John Lewis’ Advice for Young Activists: March

In a new graphic memoir, the civil rights leader shows youth how to get in trouble--good trouble.

Sarah Jaffe

As the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom approaches, the spirit of protest seems to be rekindling in many parts of the country. The Dream Defenders remain camped out in the Florida capitol, demanding justice for Trayvon Martin and an end to racial profiling; North Carolina’s Moral Monday protesters have rallied and committed civil disobedience each week, defying the far-right agenda of their state legislators. In New York, the coalition against stop and frisk won its victory in court, but it took organizing, rallying, and yes, marching, to make it happen.

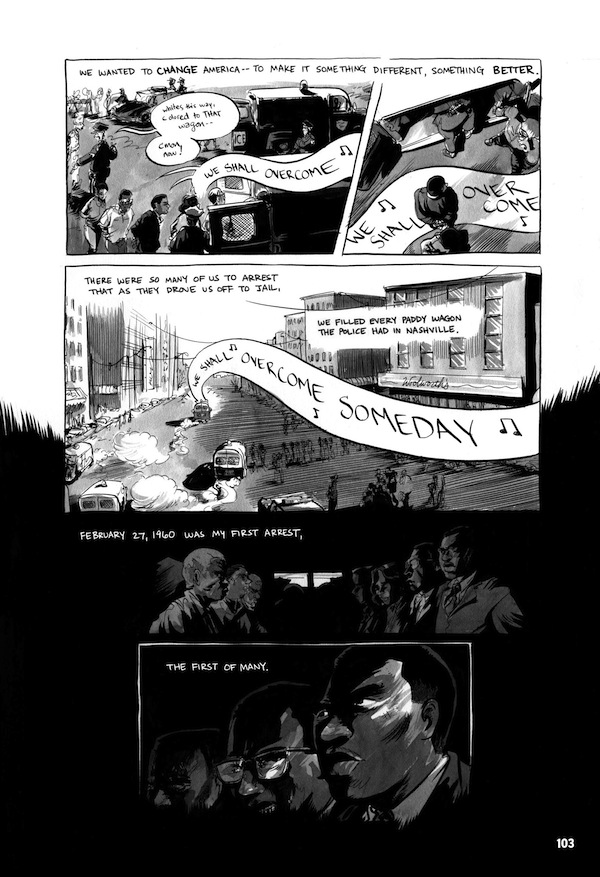

It’s a good time, then, for a new memoir by congressman and 1960s civil rights leader John Lewis. In March: Book One, out today from Top Shelf Productions, Lewis’ history and the highs and lows of the civil rights movement are brought to life — vividly, as the memoir is in comic format.

The first of three books follows a young Lewis from his family’s farm in Alabama to college and to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to lunch counter sit-ins, jail cells and a showdown with the mayor of Nashville. Co-written by Andrew Aydin, a staffer who’s been with Lewis for years, and drawn by award-winning comics artist Nate Powell, the book makes history feel real and present in a way that few accounts of civil rights legends have managed to.

Lewis and Aydin sat down with me during a visit to New York to discuss the new comic, their goal of inspiring and instructing a new generation, and where they’re finding hope these days.

Sarah Jaffe: This book is the first of three volumes, all with the title March. Why did you pick that title?

John Lewis: March is the spring, it’s life, it’s the beginning. So much happened in March. But it’s also moving feet.

Andrew Aydin: There was a quote that stuck with us very early on, it was something Dr. King said: “There’s no sound more powerful than the marching feet of the determined people.”

But March is so many different things. It is the need to march. It is March 7, 1965. There’s so much meaning behind it, it seemed almost self-evident.

Book 2 contains a very famous march. During the movement, the Congressman was so committed to action. There were so many moments where people wanted to talk, and he wanted to do. There’s this scene in Book 2, when they’re saying the violence is getting to be too much, we have to work out a solution, and they’d turn to John Lewis and say, “What do you think we should do?” And he would say, “We should just march.”

They would ask him again and he would say, “We should just march.” Finally they say, “John, everything you’re saying is that we should march, but people are going to get hurt, people are going to get killed, it’s your own foolish pride that’s getting involved with that, you’re just nothing but a sinner.”

And he’s like, “I may be a sinner, but we’re gonna march.”

It so typifies his view on how to get things done. We can sit around and talk about it, we can make speeches, but really when it comes down to it, the hard part is doing the work. Taking action.

John Lewis: This may sound a little self-serving here, but my own organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, objected to the march in Selma. We had an all-night discussion, a debate whether we should march. It’s clear to me that I should march. And I said, “I’ve been to Selma many many times, I’ve stood in line at the courthouse, I’ve been arrested, I’ve been to jail there. The local people want to march, and I’m going to march.”

So I jumped in the car with two of the young people, and I drove to Selma, late at night, got there at three or four in the morning, got our sleeping bags out, got up the next morning, got dressed, went to the church, and we lined up and we marched. The rest is history.

Sometimes you just have to do what your spirit says do. Go for it.

