The Food Movement Has People and Can Make the World a Better Place…But It Will Need Land

Rural America In These Times

In November, Agrarian Trust held its second “Our Land” symposium in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, N.M. The Trust, a collaboration between the Schumacher Center for New Economics and Greenhorns, a grassroots network for young agrarians, is working to secure land access for the next generation of farmers. This is important. In the next 20 years, as today’s farmers age and retire, American Farmland Trust estimates 400 million acres of U.S. farmland will change hands. “Hands” plural might be optimistic. Without intervention, the increasing value of farm real estate nationwide will continue to price-out new entrants to farming. Furthermore, as those acres hit the open market they are likely to go where the money is. These days, that usually means becoming disembodied terrestrial testing grounds for our always-expanding, always-consolidating multinational agribusiness corporations as they pursue new and cutting-edge petro-chemical applications (for us to eat).

Over several days, Our Land 2: Tracing the Acequia Commons featured speakers from many facets of the sustainable food movement — farmers, conservationists, water experts, people from frontline communities, artists, activists, professors and lawyers — who focused on what it will take to build a less diabolical food system in the United States.

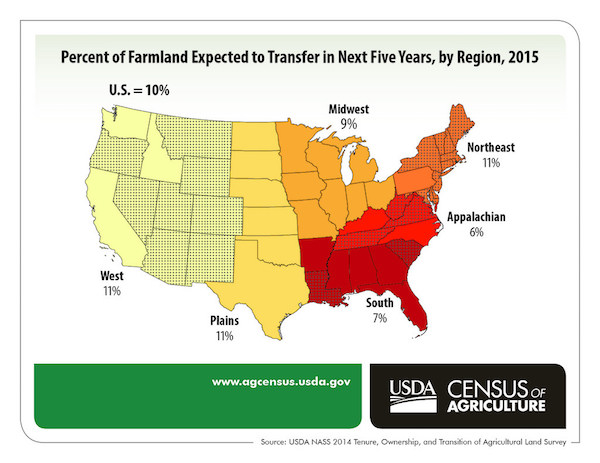

(For regional maps and additional farmland data, click here.)

Videos of these presentations have been uploaded to the Trust’s website and a lecture titled “Land relations: Conflict, subsistence, extraction, compromise and utopia of our domesticated nature,” by Eric Holt-Giménez, is worth a watch.

Holt-Giménez is the executive director of The Institute for Food and Development Policy, also known as Food First. According to his bio on foodfirst.org:

Eric Holt-Giménez has been executive director of Food First since 2006. He is the editor of the Food First book Food Movements Unite! Strategies to Transform Our Food Systems; co-author of Food Rebellions! Crisis and the Hunger for Justice with Raj Patel and Annie Shattuck; and author of the book Campesino a Campesino: Voices from Latin America’s Farmer to Farmer Movement for Sustainable Agriculture, and of many academic, magazine and news articles. Of Basque and Puerto Rican heritage, Eric grew up milking cows and pitching hay in Point Reyes, Calif., where he learned that putting food on the table is hard work. After studying rural education and biology at the University of Oregon and Evergreen State College, he traveled through Mexico and Central America, where he was drawn to the simple life of small-scale farmers.

In the 51-minute presentation, embedded below, Holt-Giménez offers his take on what he calls the “capitalist food regime.” He says that though our current approach to agriculture is thousands of years in the making, “the forms of ownership at the core of today’s food and farming system have changed surprisingly little since early colonization.” These forces, he says, have turned the United States into the “center of a powerful, multi-trillion dollar, global food machine” — a machine that, despite what we are told, fosters poverty, hunger and ecological destruction. Holt-Giménez is pessimistic about global capitalism ever embracing sustainable solutions because he, like many, has deduced that the need for constant economic growth will require nothing short of ecological suicide. He acknowledges that establishing an alternative system is a long-shot that probably won’t work, but says this counter-movement — towards agroecology, sustainable farming and food sovereignty — has enough people on-board and is, in many aspects, already thriving around the world. What the movement doesn’t have, he says, is land:

“Even as the pressures of industrialization and financialization push many farmers out of agriculture, a contingent of farmers are increasingly avoiding the destructive inputs pushed on them by the seed and chemical industries. Moreover, a growing number of consumers reject the poisonous processed food sold by the agrifoods industry. Rural and indigenous communities are rising up to resist fracking, pipelines, CAFOs. Farmers and farmworkers are organizing strikes and boycotts against starvation wages and inhumane working conditions. Across the entire country there are instances of older and beginning farmers forging agroecology, permaculture, organic and urban agriculture — who are working with consumers to get fresh and healthy food to the people who need it most. There are counter-movements for food justice and food sovereignty growing in rural and urban communities all over the United States. People from all walks of life are looking to return to farming. It’s an exciting time.

The food movement is stretching its imagination across rural and urban areas from farm to fork. Paradigms, practices and politics are all changing — changes that are being vigorously resisted by the agencies and corporations of the existing food machine. Unlike the past, in which land, work and territory defined peoples’ resistance, today the entire food system makes up a turbulent struggle — from the fight for a better minimum wage to the struggles against pipelines. But the farmers on the frontlines of this new agrarian struggle are finding that the efforts to build healthy equitable food systems — ones that provide jobs, that keep the food dollar in the community — are inevitably limited by the lack of access to one essential resource: Land.”

Holt-Giménez doesn’t hold back when describing what he finds wrong with mankind’s current trajectory, but he also articulates why he believes the eclectic and diverse food movement is uniquely positioned to transcend politics and actually change things for the better. He also warns against the possible rise of fascism and the loss of hope. A brief and interesting Q&A concludes the lecture. Check it out and let us know what you think in the comments section.