SAN LEANDRO, CA — Within days of each other last week, two groups of Northern California recycling workers declared they’d had enough of what they see as regimes of indignity and discrimination. One group voted to unionize, and another, already union members, walked out on strike.

“They think we’re insignificant people,” declares striker Dinora Jordan. “They don’t think we count and don’t value our work. But we’re the ones who find dead animals on the conveyor belts. All the time we have to watch for hypodermic needles. If they don’t learn to respect us now, they never will.”

Jordan’s employer is Waste Management, Inc. (WMI), a giant corporation that handles garbage and recycling throughout North America. In just the second quarter of 2014 WMI generated $3.56 billion in revenue and $210 million in profit, “an improvement in both our net cash provided by operations and our free cash flow,” according to CEO David P. Steiner.

Shareholders received a 35 cent per share quarterly dividend, and the company used $600 million of its cash in a massive share buyback program. Two years ago Steiner himself was given 135,509 shares (worth $6.5 million) in a performance bonus, to add to the pile he already owns.

But at its San Leandro, California, facility, WMI had been unwilling to settle a new contract with Jordan’s union, Local 6 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, for three years.

Last week, she and members of the negotiating committee returned to the facility after another fruitless session. They called workers together to offer a report on the progress in bargaining — standard practice in Local 6.

One supervisor agreed to the shop floor meeting, but another would not. The workers met anyway. Then the second supervisor told the vast majority of the workers except a handful needed to continue running the facility to clock out and go home — a disciplinary measure that would at least dock the rest of the day’s pay.

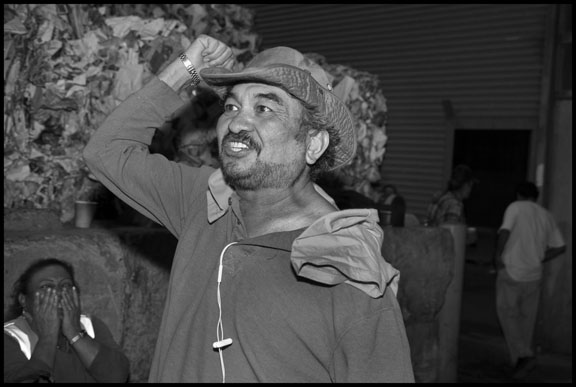

Strikers at the Waste Management recycling facility.

“That’s when we finally said ‘Enough!’” Jordan explains. “As a union, we support each other. If some of us can’t work, then none of us will.”

Workers walked out on an unfair labor practice strike, and immediately met at the union hall and voted to strike. That strike ended yesterday, after a week.

At another facility in the same city, workers at Alameda County Industries were equally angry. At the end of a late night vote count in a cavernous sorting bay, surrounded by bales of recycled paper and plastic, agents of the National Labor Relations Board unfolded the ballots in a union representation election.

When they announced that 83 percent had been cast for Local 6, workers began shouting “¡Viva La Union!” and dancing down the row of lockers.

Sorting trash is dangerous and dirty work. In 2012, two East Bay workers were killed in recycling facilities. With some notable exceptions, putting your hands into fast moving conveyor belts filled with cardboard and cans does not pay well — much less, for instance, than the jobs of the drivers who pick up the containers at the curb. And in the Bay Area, the sorting is done almost entirely by women of color, mostly immigrants from Mexico and Central America and African Americans.

Just after voting, in the ACI barn with pallets full of recycled waste.

This spring, recycling workers at Alameda County Industries — probably those with the worst conditions — began challenging their second-class status. Not only did they become activists in a growing movement throughout the East Bay, but their protests galvanized public action to stop the firings of undocumented workers.

At ACI, garbage trucks with recycled trash pull in every minute, dumping their fragrant loads gathered on routes in Livermore, Alameda and San Leandro. These cities contract with the firm to process their trash. In the Bay Area, only one city, Berkeley, picks up its own garbage. All the rest hold contracts with private companies; even Berkeley contracts recycling to an independent sorter.

ACI contracted with a temp agency, Select Staffing, to employ the workers on the lines. Sorters therefore have no health insurance, vacations or holidays. Wages are very low, even for recycling: After a small raise two years ago, sorters get $8.30 per hour on day shift and $8.50 at night.

A year ago, workers discovered this was an illegal wage. San Leandro passed a Living Wage Ordinance in 2007, mandating (in 2013) $14.17 per hour or $12.67 with health benefits. Last fall, some of the women on the lines received leaflets advertising a health and safety training for recycling workers put on by Local 6.

The union’s organizing director Agustin Ramirez says, “When they told me what they were paid, I knew something was very wrong.”

