New Research Shows Immigrants Working in Rural America are More Likely to Live in Poverty

Alex McLeese

While much attention has been given to rural America’s changing demographics, little is known about how conditions for rural immigrants compare to those for their native-born neighbors or for immigrants living in cities. But a new study from the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy hopes to shine some light on the subject. It reveals that working rural immigrants are almost twice as likely to be poor as their nonimmigrant counterparts.

According to Daniel Lichter, a sociology professor at Cornell, “Rural areas tend to get ignored by policy-makers concerned about immigration, we tend not to think of rural areas as a destination for immigrants.”

University of New Hampshire researcher Andrew Schaefer, who co-authored Demographic and Economic Characteristics of Immigrant and Native-Born Populations in Rural and Urban Places with his colleague Marybeth Mattingly, saw an opportunity in the absence of available information. “We looked at a number of different studies to try to see if we were replicating work already done or if there were gaps in the literature, and we found that there wasn’t as much stuff on immigrants in rural places. Work often had just a Hispanic focus or a Mexican immigrant focus, and there was a lot on urban immigrants, so we found a hole we could fill,” he says. “There was no comprehensive project comparing rural immigrants to other people in rural places or to urban immigrants, and it’s useful to have something like that all together in one piece with the most recent data.”

What the study reveals

The data employed by the study came from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey five-year estimates from 2010 to 2014.

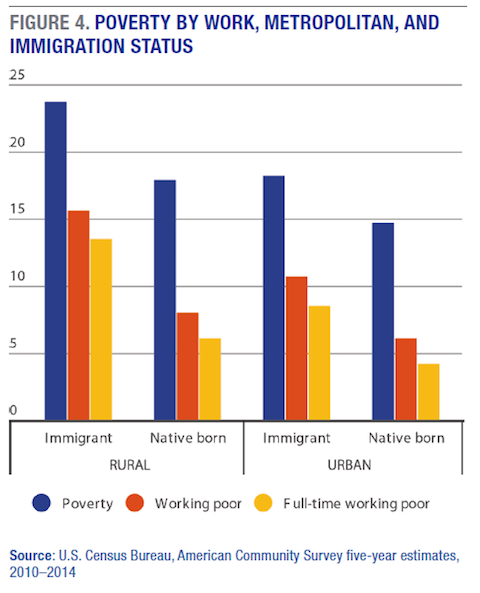

The study shows that rural immigrants are more likely than native-born rural residents to live in poverty, at 23.7 percent compared to 17.9 percent. Immigrants who obtain citizenship fare better than non-citizens. The poverty rate for rural non-citizen immigrants is 31.6 percent, compared to 13.7 percent for citizens. In 2014, for a family of four including two children, the poverty threshold was $24,008.

“Especially among rural immigrants working full time, the poverty rate for that group is surprisingly high,” says Schaefer.

According to the study, poverty among working rural immigrants stands at 15.6 percent. By comparison, the rate for the working rural native born is just 8 percent, and the figure for working urban immigrants is 10.7 percent.

(Image: carsey.unh.edu)

In all age groups, the poverty rate for rural immigrants exceeds the rate for their urban counterparts.

Experts offer several reasons for this difference. “Urban immigrants are more skilled, with different jobs, and are more likely to be in an ethnic community that might provide resources in times of need,” says Lichter. “There’s also information about job possibilities, and better education with English language as second language.”

University of New Hampshire sociology professor Kenneth Johnson says that in urban areas “better jobs are prevalent, with higher incomes, so the younger immigrant population is likely to move to those areas. Immigrants can feel less isolated in urban areas, with more compatriots. They don’t stick out the way they do in rural areas, and they have more social networks in urban areas, which gives them more economic access.”

Schaefer says that rural policy-makers face challenges that are different from their urban counterparts, and that his research could be relevant for public policy decisions. “My guess is that a lot of the policies aimed at the immigrant population in particular are urban-centric, and might work better in urban places,” he says. For example, he says, distributing social services in sparsely populated rural areas is particularly challenging.

According to Lichter, one effective way to address rural poverty among rural immigrants would be to change our national immigration polices. “We need comprehensive immigration reform to provide some sort of pathway to permanent residence, not necessarily citizenship but to make immigrants legal and not in the shadows. Then they could find a way to invest in their own skills and provide good care for their children, often U.S. citizens, who are born here,” he says, adding, “It would be a good thing to think more about a guest worker program that was carefully monitored.”

A closer look

The study also gathered information about rural immigration beyond poverty rates that shows major differences between rural and urban populations.

First, immigrants make up a relatively small part of the rural population — accounting for 4.8 percent of the rural population, compared to 16.6 percent of urban residents.

Rural immigrants are more likely than their urban counterparts to be Hispanic and non-Hispanic white. A majority, or 54.2 percent, of all rural immigrants are Hispanic, and 25.9 percent are non-Hispanic white. In urban areas, 44.1 percent of immigrants are Hispanic, and 20.2 percent are non-Hispanic white.

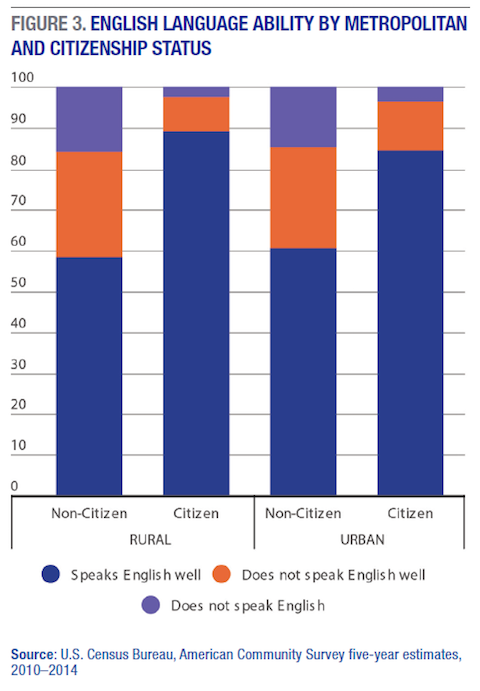

Rural immigrants also tend to be less educated. 39.4 percent have obtained less than a high school diploma or equivalent, compared to 29.2 percent among urban immigrants. However, English language ability is similar for urban and rural immigrants. 71.6 percent of rural immigrants speak English well, compared to 72.3 percent of urban immigrants.

(Image: carsey.unh.edu)

The study also includes data about families. Rural immigrant family structures are relatively stable. 60.1 percent of rural immigrant adults are married, compared to 53.5 percent of rural native born. 35.2 percent of rural immigrant adults have children under 18, compared to 23 percent of native-born rural adults.

While adding to the existing body of work on immigrant and rural poverty, the study’s authors ask an important question: “What are the short- and long-term consequences of an economic climate in which full-time work doesn’t necessarily lead to economic stability and in which the safety net doesn’t meet the needs of poor residents?”

Schaefer answered his own question: “It’s hard to imagine how outcomes could be positive when we have vulnerable groups in the United States and the safety net is not performing well in meeting the needs of these groups.”