I Saw the Good, Bad and Ugly of Donald Trump Supporters at His Chicago Rally

Not all Trump supporters in Chicago on Friday were racist. But some definitely were.

Branko Marcetic

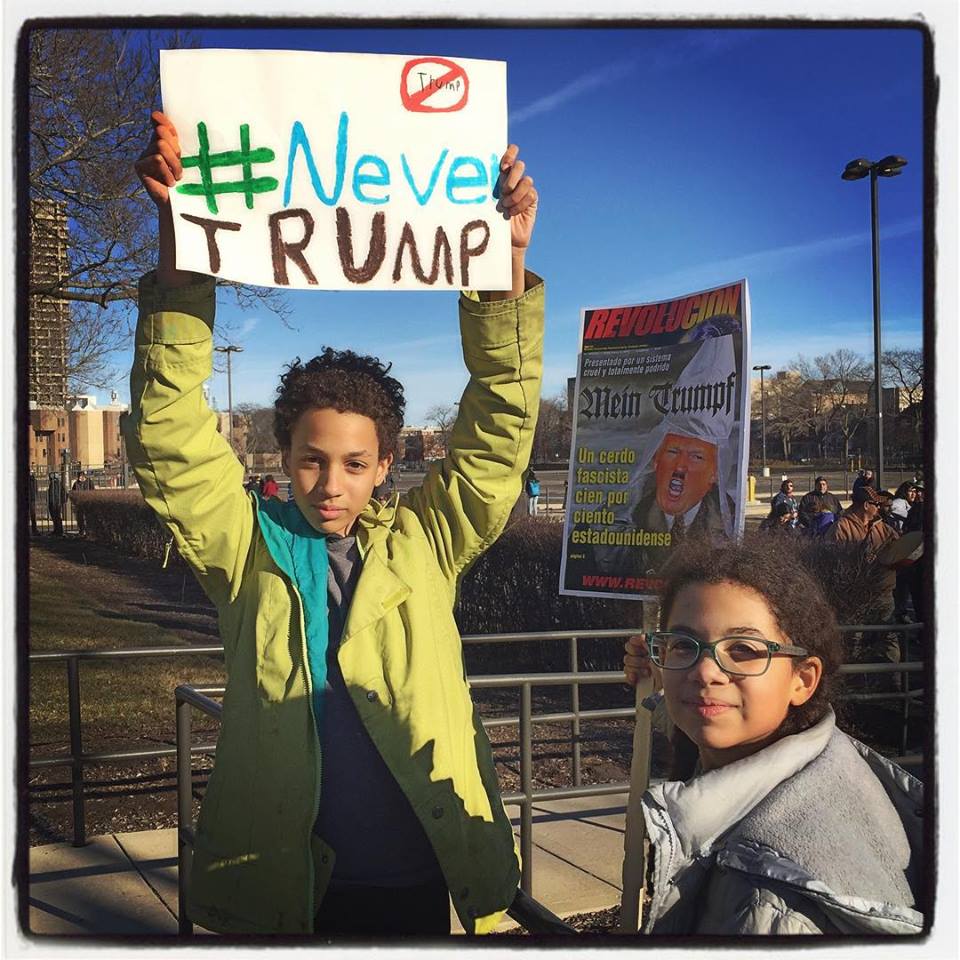

Before any punches were thrown at Donald Trump’s cancelled March 11 rally in Chicago, it was clear there was something in the air. It wasn’t just the large crowd of vocal protesters assembled behind a barrier holding up signs like “Dump the racist rapist!” and “Trump has baby hands,” or the row of police on horseback standing between them and the entrance to the University of Illinois-Chicago Pavilion. It was also the mind-bogglingly long line of attendees eager to see Trump speak, a full 10 minutes’ walk’s length, stretching all the way around the venue and back to the entrance like a snake devouring its own tail — a fitting metaphor for the conservative movement in the age of Trump.

Of course, it soon became clear that at least part of the reason for the huge attendance was the large number of anti-Trump protesters who had made it their mission to disrupt the event over what they saw as the GOP frontrunner’s racist and increasingly violent campaign. Although exact figures are impossible to confirm, those who had made it inside estimated that anywhere between half and three-quarters of the attendees were protesters.

