dispatchers are] having difficulty filling orders because they get complaints when they send black workers,” he says.

Latino dispatchers’ testimony was critical to the success of a class-action discrimination suit filed by black workers against Ferrara Candy Company and two temp agencies. The companies denied wrongdoing, but settled for $1.5 million in 2015. Black workers tell Williams that temp agencies are now giving them more assignments.

One of the Ferrara workers, Anthony Stewart, says that when he sat down and talked with Latino workers, the two sides stopped falsely blaming each other and realized the candy company’s role.

“They wanted to create a hostile environment by segregating the black and Latino workers,” Stewart says. “Telling the blacks the Latinos are taking their jobs and telling the Latinos the blacks are taking their jobs. It’s not true. We had to talk to people and hear their stories. You see there are a lot of similarities. It gets easier.”

In 2016, Stewart helped organize Black Workers Matter to fight anti-black workplace discrimination. Now they are doing something to mutually serve black and Latino workers—advocating for a higher minimum wage.

At a rally this spring, Black Workers Matter members held signs in English and Spanish that read, “Fight for 15 - Lucha por 15.”

Above: On June 15, Black Workers Matter and Ferrara Candy Company workers protest alleged collusion between Ferrara and the Chicago suburb of Forest Park to opt out of the county’s $10/hour wage ordinance.

is a reporter for WBEZ Chicago. She is the author of several books, most recently The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation.

Want more independent news and analysis? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: