Veganic: Do Organic Farming and Urban Food Justice Have Room for Animal Rights?

Dayton Martindale

“People always say they’re going to go get local, grass-fed beef, but no one says they’re going to their SPCA to get their local dog meat,” says Nassim Nobari. She is program director and co-founder of the Millahcayotl Association, a group that, according to its website, “seeks to foster sustainable and just food systems that are independent of animal exploitation.”

Nobari was speaking December 6 at the People’s Harvest Forum in San Francisco, a weekend conference organized by Millahcayotl to address food justice, housing issues and urban agriculture through the lens of animal liberation. She says she hopes to adapt the food sovereignty movement — which calls for food production to be healthy, environmentally conscious and, crucially, democratically controlled — so that it no longer looks towards animals as food sources.

The conference also aimed to give animal advocates insights into other agricultural issues. Getting a bunch of vegans to come hear about the Zapatistas’ struggle for autonomy in Mexico, or a San Francisco group working to increase fruit and vegetable access in the (incongruously named) Tenderloin neighborhood — as the People’s Harvest Forum did — creates a rare opportunity for dialogue, says Millahcayotl co-founder Chema Hernández Gil. In fact, Gil and Nobari say they believe their conference is the first to bring together these issues.

The forum began with journalist Christopher Cook, author of Diet for a Dead Planet: Big Business and the Coming Food Crisis (the subtitle has changed since publication, it was originally “How the Food Industry is Killing Us”). Cook, whose work has also appeared in In These Times, painted a grim picture of U.S. agriculture: poor labor conditions, unhealthy food, environmental pollution and increased corporate control — and still people are left hungry.

Society should not blame abuses solely on bad actors, he argues, but also direct its attention to the context within which these actors operate. Corporations like Monsanto, Walmart and Cargill “are not an aberration, they are a natural product of capitalism,” he says.

While Cook’s prognoses are far from rosy, he maintains, “Solutions are already out there.” Organic and agro-ecological food production is proven to work, he says, so the problem is not one of technology but instead of “economics and politics and power.”

He didn’t explicitly advocate a vegan diet but called on people to eat less meat, citing the industry’s disregard for human workers, ecological impacts and farmed animal welfare.

While the conference was specifically themed around animal liberation, many of the first day’s speakers did not feature animal ethics in their organization’s work or in their presentations.

Improved animal welfare standards are a common goal for food reformers, but for many they are not a top priority. Even those who put animal treatment in the foreground — for example, Joel Salatin, whose work has been featured in Rural America In These Times—often call for a “humane” approach to meat, dairy and eggs as opposed to a fully vegan food system. Salatin and others support animals having ample space to pursue biologically ingrained behaviors and live a happy, healthy life, with slaughter as quick and painless as possible. This conference, said organizers, was aimed to start putting animal liberation — an end to the slaughter altogether — into the conversation.

Another first day speaker was Hernández Gil, with a talk entitled “The Collapse of Traditional Mexican Food Systems.” He had grown up in a small town (coincidentally, also named San Francisco) made up largely of indigenous people in Mexico, with local, plant-based agriculture. (In fact, the name “Millahcayotl” comes in part from “milpa,” the Nahuatl word for the traditional cultivation of squash, corn and beans.)

According to Gil, his rural village’s time-honored food customs have been changing in large part due to cheap U.S. corn (especially since NAFTA, he said) and the influx of corporations like Coca-Cola.

The forum’s second morning was accompanied by a whole lot of organic persimmons, grown about 150 miles away by farmer Helen Atthowe. (Ever the intrepid reporter, I gave one a try. And then another.)

The first day had dealt in various ways with corporate influence on the food supply, and while the second day didn’t drop this theme, it also more directly confronted the animal question.

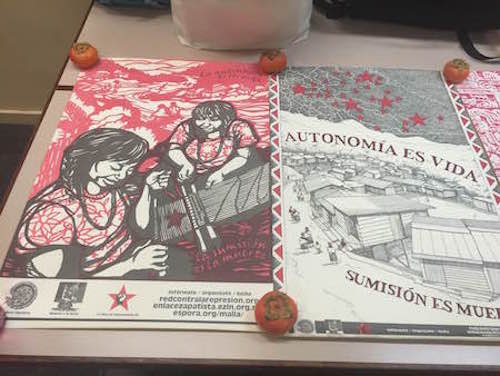

At the conference, Zapatista posters were held down at the corners by veganic persimmons. (Photo: Dayton Martindale)

A “veganic” approach to farming

Atthowe has been a certified organic farmer since 1988, and has since transitioned to “veganic.” This refers to organic production without using material from captive animals, even manure (although some wild animals, including pollinators and earthworms, play a role).