The utter chaos that resulted has already been well-covered. People on both sides ripped signs from each other’s hands. Protesters spilled over the railing, with one activist jumping on stage and tearing up a speech left on the podium. A police officer pinned a CBS reporter to the ground with his boot. Trump supporters and protesters alike were escorted out by security, while brawls broke out across the pavilion floor. Trump’s press officer announced to the crowd that the event was cancelled, and protesters cheered and chanted “Bernie!” and “We stopped Trump!”

A Trump protester wearing a sombrero and the Mexican flag outside of the UIC pavilion. (Meg Handler)

It’s difficult to say exactly how the violence began, though given the circumstances, it was perhaps inevitable. The determination of protesters to “shut down” the rally, coupled with the increasingly frequent instances of violence committed by Trump supporters and the steadily ramping-up of violent rhetoric by Trump himself, who has wasted no opportunity to egg on his more aggressive supporters, created a charged atmosphere inside the venue that was waiting for something to set it off.

The scene was markedly different outside. While there was the occasional spat — including a 50-foot shouting match between a Bernie Sanders supporter and man yelling that Stalin had “killed millions” — pro- and anti-Trump attendees mostly co-existed peacefully. When a protester walked past the line singing, “Take a dump on racist Trump,” Trump supporters laughed and went on with their lives.

This all changed inside the venue. There could be any number of explanations for this: the close proximity of protesters and Trump supporters, who were squeezed shoulder to shoulder with no escape; the science of crowd psychology; the potentially different make-up of the gathering inside (as anyone who got into the event had to come hours early, the attendees inside may have been among the real estate mogul’s more hardcore supporters).

The resulting violence, combined with similar (though by no means as intense) clashes at Trump rallies in Ohio and Kansas City over the weekend, plus a widely circulated photo of a Trump supporter making a Nazi salute at the rally, has led many to definitively declare the Trump-for-president movement as an example of thuggish fascism, American-style. But speaking with Trump supporters at the rally shows why it would be mistaken — even perilous — to reduce Trump’s support to this simple narrative.

“I’m suspicious of all the plutocrats”

For many months now, poll after poll has shown the breadth of support Trump has built over the course of his campaign — a fact the candidate himself relishes pointing out.

“We won the evangelicals. We won with young. We won with old. We won with highly educated. We won with poorly educated, I love the poorly educated,” he told an adoring crowd in Nevada upon winning the primary there last month.

This diverse (albeit largely white) coalition was on full display at the Trump rally on Friday. There were men and women, students and elderly people, people wearing trucker hats and people wearing suits. Whole families turned out for the occasion. My companion in line was a well-educated lawyer who shared his knowledge of everything from British history to 1960s pop and, to my shock, had an intimate knowledge of the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli — an obscure theater of World War One for most Americans, but a deeply significant historical touchstone in my home country of New Zealand. A woman behind us loudly proclaimed she was a Democrat, but would be damned if she would vote for Hillary Clinton.

Getting into the minds of Trump supporters has virtually become a cottage industry over the last few months, with writers venturing down to rallies and polling booths to figure out what makes them tick, like explorers entering some far off corner of the Amazon to study an undiscovered tribe. And in fairness, there is much about the Trump phenomenon that demands explanation: What is at the heart of people’s support for Trump? How do they reconcile his defiance of certain Republican orthodoxies? Are they concerned about the tenor of his campaign?

Many of the answers I received were ones that anyone following Trump’s campaign so far will be familiar with. Every single person I spoke to cited Trump’s status as a truth-teller, as someone willing to tell it like it is, as a key factor in their support. They also all pointed to what they viewed as his sterling business record (which, it should be noted, is not all that sterling) as evidence that he would be a good president.

“He knows how to manage money,” one supporter, who identifies as a “conservative libertarian,” told me. “That’s what it all comes down to.”