Ramirez put them in touch with a lawyer, who sent ACI and Select a letter stating workers’ intention to file suit for back wages. In early February, 18 workers, including every person but one who’d signed, were told that Select had been audited by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) a year before. ICE, the company said, was questioning their immigration status.

Workers cheer after the vote total is announced at Alameda County Industries.

Instead of quietly disappearing, though, about half the sorters walked off the lines on February 27, protesting the impending firings. They were joined by faith leaders, members of Alameda County United for Immigrant Rights, and workers from other recycling facilities, including WMI. The next week, however, all eighteen accused of being undocumented were fired.

“Some of us have been there 14 years, so why now?” wondered sorter Ignacia Garcia.

Despite fear ignited by the firings and the so-called “silent” immigration raid, workers began to join the union. Within months, workers were wearing buttons and stickers up and down the sorting lines. At the same time, sorters went to city councils, denouncing the raid and illegal wages, asking councilmembers to put pressure on the company processing their trash.

By the time Local 6 asked for the election, ACI had stopped campaigning against the union, likely out of a fear of alienating its city clients, and had ended its relationship with the temp agency. In last week’s balloting, only one worker voted for no union, while 49 voted for the ILWU.

Because cities give contracts for recycling services, they indirectly control how much money is available for workers’ wages. That’s taken the fight for more money and better conditions into city halls throughout the East Bay.

Waste Management, Inc., has the Oakland city garbage contract, and garbage truck drivers have been Teamster members for decades. When WMI took over Oakland’s recycling contract in 1991, however, it signed an agreement with ILWU Local 6. Workers had voted for Local 6 on the recycling lines, at the big garbage dump in the Altamont Pass and even among the clerical workers in the company office.

At WMI, workers also faced immigration raids. In 1998, sorters at its San Leandro facility staged a wildcat work stoppage over safety issues, occupying the company’s lunchroom. Three weeks later, immigration agents showed up, audited company records and eventually deported eight of them. And last year, three more workers were fired at WMI, accused of not having legal immigration status.

When Teamster drivers were locked out of WMI in 2007 for more than a month over company demands for concessions, Local 6 members respected their lines and didn’t work. That was not reciprocated, however, when recyclers staged their walkouts over firings last year.

Last week the Teamsters told drivers to cross Local 6 lines again. One unidentified Teamster officer told journalist Darwin Bond-Graham that Local 6 had not asked for strike sanction.

“Our members can’t just stop working,” he said.

Local 6 officers say they have asked for sanction. Relations between the two unions grew even tenser when the Teamsters, which also represent drivers at Alameda County Industries, appeared on the ballot in the election for the recycling workers. The Teamsters received nine votes.

A striking ILWU member appeals to Teamster drivers to respect their picket lines.

Under the contract that expired three years ago, WMI sorters got $12.50 — more than ACI, but a long way from San Francisco, where Teamster recyclers get $21 an hour. To get wages up, recycling workers in the East Bay organized a coalition to establish a new standard, the Campaign for Sustainable Recycling.

Two dozen organizations belong to it in addition to the ILWU, including the Sierra Club, the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, Movement Generation, the Justice and Ecology Project, the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy and the Faith Alliance for a Moral Economy.

San Francisco, with a $21 per hour wage, charges garbage rates to customers of $34 per month. East Bay recyclers pay half that wage, but East Bay ratepayers still pay $28-30 for garbage, recycling included. The bulk of that money clearly isn’t going to the workers.

Waste Management strikers stop a truck.

Fremont became the test for the campaign’s strategy of forcing cities to mandate wage increases. Last December, the Fremont City Council passed a 32 cent rate increase with the condition that its recycler, BLT, agree to raises for workers. The union contract there now mandates $14.59 per hour for sorters this year, finally reaching $20.94 in 2019.

Oakland has followed, requiring wage increases for sorters as part of its new recycling contract. That contract was originally going entirely to California Waste Solutions, but after WMI threatened a suit and a ballot initiative, it recovered its half of the city’s recycling business.

The new Local 6 contract which ended the strike yesterday follows the pattern laid out by the new Oakland city requirement on its recyclers. Workers will get a signing bonus of $500 to $1,500, depending on seniority, to compensate for the three years worked under the old contract. They will all get an immediate raise of $1.48 per hour, and 50 cents more on New Year’s. Starting next July, wages will rise $1.39 per year until 2019, when the minimum wage for sorters will be $20.94. The strikers at WMI ratified their new agreement by a vote of 111 to 6.

Yet this strike was about much more than money. Over the last week, workers from Alameda County Industries would come by the picket lines after their shift ended, to help the strikers. While they also undoubtedly would like their wages to rise to this new standard, for both groups, this was a battle to end the second class status of the sorters.