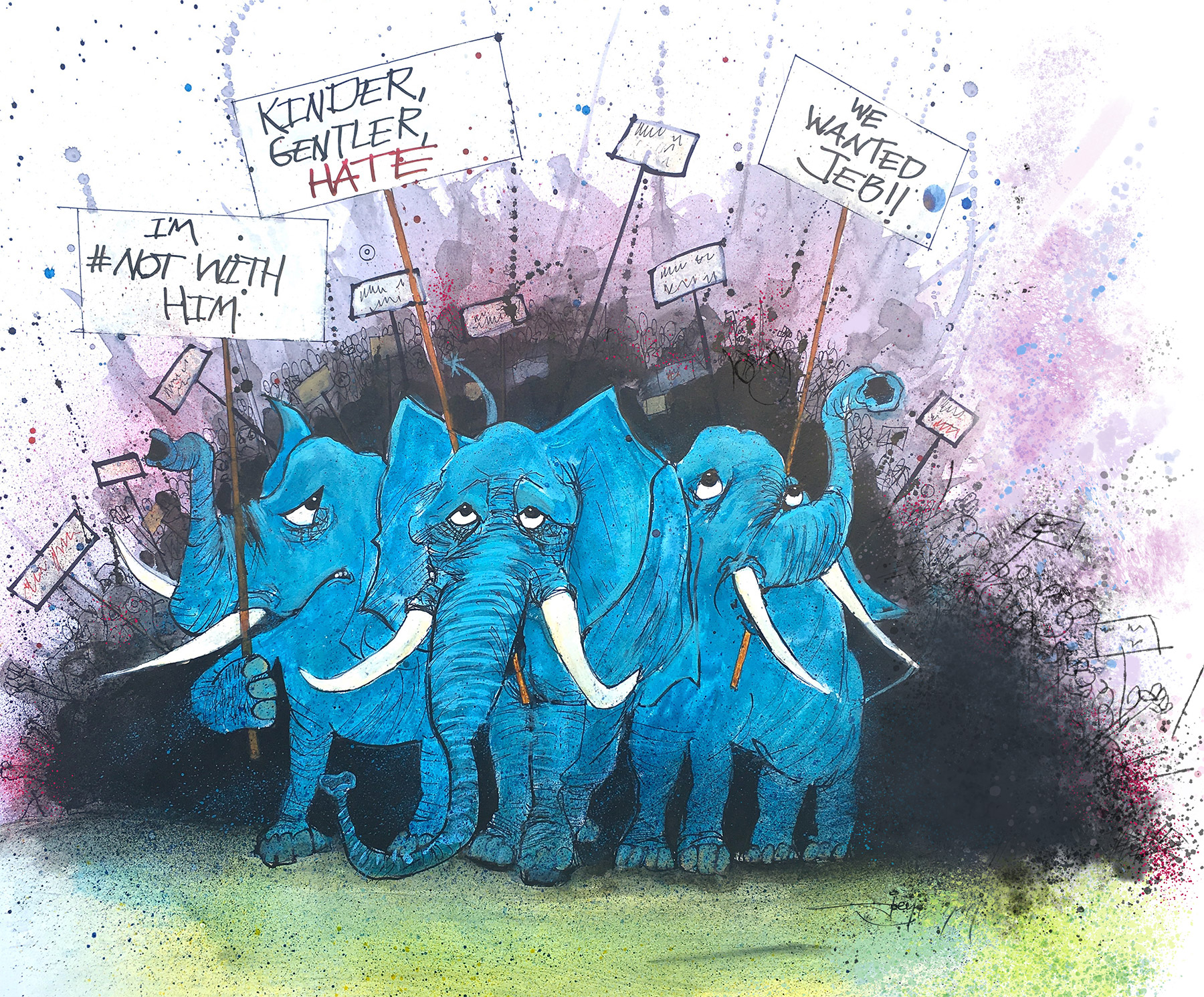

The Elephants in the Resistance:

Don’t Trust the Anti-Trump Republicans

Sen. Jeff Flake and his ilk aren’t the heroes we’re looking for.

November 14, 2017 | December Issue

In a party that shamefully prostrated itself before Donald Trump, the junior senator from Arizona has stood out as a consistent voice against him. Jeff Flake was even an occasional voice of Republican sanity before Trump’s emergence—for example, crusading against the Cuban travel ban. On October 24, he won fans even among liberals by announcing he was quitting the Senate, giving a speech that accused his colleagues of normalizing “the daily sundering of our country” in ways that have “nothing whatsoever to do with the fortunes of the people that we have all been elected to serve.”