But I also heard another common argument in favor of Trump, one that suggests the frustrations of his supporters and those of the protesters trying to shut him down may be more similar than either would like to admit. A number of the people I spoke to viewed the U.S. political system as hopelessly corrupt, and believed it was failing ordinary Americans. The only difference was, Trump’s supporters viewed their candidate — who, as he likes to point out, is self-funding his campaign — as the man to fix it.

“He’s not beholden to anybody,” this same supporter told me. “He doesn’t owe anybody any favors. He can’t be bought.”

Joan and Nick are two Republican-leaning voters who expressed a similar sentiment, and both confirmed they’re concerned about money in politics.

“He’s funding his own campaign,” said Joan. “They’re all in it to just promote their own careers and they just want to stay there. You can eat off Washington DC’s streets, they’re so clean. …All our money is funneling in there, it’s got to come back out to the people.”

It was the same message as the one told to me by another Trump-leaning voter back in October of last year: “He’s not supported by outside vendors. He’s not worried about offending anyone, ‘cause he’s got his own money.”

Richard Dix, 54, who says he “flip-flops” between the parties depending on the contest, also viewed a vote for Trump as a vote against the concentration of political power in the hands of a small, privileged elite.

“I just don’t want to see another candidate that gets in there and is another part of the — you know, the U.S. has almost become where royalty are elected to office,” he said. “I just don’t want to see the same people from the same families run our country.”

“I’m suspicious of all the plutocrats that are freaking out over [Trump],” Joan told me.

It was the kind of rhetoric I expected to hear at a Bernie Sanders rally, not here. In fact, one Trump supporter, Joseph, an Austrian immigrant who identifies as a Republican, saw Sanders as the only other candidate he would vote for.

“For me it’s either Trump or Bernie,” he said. “There is no other.”

Although Sanders has chafed at comparisons between his campaign and that of Trump’s — and there is no doubt they are vastly different — the two outsider candidates have a well-documented history of sharing supporters, as well as drawing cross-over votes. In different ways, both have managed to tap into the resentment felt by voters who feel they’ve been left behind by typical politicians, and are anxious about a future of economic uncertainty.

One Trump supporter, Bill Xiong, a Republican, believes Trump’s business experience would be vital to getting the American economy back on its feet. While he disagreed with Trump’s comments in support of Planned Parenthood and accusing George W. Bush of lying about the Iraq War, he was willing to look past them on the basis of the economy.

Likewise, Joan believed Trump’s business knowledge would “get us working.”

“As well as all the bad trade deals,” she added. “The bad trade deals are another reason why I’m pro-Trump.”

Trump’s appeals to nativism get most of the press, but it’s easy to forget the economic populist message that makes up a large chunk of his platform. One need only think of the Huffington Post’s 3-minute supercut of Trump saying “China” that went viral last year. A hilarious masterpiece of editing (Full disclosure: I’ve watched it at least 10 times), it also vividly illustrates the way Trump has made bringing jobs and money back to America from off shore a centerpiece of his campaign — a message that, unlike other parts of his platform, which he seems to have cynically adopted in the last few years, he’s been consistent on.

All of this suggests that Hillary Clinton, who at this point is still the presumptive Democratic nominee, will have significant hurdles to overcome in the general election, provided Trump isn’t denied the GOP nomination in a coup. As someone who represents the hated political establishment, relies on obscene amounts of corporate money and has championed many of the “bad trade deals” that have stung American workers, she will have to work overtime to deflect attacks from Trump on these issues and keep voters from jumping ship.

The ugly side of Trumpism

Of course, this benign image was not the whole story. The Chicago rally also exposed more clearly than ever the ugly face of racism lurking barely beneath the surface of the Trump campaign, which was evident both before and, particularly, after the cancellation of the rally, as clashes between protesters and Trump supporters spilled out onto the street.

One protester, Tymechia Bernard, an African American student, said that there was a sense of hostility from Trump supporters from the moment they got inside.

“The supporters of Trump, they were really hostile,” she said. “There was one man, and he was like, ‘Are you for or against Trump, ‘cause you are black.’”

Bruce Rodriguez, another student, reported something similar.

“There were a bunch of Trump supporters looking at us really ugly,” he said. “I got harassed like three times. This one guy came up and said, ‘Hey, are you a Palestinian terrorist?’”

