Recycling the Steel and Aluminum Already Here Could Take the Sting Out of Geo-Trumponomics

Daniel Cooper

Many economists expect President Donald Trump’s tariffs on imported steel and aluminum to increase what American companies and consumers pay for those metals and the goods made from them. Dozens of companies have already said they will have to fire workers or even go out of business. And, as the retaliatory tariffs Canada, Japan, Mexico and other countries have announced underscore, the United States is heading for a trade war with the nation’s closest allies.

But having spent the last eight years researching how to make the steel and aluminum industries more efficient, I believe it’s possible for the United States to slash imports of these metals not by imposing duties but by boosting the reuse and recycling of old metal products.

Making far more of the nation’s discarded steel and aluminum scrap as good as new would have many advantages aside from its diplomatic dividends, such as cutting pollution and energy consumption.

The United States makes most of its steel and aluminum by recycling scrap metal from manufacturers and from discarded products such as demolished buildings, old cars and thrown away cans.

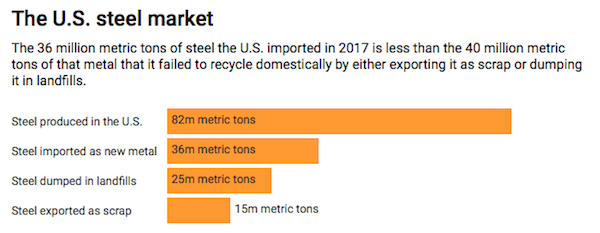

The United States made 82 million metric tons of steel in 2017, enough to form a continuous steel beam that could circle the globe eight times. Some 68 percent of that steel was made from scrap metal.

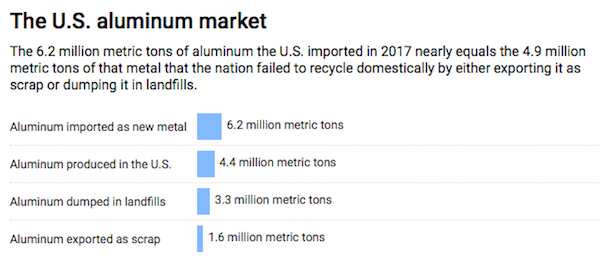

The 4.4 million metric tons of aluminum the United States made in 2017 could be turned into a stack of soda cans tall enough to reach Mars. Some 83 percent of that aluminum was from recycled metal.

While this may sound like an impressive amount of recycling, I believe much more of America’s scrap metal could be recycled domestically. Researchers estimate that only around 65 percent of old U.S. steel products and between 40 and 65 percent of discarded American aluminum products are collected for recycling. The rest of that metal ends up in landfills.

The United States also exports much of the scrap metal that it does collect to countries like Turkey, where it gets recycled.

China has until now been a leading importer of American scrap metal. But it recently began to try to ward off scrap metal imports to retaliate against Trump’s tariffs with stiff duties of its own.

Trade deficits and surpluses

The United States exported 15 million metric tons of steel scrap and imported around 4 million metric tons of it in 2017, running an 11 million metric ton trade surplus.

In the same year, the United States exported 1.6 million metric tons of aluminum scrap, and imported 700,000 metric tons, running a 900,000 metric ton trade surplus.

Even though the United States exports and throws away tons of cheap scrap metal, America imports expensive new metals. It exported 11 million metric tons of new steel and imported 36 million metric tons of it in 2017 — running a 25 million metric ton trade deficit.

In the same year, the United States exported 1.3 million metric tons of new aluminum, and imported 6.2 metric tons—a nearly 5 million metric ton trade deficit.

The Trump administration has deemed this valuable imported metal to be excessive and a threat to American jobs and national security. Those concerns are what led to its decision to slap tariffs on imported steel and aluminum.

Regardless of whether those assertions are reasonable, I believe that these imports, nearly two-thirds of the aluminum and about one-third of the steel the United States consumed in 2017, could be nearly entirely displaced if America were to step up its reuse of scrap metal.

More sustainable

As an already industrialized country, the United States needs little new metal to meet domestic demand.

This is because so many Americans already have all the cars, stoves, washing machines, offices and infrastructure a society could need at a time when the U.S. population isn’t growing much. The average per capita ownership of metal in the United States has remained flat for nearly half a century at around 13 tons.

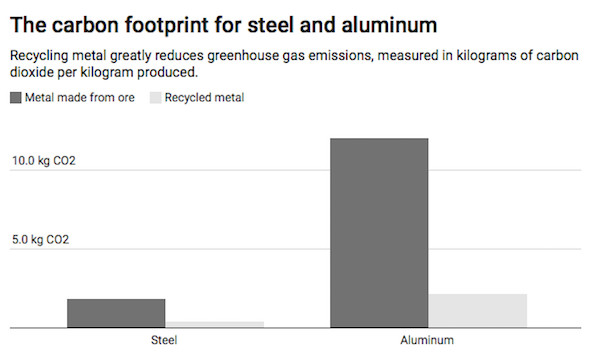

Providing replacements for old cars and demolished buildings by reusing and recycling steel and aluminum is much more environmentally friendly than making metal from ore. Mining iron ore and bauxite, the naturally occurring mineral containing aluminum, destroys habitats and endangers plant and animal life.

Converting these minerals into steel and aluminum releases toxic byproducts as well as 10 percent of all man-made greenhouse gas emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

Making steel from ore requires making iron first using coke, a high-carbon fuel made by baking coal at over 1,000 degrees Celsius. Coke removes oxygen from the iron oxide in the ore, producing iron but inevitably creating carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas then released to the atmosphere.

Between the bauxite mining, refining, smelting and casting processes, the aluminum industry is among the world’s most energy-intensive. Despite some promising technological breakthroughs, the simplest way to make this flexible, durable and strong metal with less power and fewer emissions is by recycling the metal.

Recycling also has a much-smaller carbon footprint. The greenhouse gas emissions for recycling steel are around one-quarter of what they are for making new steel, and recycling aluminum cuts emissions by more than 80 percent.

Recycling challenges

Recycling steel and aluminum entails melting the metals in large electric arc or gas-fired furnaces and casting new metal.

Having a mix of metals in the furnace can lower the recycled metal’s quality. Steel that contains just 0.1 percent copper contamination can be liable to crack during manufacturing.

So recyclers will try to separate discarded old products into piles of different metals before adding any to their furnaces. For example, they shred old cars into small pieces with large mechanical shears before ferreting out the steel they want to recycle with magnets.

This is hard to do well, especially when it comes to, say, removing the copper wiring found in car electronics from shredded steel scrap or taking the steel rivets out of aluminum car panels. Because there is little demand for contaminated metal, U.S. scrap dealers often sell it to buyers in developing countries where low-paid workers sort through the discarded metal by hand.

I believe that increased federal support for metal recycling, such as funding research that would facilitate better scrap metal refining and low-interest loans or tax breaks for recyclers investing in the latest sorting and refining technology, would cost Americans far less than the potential consequences of the new tariffs. It would also slash new steel and aluminum imports while reducing pollution.

(“How recycling more steel and aluminum could slash imports without a trade war” was first published on The Conversation and is reposted on Rural America In These Times under a Creative Commons license. Daniel Cooper does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.)