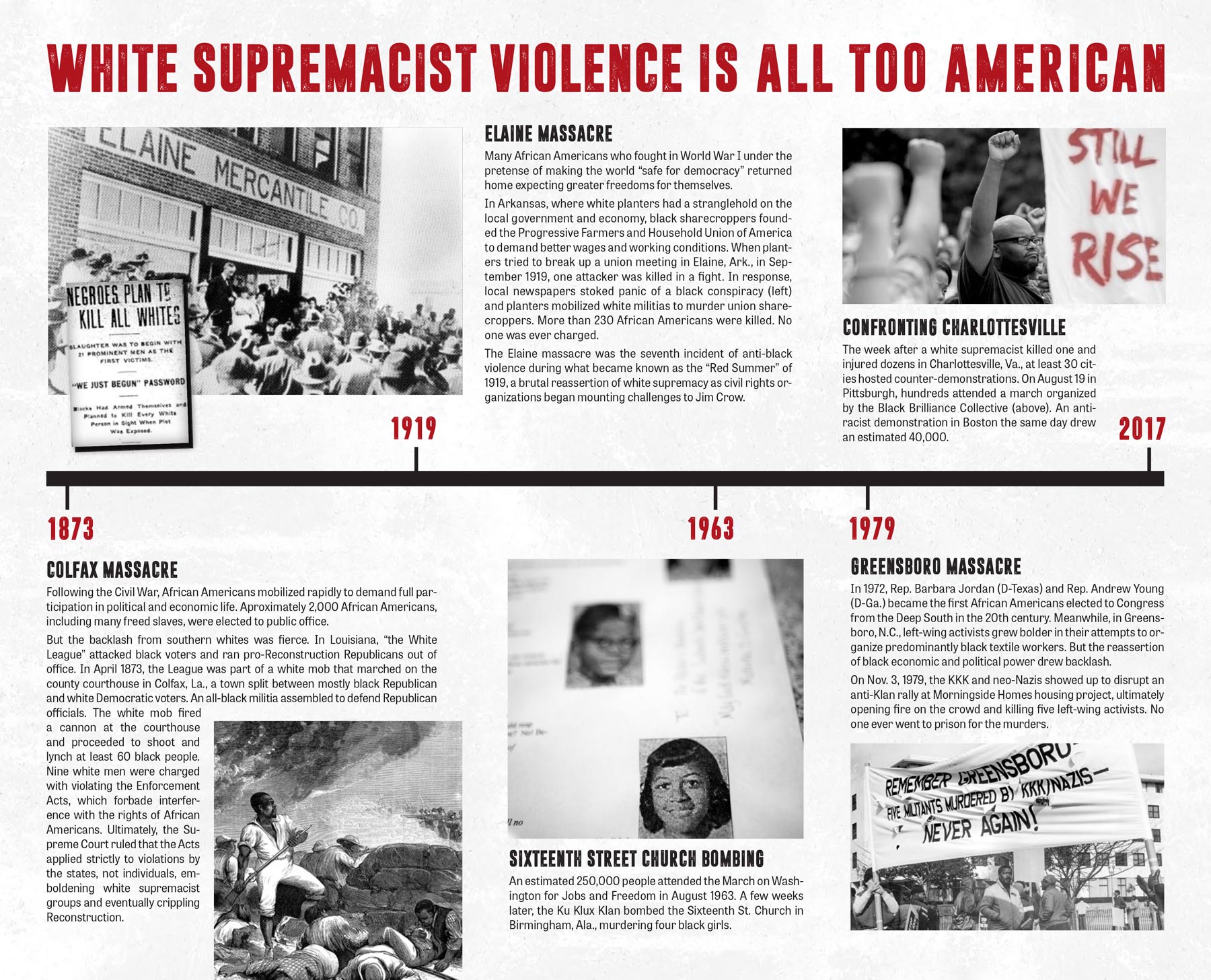

White Supremacist Violence Is All Too American

Whenever Black Americans make advances, they face a torrent of racist backlash.

Robert Greene II

Real Americans understand that our nation is built around values,” wrote New York Times columnist Paul Krugman following the deadly right-wing violence in Charlottesville, Va. “These days we have a president who is really, truly, deeply un-American, someone who doesn’t share the values and ideals that made this country special.”