She says that growing up on a cattle farm, where “we gave those cows life and then we killed them,” soured her against killing. She has since tried to make an “unconditional effort to keep all things alive and growing.”

While she said she holds a high opinion of organic farming, she added she feels conventional organics fail to make this effort. She claimed her methods — no insecticides, no clearing land to control weeds, manure-free fertilizer — not only work but ultimately help her farm be more productive. An audience member questioned whether her approach could be scaled up to feed all humanity. Atthowe says she was “not going to say it’s going to be easy,” but insisted she believed it was possible.

Joe Kilcoyne, co-founder of Wild Earth Farm and Sanctuary in Kentucky, was another vegan permaculture farmer speaking at the conference. Wild Earth is a refuge for pigs and ducks (with plans to open up to other species) as well as an organic permaculture food producer. Unlike Atthowe’s, Kilcoyne’s vegetable farm uses manure fertilizer from nonhuman—and human — sources.

Kilcoyne criticized human coercion over humans and nonhumans alike, and called for an anarchist society based on mutual, voluntary interactions. An activist for years, he said removing himself from relationships built on force, and trying to create a peaceful alternative to the state could be more effective than direct confrontation.

Another speaker, Eugene Cooke, of the organization Grow Where You Are urged attendees — many of whom had an activist background — to “avoid the conflict and be creative.”

Originally from south central Los Angeles and now based in Atlanta, Cooke helps create community gardens in cities, and has worked his own veganic urban farm since before he knew the word “veganic.”

“Often I’m invited to spaces like these being the only black man talking to you about growing food,” he says, noting last weekend’s event was no exception. “Considering this country’s history, that’s ironic,” he adds.

“The reason I grow food is because other than that I have no connection to this place,” meaning America, he later adds. “So I touch the earth every single day just to know that I’m still relevant.”

A father, veganic farmer and co-founder of Grow Where you Are, Eugene Cooke has traveled around the world helping to set up small-scale, intensive local food systems. (Photo: prlog.org)

Food, community and the price of rent

Wrapping up the conference were housing activists Chirag Gunvantbhai Bhakta and Oscar Grande, who discussed the risk that community gardens and health food stores can drive up rent prices. In low-income communities, health and environmental initiatives can be seen as harbingers of gentrification.

For individuals struggling to maintain shelter, they suggested, vegetables and animal rights aren’t always the highest priorities.

The question of whether the housing crisis must be solved before the food crisis, or whether both problems can be attacked at once, brought comment from Atlanta grower Cooke.

One of his community farms in Atlanta had helped make the area a tourist spot, displacing the homeless, he explains. “Damn,” he had thought. “I was the first tool of gentrification.”

But pitting food and housing justice against each other is counterproductive, Cooke says. He adds that despite the outcome of gentrification, he had also created a space for people to come together and learn about each other and their food, and came away with ideas for what to do differently next time.

One audience member from an animal advocacy network asked what his organization could do to support housing and economic justice groups. The answers were complicated, and they continued talking after the forum officially ended, but Bhakta and Grande did agree on one thing: Their groups would welcome donations of free vegan food for meetings.

Grande’s organization, People Organizing to Demand Environmental and Economic Rights (PODER), helps run an urban garden. He says it “doesn’t yield a lot of food,” but that his group measures the garden’s success in terms of building community and spreading knowledge.

As another speaker, Antonio Roman-Alcala, had noted the previous day, urban gardens cannot provide all the food cities need. There is simply not enough space, he pointed out, and urban agriculture lacks the government subsidy structure that sustains conventional farming.

So even in San Francisco, food sovereignty does not mean breaking ties with the rural. But some argue it should mean breaking ties with the slaughterhouse.

Dayton Martindale is a freelance writer and former associate editor at In These Times. His work has also appeared in Boston Review, Earth Island Journal, Harbinger and The Next System Project. Follow him on Twitter: @DaytonRMartind.