That same day, Flake went on to vote for a Trump-supported measure preventing the people he had been elected to serve from being able to sue financial institutions that defraud them.

How do you solve a problem like Jeff Flake? Some would accept anti-Trump conservatives as a valuable part of the resistance. As Bloomberg columnist Jonathan Bernstein puts it, they show “how broad the coalition against the president is.”

Others maintain that these Republican critics of Trump represent a paradoxical danger: A Republican Party that follows their lead and gets rid of Donald Trump would surely be celebrated in the mainstream media as washed in the blood of the lamb—even though it would remain just as evil as before. It would still include, for example, Jeff Flake, who has voted in line with Trump 90 percent of the time.

Flake isn’t the only Republican winning centrist and liberal hearts. This summer, word in Washington was that people around the popular Democratic governor of Colorado, John Hickenlooper, were floating trial balloons for a 2020 bipartisan presidential run with Gov. John Kasich of Ohio—a lustfully privatizing and union-busting Republican who has jammed through some of the most invasive abortion restrictions in the country and a law allowing guns in bars.

Then, this fall, Sen. Bob Corker (R-Tenn.) was feted by the likes of historian Douglas Brinkley as a “real leader” after he called the White House an “adult day care center” bringing us to the verge of “World War III.” This Tennessee hero, however, also wants to gut Medicare and Social Security, disbelieves human-made climate change and stubbornly defended the war in Iraq.

Then came, of all people, George W. Bush, who once upon a time added torture to America’s military arsenal—but in an October speech complained some nameless you-know-who in Washington has introduced “bullying and prejudice in our national life.”

But then again, it’s a bald fact that Trump is bringing us to the brink of World War III, so maybe we need all the help we can get to be rid of him. So when two new anti-Trump jeremiads from prominent conservatives—one of them by Flake—recently appeared on shelves, one might have approached them with a desperate sort of hope. Maybe, just maybe, they might demonstrate a path to a broader enlightenment—a recognition that the deformities some Republicans now observe in their president were not born yesterday, but have long been baked into the conservative cake.

Flake, or whatever robot it is that writes books “by” senators, put his objections to his party’s surrender to Trump between covers earlier this year. He borrows his title from Barry Goldwater’s 1960 manifesto, The Conscience of a Conservative. “As conservative principle retreated,” he argues, “something new and troubling took its place.”

Its lineaments, he says, are “nationalism, populism, xenophobia, extreme partisanship, even celebrity.” Reading that, liberals might find their heads swiveling like Linda Blair’s in The Exorcist. When, precisely, has American conservatism been bereft of nationalism, populism, xenophobia and extreme partisanship, let alone (in its deification of a certain former movie star) celebrity? Other supposed heresies include rejecting conservatives’ “ardent belief in free trade” (but for most of the first half of the 20th century, non-Dixie conservatives were protectionist), and “realpolitik federal budgeting” (he must have missed the day Dick Cheney explained, “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter”). Flake’s bad history goes on from there.

Conservatism is an ideology that, at its essence, is about reasserting hierarchy and authority against the liberatory energies of the subaltern classes. The methods and means, however, vary greatly across time and space. In late 19th-century Germany, for instance, Otto von Bismarck established a system of social insurance to cement workers’ loyalty to German empire; that was conservatism. In the 1920s, in the United States, many Ku Klux Klan leaders supported universal government-provided healthcare as a way to protect Nordics from diseased immigrant hordes; that was conservatism. The more Goldwaterite version Jeff Flake reifies as conservatism tout court is, like all conservatisms, a contingency born of a particular time and place. Because in both style and substance the original Conscience of a Conservative remains the best short introduction, we might label it “conscientious conservatism.”

Conscientious conservatism is policy-centered, aimed at end runs around the liberal state that the New Deal created. (Goldwater’s book, for example, proposed replacing the graduated income tax with a flat tax for all earners, and “a 10 percent spending reduction each year in all of the fields in which federal participation is undesirable.”) It fetishizes something it calls “freedom” (which is only ever traduced by the state, never private employers), and also “principle,” which for Goldwater meant proposing things that during his own time bore little chance of enactment (like ending all farm subsidies). For Flake, it involves staging the occasional act of spectacular, if limited, political self-immolation. For instance, lovingly recounted here, the time he went after an earmark (for a local highway interchange) beloved of one of the most powerful members of his party, then-House Speaker Denny Hastert (R-Ill.).