Why did you decide to do this as a comic?

Andrew Aydin: I was working for the Congressman on the 2008 campaign as his press secretary, and we started talking about what we were going to do after we had our nights and weekends back. I admitted I was going to a comic book convention — in politics that gets you laughs, snickers, a little jeering. But the Congressman said, “You know, there was a comic book during the movement and it was incredibly influential.” That comic book was “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story.”

I went home that night, Googled it, and read the story about how it inspired the Greensboro 4. I came back the next day and asked him “Why don’t you write a comic book?”

The Congressman looked at me like I was crazy there for a second, but we talked about the comic from the ’50s, and a couple weeks later I asked again, and the Congressman said, “OK, but only if you write it with me.”

It just seemed to make sense, the idea of a comic book inspiring young people to get involved and also teaching them the tactics.

The book uses President Obama’s inauguration as a framing device. Can you talk about the decision to do that?

John Lewis: People ask me from time to time whether the election of Barack Obama was the fulfillment of Martin Luther King’s dream, and I say, “No, it’s just a down payment.”

Because we’re not there. More and more, people are saying that we still have a distance to travel, and that we cannot be at peace or be at home with ourselves in America until we create a truly multiracial democratic society, where no one is left behind, and it doesn’t matter whether you’re black or white, Latino or Asian-American or Native America, whether you’re straight or gay. . And there’s a way to do it. If you want to change things, you got to find a way to make some noise. You cannot be quiet.

The lessons of March say, This is the way another generation did it, and you, too, can follow that path, studying the way of peace, love and nonviolence, and finding a way to get in the way. Finding a way to get in trouble — good trouble, necessary trouble.

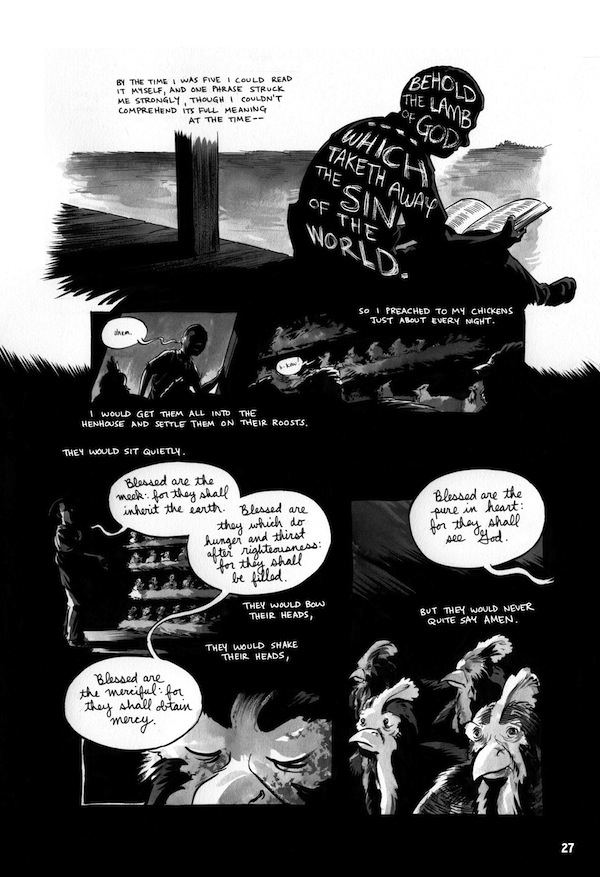

The book relates some of the experiences you had as a young person that led you to civil rights activism. Most people probably wouldn’t think of raising chickens as a thing that would shape a civil rights leader.

John Lewis: It may sound sort of silly, sort of strange, but I wouldn’t be the person I am today if it was not for those chickens.

It was my calling to take care of these innocent little creatures. I’m convinced those chickens that I preached to in the ’40s and the ’50s tended to listen to me much better than some of my colleagues listen to me today in the Congress. Really! Most of those chickens were a little more productive. At least they produce eggs.

They taught me discipline, they taught me patience, they taught me hard work and stick-to-it-ness.

You talk about Emmett Till’s death as a pivotal moment for you, and it seems like Trayvon Martin’s death has been a touchstone for a new generation of activists. Yet both of their deaths came at a time when violence against young black men was not rare. Why do you think each case hit a nerve?

John Lewis: I think there are certain periods in our history — just a spark.

I was 15 years old, working out in the field when I heard what happened. I kept thinking that it could happen to me, but especially to some of my cousins who lived in Buffalo, New York, who would come South in the summer to spend time with us.

A few months later, when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, one thing she said in later years was, “It’s not just my feet that were tired, but also, I thought about Emmett Till.” I remember that very, very well.

One of the things that the comic format does so well for this story is capture the violence and brutality that practitioners of nonviolence went through, both in preparation for and during actions. I particularly loved the sequence where one person quit training, saying it was too hard. Talk about the process of getting those moments on paper.