A Donald Trump supporter waits to enter the UIC rally. (Meg Handler)

Such incidents were not limited to inside the venue. Amira, a Muslim American who had come to protest Trump but hadn’t managed to make it inside, says she and her friends (who were all wearing headscarves) were repeatedly sworn at and told to “go home.”

“One of them said, ‘There’s no freedom of speech here, it’s a Muslim country,’ or something like that, something stupid and ignorant,” she said.

Amira was born and raised in Chicago.

Just before I spoke to her, Amira and her friends were caught up in a scuffle, which she says started when a woman came up and slapped one of her friends in the head. Later, they were part of a sizeable crowd that confronted a young man in a “Make America Great Again” hat, who was defending Trump’s anti-ISIS policies, as well as his call to ban Muslims wholesale from entering the United States.

“The reason [ISIS] is killing Muslims is because they’re saying they don’t follow the Quran as well as they do!” he protested.

“The KKK said they follow the Bible more than anyone else!” one man shouted from the back.

At some point, another young man wearing a “Make America Great Again” cap sidled up to the crowd with a grin on his face and said to the headscarf-clad women: “You guys are violating the Quran. You’re not meant to be this close to a male non-family member.”

Eventually, this scene also resulted in a fight, between a small group of young Middle Eastern men and a few young white men, all of whom looked around student-age.

There was a palpable difference between scenes like this and the supporters I spoke to before things took a turn, who seemed to harbor no explicit racial bias. In fact, many of them dismissed concerns about Trump’s bigotry or allegations of dictator-like behavior, viewing the persona he has created as something akin to a clever marketing ploy and not a true reflection of the man himself.

“He needs to stand out from everybody else, he needs to use a different approach to kind of get the attention,” Joseph told me. “I believe deep inside, he’s not all that crazy … He’s just trying to get people’s attention.”

For Joan, the broad range of criticism Trump had come under was further proof that he was simply ruffling the feathers of the elite.

“The Pope says he’s not Christian,” she says. “That’s all I need to hear. He’s Mussolini, he’s not a Christian. People are just yammering. …That makes me kind of trust him more than I trust them.”

I got the impression that for voters such as these, Trump’s overheated rhetoric, whether about Mexican immigrants or Muslims, was attractive not simply because it was aimed at marginalized and demonized groups; it was also proof positive of his maverick status. The fact that he was willing to so brazenly transgress the norms of polite society fed further into the image he has created for himself as a candidate who won’t be told what to do by outside interests, whether moneyed or otherwise.

Trump’s barely dog-whistling rhetoric therefore works on two levels. For out-and-out racists, it signals he’s one of them, someone who recognizes that white America is increasingly under threat. For the more reasonable voter, it’s a further sign that a President Trump won’t be beholden to anyone upon coming into office.

(Meg Handler)

A spray-tanned totem

Through his campaign, Trump has done something remarkable. Much like Obama in 2008, he has become something of a totem that allows people to project any and all hopes, concerns and solutions onto him.

His supporters cited a wide variety of concerns when explaining their support to me, from immigration to law and order to eliminating Common Core. Yet excluding immigration and trade, it’s difficult to see how Trump’s policy positions on these issues differ in concrete terms from the rest of the GOP field.

Instead, through his invocation of his business acumen, his outsider status and his willingness to offend and say outrageous things, Trump has established himself through personality as the kind of individual who will be able to get things done in a gridlocked Washington, whatever those things happen to be.

One episode towards the end of the night illustrated all of this. A Muslim American man and a Mexican American Trump supporter were having a heated argument. The Muslim American man repeatedly expressed his outrage about Trump’s plan to “deport all minorities.” The only problem was, for all his bluster, Trump has never said such a thing.

Whether you’re for or against Trump, whether you’re a former Grand Wizard of the KKK or an immigrant yourself, you’ll look at the spray-tanned, bizarrely coiffed face of Trump, and see your own fears, hopes and anxieties reflected back.

Branko Marcetic is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine and a 2019-2020 Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting fellow. He is the author of Yesterday’s Man: The Case Against Joe Biden.