The natural home of conscientious conservatism—which has always existed uncomfortably alongside its embarrassing, ill-bred populist cousin—is the think tank. One role of the conservative think tank within the right-wing firmament—like the one Flake once ran, Phoenix’s Goldwater Institute—is to present conservatism’s “respectable,” “principled” and “intellectual” face. As a cherished instance of the Empyrean heights from which he believes conservatism has fallen, Flake describes a beloved keepsake: “a T-shirt from the early 1990s, commemorating the barnstorming battle royale national tour taken by two Texas Republican congressmen—Dick Armey and Bill Archer—selling out lecture halls to debate the benefits of a national flat tax versus a national consumption tax.” Thus his cri de coeur: “We desperately need to get back to the rigorous and fact-based arguments that made us conservatives in the first place”—not today’s “race to the bottom to see who can be meaner and madder and crazier. It is not enough to be conservative anymore. You have to be vicious.”

Well and good, and kudos to him for that recognition. The problem this book reveals, however, is just how crazy, vicious and non-fact-based conservatism remains even at its most “conscientious.” What else is a debate between a flat tax and a consumption tax, after all, than a contest between different methods of starving the state at the expense of the poor? Or consider his critique of current Republican immigration policy. He prefers the days “when crossing the border could be done frequently and easily”—because then, “the workers didn’t tend to bring their families, because they didn’t intend to stay.” It was better, in other words, when Mexicans kept their heads down as cheap, interchangeable units of labor power. Those were the days!

It is a testament to the moral unseriousness of a Jeff Flake that the most serious idiocies, abuses of power, and viciousness of George W. Bush are here neither mentioned nor condemned. Naturally: As a congressman, Flake voted for most of them. “Presidential power should be questioned, continually,” he writes. “I’m from the West. Questioning power is what we do.”

Starting, I suppose, on January 20, 2017.

Then there is the story he tells to establish his bona fides as a hearty man of the American West, where questioning power is just what they do. He lost the tip of his finger to the 14-foot blade of an agricultural implement. “My dad wrapped my bloody hand tightly in his handkerchief, put me up in the truck and finished the job before taking me to the only doctor in town to get it seen to. … The battle scar didn’t keep me from doing my chores.” He was 5 years old.

No less than for Donald J. Trump, for Flake, “love” means passing on a vision of the world where authority is unquestioned and sadism is just part of the deal.

And “freedom” means—well, what? The town Flake was born in was named after his great-grandfather, who had been ordered by Brigham Young to settle there. Then, the better to commandeer state government, half the town was ordered to sign up as Democrats, the other half as Republicans. Flake finds this stratagem delightful. Then without irony, not many sentences later, he writes, “Politics is the art of persuasion. You’ve got to persuade people; you cannot compel them.”

It’s true, of course, that politics is the art of persuasion. As practiced by modern conservatism, however, the persuasion is underwritten by a con. The policies favored by “conscientious” conservatives have never been popular. Goldwater, after all, won only 38 percent of the popular vote in 1964. Flake, experts on Arizona politics inform me, owes his power largely to the fact that he is Mormon royalty in a state with an enormous concentration of politically active Mormons. What wins elections for conservatives has never been libertarian policy—certainly not in 1984, when Reagan won 60 percent of the votes while only 35 percent told pollsters they wished to see cuts in social programs. It is the role played by the ill-mannered stuff, the things Flake here derides as “nationalism, populism, xenophobia, extreme partisanship, even celebrity,” that puts conservatives in office.

At regular intervals, when the cruder members of the coalition begin getting too uppity in demanding their own place in the sun, angry volumes issue forth from members of Team “Conscientious” who feel victimized by the importunity. There was, in 1981, Thunder on the Right: The “New Right” and the Politics of Resentment by Alan Crawford, which went after uglies in the coalition that produced Reagan. Dead Right, published by David Frum in 1994, tore after Pat Buchanan. Victor Gold’s Invasion of the Party Snatchers, from 2007, flayed the “holy rollers” and “Neo-cons” behind the political successes of George W. Bush. It is a testament to the intellectual deficits of conservative intellectuals that each new iteration acts as if this time is the first that this tension has come to a head—and with no grasp that without their ill-mannered populist cousins, conservatives could never win elections at all. Usually, in fact, they say conservatives lose elections when they cease being conscientious enough.