Make no mistake: The resurgence of armed white supremacist groups is exceedingly dangerous. Donald Trump’s refusal to unequivocally condemn them perhaps even more so. But what does it mean to call these behaviors un-American?

Studying U.S. history means coming to terms with right-wing terrorism as a feature, not a fluke, of the American experience.

This violence often surges at moments when American values and ideals are most hotly contested. Consider an editorial by Ku Klux Klan (KKK) Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans in 1925, when immigration and civil rights were front-page news. “Within a few years, the America of our fathers will either be saved or lost,” Evans wrote in the mainstream magazine The Forum. “All who wish to see it saved must work with us.” This echoes the chants of torch-bearing marchers in Charlottesville: “You will not replace us.”

Conversely, the unfulfilled promise in the American ideal of “liberty and justice for all” has given birth to many movements determined to win its fullest possible expression. For every theoretician of “race science” or proponent of “separate but equal,” we will find abolitionists and civil rights activists. These two forces are the yin and yang of the American spirit. At our core, we are a nation still struggling over wildly different interpretations of American values. Simply stating that the events in Charlottesville and Trump’s response are “un-American” risks the impression that this battle has already been won.

Here, I consider four key periods when rightwing violence helped derail civil rights gains. The lesson is sobering: Any successful liberation movement is likely to encounter right-wing backlash. The battle between America’s anti-racist ideals and its racist id continues. Beyond disavowing the latter, we must continue the fight for the former.

1873: Colfax Massacre

Following the Civil War, African Americans mobilized rapidly to demand full participation in political and economic life. Aproximately 2,000 African Americans, including many freed slaves, were elected to public office.

But the backlash from southern whites was fierce. In Louisiana, “the White League” attacked black voters and ran pro-Reconstruction Republicans out of office. In April 1873, the League was part of a white mob that marched on the county courthouse in Colfax, La., a town split between mostly black Republican and white Democratic voters. An all-black militia assembled to defend Republican officials. The white mob fired a cannon at the courthouse and proceeded to shoot and lynch at least 60 black people. Nine white men were charged with violating the Enforcement Acts, which forbade interference with the rights of African Americans. Ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled that the Acts applied strictly to violations by the states, not individuals, emboldening white supremacist groups and eventually crippling Reconstruction.

1919: Elaine Massacre

Many African Americans who fought in World War I under the pretense of making the world “safe for democracy” returned home expecting greater freedoms for themselves.

In Arkansas, where white planters had a stranglehold on the local government and economy, black sharecroppers founded the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America to demand better wages and working conditions. When planters tried to break up a union meeting in Elaine, Ark., in September 1919, one attacker was killed in a fight. In response, local newspapers stoked panic of a black conspiracy and planters mobilized white militias to murder union sharecroppers. More than 230 African Americans were killed. No one was ever charged.

The Elaine massacre was the seventh incident of anti-black violence during what became known as the “Red Summer” of 1919, a brutal reassertion of white supremacy as civil rights organizations began mounting challenges to Jim Crow.

1963: Sixteenth Street Church Bombing

An estimated 250,000 people attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963. A few weeks later, the Ku Klux Klan bombed the Sixteenth St. Church in Birmingham, Ala., murdering four black girls.

1979: Greensboro Massacre

In 1972, Rep. Barbara Jordan (D-Texas) and Rep. Andrew Young (D-Ga.) became the first African Americans elected to Congress from the Deep South in the 20th century. Meanwhile, in Greensboro, N.C., left-wing activists grew bolder in their attempts to organize predominantly black textile workers. But the reassertion of black economic and political power drew backlash.

On Nov. 3, 1979, the KKK and neo-Nazis showed up to disrupt an anti-Klan rally at Morningside Homes housing project, ultimately opening fire on the crowd and killing five left-wing activists. No one ever went to prison for the murders.

2017: Confronting Charlottesville

The week after a white supremacist killed one and injured dozens in Charlottesville, Va., at least 30 cities hosted counter-demonstrations. On August 19 in Pittsburgh, hundreds attended a march organized by the Black Brilliance Collective. An antiracist demonstration in Boston the same day drew 1919 an estimated 40,000.