The Trump administration would like to slash what the government spends on food for low-income Americans.

Its latest budget proposal calls for reducing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) outlays by $200 billion over the next decade and replacing about half of the aid delivered through this mainstay of the American safety net with what it’s calling “harvest boxes” of nonperishable items like pasta, canned meat and peanut butter. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue says this new approach would cut costs and give states, which administer the SNAP program, “flexibility.”

While researching the history of SNAP and other government efforts to help Americans who face economic hardship get enough to eat, I have been struck by how, while the leaders who pioneered the program and its precursors were Democrats, it has long benefited from bipartisan support. Even as other welfare spending was cut, the kind of assistance that used to be called food stamps has persisted.

SNAP’s backstory

As part of his New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt broke with a governmental tradition of leaving the job of fighting hunger entirely to charities.

Initially, his administration sought to alleviate the spiking poverty rate brought about by the Great Depression by directly distributing surplus pork, dairy products, flour and other surplus food to people who had trouble getting food on the table.

FDR’s administration then adopted a new model in 1939 that used food stamps for the first time in a short-lived program. Low-income people could buy stamps and redeem them for groceries worth 50 percent more than what they spent — as long as they spent the bonus ones on items designated as “surplus,” such as eggs, butter and beans.

Beneficiaries could, for example, pay $10 for $15 worth of stamps. They would be free to spend the orange-colored stamps they’d get with the $10 from their own pockets on any groceries they wanted. The $5 in free blue-colored stamps that came as a bonus, however, could buy only surplus food.

The program ended four years later amid the economic and employment boom World War II brought about. But some lawmakers continued to support the concept of establishing a permanent version.

President John F. Kennedy, who had expressed shock upon witnessing dire poverty in West Virginia when he ran for office, immediately made food stamps widely available again through an executive order that expanded a small-scale USDA program already in place. Like its FDR-era precursor, the measure required beneficiaries to spend some of their own money before they could get this assistance.

Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy’s successor, signed the Food Stamp Act of 1964, codifying the program, which took another decade to spread nationwide.

Republicans also championed food stamps. President Richard Nixon expanded the program’s reach during his administration. Senator Bob Dole, a Kansas Republican, led the charge with Sen. George McGovern, a South Dakota Democrat. Working together, they got the Food and Agriculture Act of 1977 passed.

Following that law’s enactment, beneficiaries no longer had to buy the food stamps. The measure also made food stamp fraud much harder to pull off and therefore rare by introducing federal funding for states to crack down on abuses and introducing incentives for low error rates.

Food stamps then survived the welfare overhaul of 1996, which sharply restricted eligibility for other kinds of government assistance for the poor. Yet lawmakers left the food stamp program intact, making it the only remaining option available for millions of low-income Americans.

In 2002, President George W. Bush expanded access to this nutritional support program for immigrants with legal status in a concrete example of what he meant when he embraced “compassionate conservatism.”

Six years later, the government rebranded the program as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. By that point, the stamps themselves had been gradually replaced across the country with a more modern mechanism. Americans eligible for these benefits were instead getting their groceries subsidized electronically at checkout counters by using plastic cards known as EBTs—as mandated when the government undertook welfare reform. Among other things, the cards made it harder to commit fraud because no one could sell the stamps instead of using them to buy their own groceries.

For the most part, the federal government has avoided getting involved with the direct distribution of food. Exceptions include its decision to give “government cheese” to the poor during the recession of the early 1980s and a longstanding practice of distributing food — especially nonperishable items—on Indian reservations.

The bid to fight hunger with stockpiled processed cheese during the Reagan administration proved relatively brief and hard to pull off for logistical reasons. But “government cheese” has lived on through punchlines in movies, TV shows and music.

Carrying on

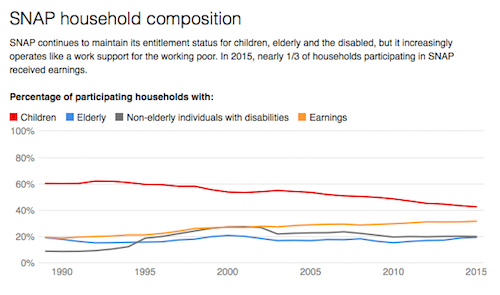

More than 40 million Americans now get food assistance through SNAP, a federal program administered by the states. Large shares of the households getting these benefits include children or members who earn money but not enough to make ends meet. And the program has a proven track record of reducing poverty and hunger.

The total tab, which rises when the economy falters and declines during boom times, was about $68 billion in 2017.

I believe that Trump’s harvest-box concept would be a logistical nightmare to carry out. In the rather unlikely event that the cuts he seeks do happen, it would become harder for low-income people to get healthy food.

That, in turn, would increase the already large burden on food banks and other nonprofits helping the many Americans who slip through the safety net in good times and bad to avoid hunger.

(“From FDR’s food stamps to Trump’s harvest boxes: The history of helping the poor get enough to eat” was first published on The Conversation and is reposted on Rural America In These Times under a Creative Commons license. Disclosure statement: The author does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.)