It’s a pickle, for sure—and that makes Charlie Sykes an interesting case: For a nanosecond in the middle of his new book, How the Right Lost Its Mind, Sykes begins to grapple with this dilemma, almost. “The reality that many conservatives have been unwilling to face is that despite their insistence that America was a center-right country, there has never been a strong constituency for the kind of tough budget cuts that would either limit the size of government or reduce the national debt.”

Then it’s gone, and Sykes is back to hawking his preferred explanation for the Right’s recent ugly turn: It’s the Left’s fault.

Sykes won the contract to write this slapdash book on the strength of a genuinely interesting December 2016 New York Times op-ed announcing his retirement as a right-wing talk radio host, partly in shame at his own medium’s role in “delegitimizing the media altogether.”

The problem, for those who know Wisconsin politics, is that Sykes was not just a radio host but a sort of right-wing political boss—a think-tank impresario at the center of the ugly political culture that has characterized the reign of Gov. Scott Walker, whose political survival Sykes takes some proud credit for in the book. This fall, the darkest corners of that political culture were held up to the light during Supreme Court oral arguments about how Republican operatives, working in secret in a Milwaukee law office, gerrymandered legislative maps to give Republicans 60.6 percent of the seats in the Wisconsin Assembly with only 48.6 percent of the vote. A Democratic victim said it reminded him of an “episode of The Sopranos.”

While this was going on, without any criticism from Sykes, he carried out his own role within this culture, as a conveyor belt for arguments that Democrats only held on to power thanks to hordes of fraudulent black voters, who only ended up in the Dairy State in the first place because Milwaukee was, he claimed, a notorious “welfare magnet.”

His thesis is that the 2016 election “marked not only a rejection of the Reagan legacy, but also the abandonment of respect for gradualism, civility, expertise, intelligence and prudence—the values that once were taken for granted among conservatives.” The book provides a reasonable canvass of some of the more objectionable qualities of the alt-right, the poisonous mediascape epitomized by Alex Jones and Breitbart, and the vicious racism of Trump’s constituency—with barely any acknowledgment of how the preexisting conservative political culture in which Sykes was a not inconsiderable figure helped lead to these phenomena.

By Sykes’ heroes shall you know him. Not just Scott Walker, but the noted gradualist William Kristol—author of the infamous 1993 memo demanding no compromise with attempts to provide health security for Americans, lest Republicans “revive the reputation” of the opposition party. The ever-civil Jonah Goldberg—who “argued” at book length in Liberal Fascism that fascism, an ideology defined by its eliminationist hostility to liberalism, was another name for liberalism. Stephen Hayes—best known for his expertise in arguing that Saddam Hussein was responsible for 9/11. Erick Erickson, who, before he took on Donald Trump, prudently went after the National Rifle Association for being “a weak little girl of an organization.”

Oh, and Paul Ryan. “Whatever you might think of his policies, Paul Ryan is inarguably the most formidable intellectual leader the Republican Party has had in decades,” Sykes writes. When I read that, I couldn’t help thinking of the time Ezra Klein scoured Ryan’s 2012 convention speech to find something in it that was true, and found only two claims that were even “arguably true.”

Those are the good guys. The bad guys, besides Trump and his close associates, are you and me. “The excesses on the Left,” he argues, “pushed many small-government conservatives into an unnatural alliance with the authoritarian and nationalist right.” It is the “excesses on the Left,” I suppose, that impelled Paul Ryan to advance Donald Trump’s policy agenda all down the line.

Ryan made his bet that Trump’s populism could help him jam through unpopular policies. Which shows Ryan understands conservatism better than Charlie Sykes or Senator Flake: He knows the Right’s wonks and weirdos comprise a unified system. Show me an anti-Trump conservative who both understands this, understands their implication in it and is willing to articulate a thoroughgoing rejection of the whole package—and then, maybe, I’ll welcome them to my side. I haven’t found one yet.

is national correspondent for The Washington Spectator and the author of The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan.

Want to stay up to date with the latest political news and commentary? Subscribe to the free In These Times weekly newsletter: