Kentucky's lifeblood is drying up.

May 23, 2016

For nearly a century, Harlan County, K.Y., has occupied an outsized place in the American consciousness. Coal is the lifeblood of Harlan, where miners’ fierce battles against deadly working conditions remain a symbol of union grit and militance. But Harlan is also an emblem of the hard times that have fallen on coal country.

Coal mining once provided a middle-class living. Mine workers in Harlan won living wages and benefits following a series of strikes and violent clashes with scabs and mine owners in the 1930s that earned the county the nickname “Bloody Harlan.”

Miners charted a risky path to economic security. Collapses, explosions and other accidents killed tens of thousands during the 20th century. Many who survived were still killed by coal, albeit more slowly.

Lifelong Harlan County resident Priscilla Stephens, 66, recalls the death of her father, Charlie Simpson, from black lung disease in 1966. Simpson spent 37 years in the mines to support his wife and 14 children. “It cost him his lungs and his life,” says Stephens. “Sometimes he would cough and keep coughing, and it was just black-looking, like that old coal dust.”

With “King Coal” now on its deathbed, residents wonder what will come next. On an overcast Friday in mid-March, Levi Burkhart watches from his hilltop home in Coldiron, Ky., as a stream of coal trucks rumbles by.

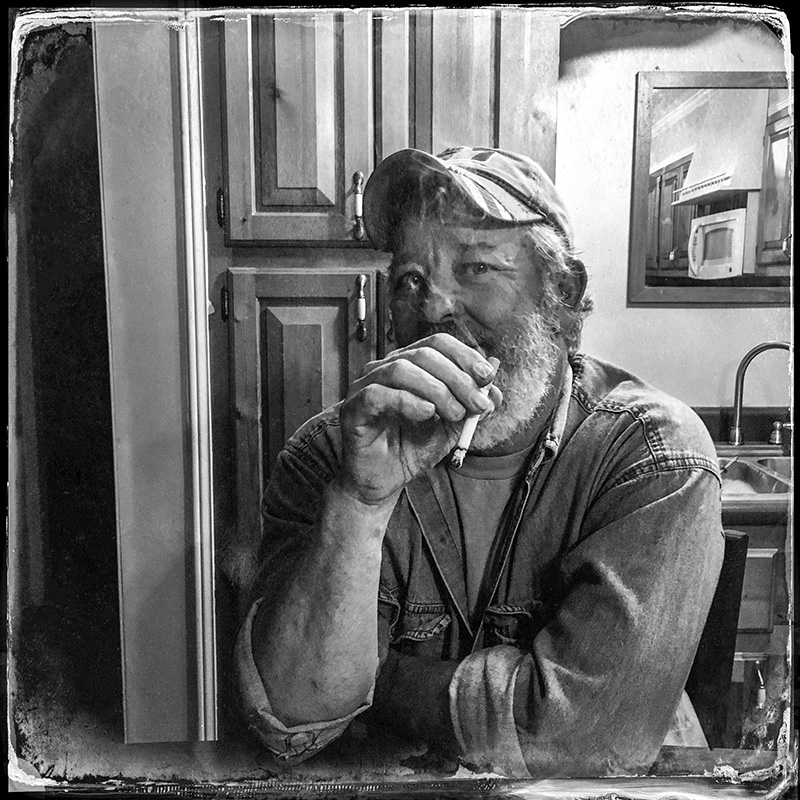

“If you look at it from the road, you’d think it was booming,” says Burkhart, 56, a former coal tipple operator who has also developed black lung.

Those appearances are deceiving. The coal industry has been in decline for the past eight years, a development that many blame on Obama’s “war on coal” and the EPA’s tightening of environmental standards. “Obama shut down the mines,” former miner Robert Simpson, 58, says flatly.Environmental groups say other factors, such as the abundance of cheap natural gas, are behind coal’s slump. And jobs in the industry have been vanishing since the 1980s, thanks to mechanization. Eastern Kentucky has been especially hard-hit: The number of miners employed in Harlan County fell from more than 3,000 in 1988 to fewer than 1,000 in 2014. No unionized mines remain in the state.

Whatever the reason, new industry has been painfully slow to materialize. Priscilla Stephens ticks off a list of companies that have come and gone: a furniture factory, a long-time furniture store, a sock factory.

“About everything is moving,” she says. “All we’ve got down here is grocery stores and restaurants.”

This presents young people with a hard choice. Many end up leaving families behind to seek factory work in cities or mining jobs in southern Illinois or Alabama.

“The community is not only suffering,” says Chester Napier, 75, a former mining company driver. “It’s dying.”

Robert Simpson, 58, mined for about a dozen years in the 1980s and 1990s before becoming a carpenter. Four generations of Robert’s family have worked in the mines, including his grandfather, Charlie Simpson, his father, Bobby Simpson (p. 28) and his son-in-law, Danny Stewart (p. 28). Robert and his wife, Judy, live on a plot of land off Route 568 in the tiny town of Cranks. Their daughter, Cherish, lives at the front of the property; their other three children, two of whom are from Robert’s first marriage, live elsewhere in Harlan County and in Richmond. Work is often erratic for Robert, but he recently found three months’ work building a home. “Things are good for the moment,” says Judy, 52, who recently moved from part- to full-time status at Walmart.

