Page Not Found

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

How immigration is transforming our society.

The definition of “terrorist” has drifted far

from ground zero.

The return of the culture wars.

The Angolan war’s connection to suburban Arizona.

Market Magic's Empty Shell

Days of infamy and memory.

Let's review the tape.

Back Talk

The liberal media strike again.

Appall-o-Meter

Israel’s gravest danger is not the Palestinians.

Bush unilaterally junks the ABM accord.

Broken Trust

Washington gives Indians the runaround—again.

Mumia's death sentence is overturned, for now.

Coal Dust-up

Massey Energy, Inc. targeted by labor and greens.

In Person

Phil Radford: Last Call, Save the Ales.

BOOKS: Empire’s new clothes.

The Empty Theater

BOOKS: Joan Didion vs. the political class.

BOOKS: The Complete Works of Isaac Babel.

Ghost World

FILM: The Devil’s Backbone of the Spanish

Civil War.

|

December 22, 2001

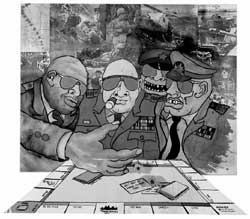

Where The Sun Never Sets

Empire, a collaboration between jailed Italian Communist Antonio Negri

and American literary theorist (and, one feels, junior partner) Michael Hardt,

is an attempt, probably the most fully realized to date, at a Marxist read on

globalization. Unlike many anti-globalizers, North and South, they vigorously

reject any suggestion that a return to the world of autonomous nation-states

is possible. They accept the new world order— with its global economy,

global culture and global police actions—as a given, and, taking the longest

of long views, seek out the new possibilities it opens up for human liberation. The book divides into three strands. The first is a new kind of global sovereignty,

replacing that of the nation-state. The second, and least interesting, is what

they take to be the economics of Empire, a highly conventional account of “globalization”

that could be excerpted comfortably in The Economist or Financial

Times. The third is the possibilities for resistance or revolution opened

up by the new order.

This vision is sketched out at a very high level of abstraction and seems rather

obviously contradicted by the reality of unchallenged U.S. supremacy that we

all read about in the papers. But Hardt and Negri rightly insist that the content

of a military intervention can’t always be settled by looking at the insignia

on the uniforms. While nation-states always acted, covertly or overtly, in their

own national interests, today’s interventionists, whether they know it

or not, are compelled to serve an incipient transnational order. The Gulf War was perhaps the first war of this kind. There the United States

found itself compelled to act “not as a function of its own national motives

but in the name of global right.” As Hardt and Negri don’t quite acknowledge,

all U.S. imperial wars, from the Spanish-American on, have been conducted “in

the name of global right.” But today, as they insist in one of the book’s

defining if not most original passages, rhetoric has become, or replaced, reality.

Hardt and Negri see the language of human-rights interventions not as cynical

window-dressing but as their real content: Police power is the signature of

Empire. And as in any well-run police state, police actions soon induce the

victims to police themselves, so the universal rights on which military interventions

are based are incorporated into national legislation everywhere. “Armies

and police anticipate the courts” in “an inversion of the conventional

order of constitutional logic.” What distinguishes this new situation from the old international order, dating

back to the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which effectively introduced the modern

nation-state, is that the internal affairs of states are no longer clearly marked

off as a sphere apart under international law. Once the principle is accepted

that interventions across borders are legitimate on human-rights grounds, a

system of global law has been acknowledged even if the bodies that will codify

and adjudicate it have not yet been formed. It’s not unfair to say that Hardt and Negri don’t present a single

piece of evidence for any of their claims. Empire is a book of visions,

not arguments. Either you accept them or you don’t. Still, isn’t there

something to it? If the logic of human-rights imperialism isn’t as profoundly

new as they would like, it remains a departure from the Cold War understanding

of international relations.

In opposition to Empire Hardt and Negri place “the multitude,” a

term carefully chosen and distinguished from “nation” or even “people,”

which are blinds for power. To speak of the will of the people, they insist,

is to postulate a uniformity that inevitably does violence to the aspirations

it supposedly embodies. The multitude is defined by its heterogeneity; it is

simply the many, the sum of numerous distinct human “singularities.”

The essence of political struggle is the effort of authority—whether capital,

nation-state or Empire—to assimilate this heterogeneity into a single will. Naturally, this rejection of traditional political identities —class as

firmly as nation—leads to a rejection of traditional political movements.

The struggles of oppressed peoples are, at best, progressive until they win

institutional form. Genet’s romantic attachment to the Palestinians as

history’s losers—“The day the Palestinians become a nation like

the other nations, I will no longer be there”—is paradigmatic. Similarly

for workers: “Against the common wisdom that the U.S. proletariat is weak

because of its low party and union representation,” they write, “perhaps

we should see it as strong for precisely those reasons. Working-class power

resides not in the representative institutions but in the antagonism and autonomy

of the workers themselves.” Don’t even get them started on meliorative state action like progressive

taxes or workplace regulation: The New Deal was an attempt to institute the

“factory society.” And today, in “imperial postmodernity,”

“big government has become merely the despotic means of domination and

the totalitarian production of subjectivity.” In short, the essential conflict

is not between nations or classes, but between the heterogeneous wills of human

singularities and any system that would, however benevolently, reduce them to

objects or instruments. Hardt and Negri trace the origins of this conflict to the Renaissance, when

people came to believe that the material world was not a reflection of divine

will but self-contained reality, and that individuals had the power to make

creative choices unconstrained by any prior or external law. Human beings were

unique, their choices fundamentally indeterminate. Spinoza was exemplary of

this sensibility. The old Spanish mystic is Empire’s hero because of his

refusal to acknowledge any constraints on this freedom, even physical survival:

“A free man thinks about nothing less than death,” they approvingly

quote. The logic here is tight: Spinoza’s assertion of human creative powers

requires his indifference to death, since death—and more generally the

desire for peace and security—is the weapon states use to “blackmail”

the multitude back into subordination. In a moment of brilliant condescension,

Stendhal once said that a peasant wants only two things: a warm winter coat

and not to be killed. On these terms a man’s a man; one is interchangeable

with another. In their sketch of the origins of the modern nation-state, Hardt

and Negri can’t conceal their impatience with the masses who, unlike Spinoza,

could not stop thinking about death and how to avoid it. Indifference to death is setting the bar for political virtue pretty high.

Combined with the sweeping dismissal of all the fundaments of the 19th and 20th

century left movements, one might suspect Empire of being just another

anti-political, end-of-history tract. This isn’t quite the case: Hardt

and Negri do advocate a sort of political judo, in which the logic of Empire

is turned against its masters. Empire is based on universal rights and the erosion

of national boundaries, they argue, so let’s assert the universal right

to cross boundaries, to migrate: “The general right to control its own

movement is the multitude’s ultimate demand for global citizenship.”

That is almost the only concrete demand put forward in the book. Though the master is hardly cited, Empire is a strictly Foucauldian

work. From the complexities of Foucault’s writing Hardt and Negri, like

many on the left, have extracted an unrelenting suspicion of any formal organization

or assertion of collective identity as only a more subtle form of domination.

Instead, “lateral connections” and “networks of relays”

must somehow replace democratic government and all other forms of delegated

authority. Hardt and Negri are right to warn against the spurious unities of

national or indigenous culture, but the Foucauldian lens constrains vision as

well as sharpens it. Empire has no place for organizations and leaders

that arise out of oppressed groups and exercise power on their behalf, including

trade unions, socialist politicians as well as problematic but undoubtedly progressive

organizations like the African National Congress or Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow

Coalition.

There is a real danger that by dismissing class as a basis for collective action,

Hardt and Negri are simply opening the way for an older set of identities based

on individualism and private privilege to go unchallenged. It’s worth remembering

that Negri made his political bones in the noontide of the ’60s, when the

great challenge was pushing up against the limits of social democracy and Keynesian

economics. Today, he is too quick to dismiss the possibilities of national economic

regulation. More generally, Empire’s focus on what has changed ignores all

the things that have not. One hundred and fifty years ago, Marx was already

appalled at the way capital converts unique human beings into interchangeable

instruments of production. But while this alienation may operate everywhere,

that doesn’t mean it has no center or source. Marx emphasized the importance

of looking behind the formal equality of the marketplace to relations within

the workplace, that zone of authority and subjugation that one may enter “only

on business.” Hardt and Negri by contrast make a conscious choice to limit

themselves to surfaces: “The depths of the modern world and its subterranean

passageways have in postmodernity all become superficial.” But never mind Marx. Empire is troubling on a more basic level. If Empire

has no center and no weak links, if any struggle has the capacity to “leap

vertically, to the virtual center of Empire,” then how does one distinguish

actions that matter from those that don’t? Hardt and Negri seem to be rejecting

the very idea of political strategy. One might conclude: Forget about strikes

and revolutions. The conversation in the coffeeshop, the day one calls in sick

from work, the evening’s sarcastic defiance of the anchorman, tonight’s

insurrectionary sex might just be the blow that brings Empire to its knees. There is no question that the secret of Empire’s success is its

denigration of traditional forms of collective politics (along with its contrarian

pro-Americanism). Rather than the “discipline of liberation,” they

valorize individual desertion, the Bartlebys who “would prefer not to.”

It is possible, I suppose, that everything has changed, and that the great political

projects of the 19th and 20th centuries are all dead. But Empire hardly makes

a convincing case for this. As the B-2s roar out of Whiteman, Missouri on their

global police actions, neither Empire nor Empire seems to offer much of a way

forward. J.W. Mason is a freelance writer in Amherst, Massachusetts. |

|