Bobby Doyle Rowlett—named after his grandfather, Bobby Simpson—left Harlan County in 2015 for a position with the RJ Corman Railroad Group. He traveled as far as the Canadian border and worked as many as 12 days in a row. On breaks, he came home to see his fiancée, Lauren Blair.

Sitting on a couch in his grandfather’s home, Rowlett explained that he had been willing to pay the physical price of working in the mines in order to be close to home. Blair talked him out of it.

“I said [the work] would be gone in a year, and I was right,” Blair said. Things are looking up for the couple. Rowlett moved back after securing a coveted position at the railroad company less than an hour away. He and Blair plan to marry in June. Most residents haven’t been so lucky. Some, like Danny Stewart, an unemployed fifth-generation miner, are placing their hopes in a Donald Trump presidency to revive the moribund coal industry. Others, like Bobby Simpson, draw on religious faith and a ceaseless work ethic to keep going.

All agree on the region’s bleak present and dim future.

“It’s not good,” says Napier. “Some of the politicians say they’ll bring the coal back, but the coal will never be back.”

Bobby Simpson, 79, has been blind for more than a half-century, but still managed to shovel coal. Bobby’s wife, Becky, who died in 2013, was a lifelong advocate for the people of Harlan County. In April 1977, she watched from nearby mountains as floods caused by strip mining washed away everything her family owned. The couple later founded the Cranks Creek Survival Center, a nonprofit that provided food, clothing and home repairs to area residents for decades. Hundreds of volunteers came each year to fix porches, hang dry wall and mend roofs. Bobby has continued the work since Becky’s death, but the number of volunteers (like those photographed here with Bobby) has dwindled. “We don’t have no money to pay nothing with,” Bobby says. “I’ve been trying to keep it going, but when you don’t draw much, it don’t go far.”

Danny Stewart, 30, is a fifth-generation miner who began working in the industry shortly after graduating from high school in 2004. The pay was good, and he was able to find work easily in one mine or another. But since the 2012 election, he says, work has been uneven at best. It’s been months since he’s had a job. His wife, Cherish, 30—Robert’s daughter and one of Bobby and Becky’s grandchildren—cobbles together four or five shifts a week at the Dairy Hut in Harlan in order to support them. Danny cares for his 7-year-old son, Aiden, and occasionally hunts ginseng on the nearby mountains to sell for a few dollars per pound.

“We’re just barely getting by on that,” he says.

Many of his friends have faced similar challenges and left the area, but Danny says he has no plans to move because he has a lot of family nearby. And while he’s open to working in other industries, jobs anywhere are in short supply.

“I thought about trying to find something else, but there ain’t much stuff around here to do,” he says.

Although Stewart says he’s not much for politics, he harbors hope that November’s presidential election will bring Donald Trump to the White House and mark a change for him and his family.

“I’d like to see the next president ... go in on coal,” he says.

Chester Napier grew up in the 1940s in a one-room log house in the woods of Smith, Ky. As a boy, he learned to hunt squirrel, groundhog and deer from his father, Fred Napier. The family of eight children had little money, but Chester was happy and didn’t think of himself as poor. Later, he considered his family fortunate because neither he nor his seven siblings died from the cold that engulfed the house. “When you get up in the morning and you got to take a hammer to make a hole in the water bucket to get you a drink of water, now that ain’t no good old days,” he says. “A lot of kids froze to death right in the house.” Following a conflict with his father in 1959, Chester moved to Chicago, where his two older brothers and one of his sisters lived.

Thousands of others from Appalachia made the same migration. Chester found work in a gear factory, but home beckoned a dozen years later when one of his children died just three days after being born. Chester had done so well that the company owner tried to entice him to stay with a raise of $1 per hour, from $6.75 to $7.75. He was unmoved. “I ain’t been back,” he says of Chicago. “I don’t intend on going back.” He’s lived in Harlan County ever since. Now 75, Chester has endured his share of losses. In the 1970s, a strip-mining company asserted its ownership over the mineral rights for property he owned and forced him to sell the land. His wife, Annie, died about a decade ago. The battery in Chester’s pacemaker has three years left. When it runs down, he says he’ll decide whether he wants to have a new one installed. He doesn’t want to have to depend on anyone.

Whenever it is that death comes for him, Chester knows where he will be. “I’m home where I want to die at, in these mountains here,” he says.

Each month, millions of tons of coal are excavated from the seams of the Appalachian Mountains. Much of the landscape now bears the scars of mountaintop removal mining, a last-gasp effort by coal companies to revive the industry. In his 2016 State of the Union address, President Obama called for new investment in communities reliant on fossil fuels. “We do them no favor when we don’t show them where the trends are going,” he said.

Last year, his administration announced $14.5 million in federal grants for job retraining and other initiatives to help displaced coal and power industry workers.

Meanwhile, coal continues to fade from the energy landscape. The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that natural gas will replace it as the nation’s primary source of electricity in 2016.