John Lewis: We provided the words, but [the artist] Nate Powell — I love his capacity to capture the drama, to bring it to life, to make it real. You can see it; you can feel it. Even though I lived through it, to see it there makes the words sing.

Andrew Aydin: This is very much centered around stories that I’ve heard the Congressman tell to all these people over the years. Nate lifted that off the paper and made it something at a whole other level. He’s very good at finding a natural flow for your eye.

We tried make sure that it wasn’t just accurate for the sake of telling the story, but accurate for the sake of instructing, so that people who have never been to a nonviolent workshop could read and understand what one was. Nate really captured that.

Another thing I think the book did well was capture the real work that went on behind the scenes. We’re so rarely shown how many years of preparation and organizing went into making movements happen. I’d love to hear about the challenges of showing that part of the story.

John Lewis: The planning, the training, the nitty-gritty organizing — you may wait for days or weeks or even months before you see something. But you do it. You’re consistent and you’re persistent, day in and day out.

Andrew Aydin: You see how this work ethic has just been such an omnipresent force in the Congressman’s life since he was 17, 18 years old — or even before that, on the farm. I remember at several points asking “What time did that take place?” and he’d be like “Oh, 5:00, 6:00 a.m.” And you realize these are college kids. How many college kids today get up at 5:00 in the morning, much less to go to an organizing meeting before class?

John Lewis: On April the 19, 1960, the attorney for the Nashville movement who had defended the students, his home was bombed around 6:00 a.m. And by 6:30 or 6:45 we were in a meeting. Students came from all over the city and we made a decision — it was a consensus — that we would have a march from the heart of the student community down to city hall. We sent the mayor of the city a telegram to meet us at high noon. There were more than 4,000 students saying, “Mr. Mayor, do you favor desegregation of the lunch counters?” And the next day, the banner headline in the local paper read that the Mayor said Yes to the integration of the lunch counters.

It was that sense that we had to act, we had to do something, we couldn’t wait.

Andrew Aydin: You always say, “You gotta get up! You can’t sleep through the revolution!”

The anniversary of the March on Washington is approaching quickly, and it’s never seemed more relevant in my lifetime. We’re seeing renewed attacks on civil rights and voting rights, along with a renewed movement for racial and economic justice. How are you feeling about the present day?

John Lewis: In spite of all the problems and difficulties, all the apparent setbacks, delays, I feel very hopeful, very optimistic. I think we are in the process of building a very powerful movement.

North Carolina’s governor just yesterday signed into law one of the most unbelievable pieces of legislation that would lead to a systematic, deliberate effort to suppress the votes of minorities, young people and the elderly. But in spite of that, I’m hopeful that we’re going to continue to push, and it’s going to start the fire for a real movement. Look at what’s happening in North Carolina now, the Moral Mondays. It’s a good sign. It’ll spread around, not just the South, but around America.

What do you hope that some of those young people involved in North Carolina, camping out in the capitol in Florida, what do you hope that they take away from this comic?

John Lewis: It’s my hope that many of the young people will have an opportunity to read March and be inspired, and see another generation got out there and did what they could, and that we too must pick up and push the ball further down the road.

Andrew Aydin: Some people have started getting advance copies, and one of them gave the book to his 9-year-old son.

John Lewis: It’s a white man, right?

Andrew Aydin: Yes. His kid read the book, enjoyed it, had a little trouble with Emmett Till’s death, but it resonated with him, and so now he’s put on a suit and is marching around his house demanding equality.

What does that say about what we have to look forward to?

John Lewis: They shall lead the way. Like the children in Birmingham and Selma, Albany, Georgia and other parts. They led the way.

Andrew Aydin: That’s part of the bigger message that I think we’ll really be able to get into after this book. Because the tactics that worked in Birmingham didn’t necessarily work in Albany, and they had to change. Tactics in one city didn’t work for every foe or every objective. From that original idea of the Montgomery bus boycott being useful as an example of successful nonviolent direct action, the whole premise is showing more and more examples of different tactics used to express different forms of opposition. As activists today look for new tactics to address their own opposition, they have inspiration and they see concrete examples of how things were reimagined but still stuck to the basic tenets, the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence.

Panels from March: Book One courtesy of Top Shelf Productions. All rights reserved.

Sarah Jaffe is a writer and reporter living in New Orleans and on the road. She is the author of Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion To Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone; Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt, and her latest book is From the Ashes: Grief and Revolution in a World on Fire, all from Bold Type Books. Her journalism covers the politics of power, from the workplace to the streets, and her writing has been published in The Nation, The Washington Post, The Guardian, The New Republic, the New York Review of Books, and many other outlets. She is a columnist at The Progressive and In These Times. She also co-hosts the Belabored podcast, with Michelle Chen, covering today’s labor movement, and Heart Reacts, with Craig Gent, an advice podcast for the collapse of late capitalism. Sarah has been a waitress, a bicycle mechanic, and a social media consultant, cleaned up trash and scooped ice cream and explained Soviet communism to middle schoolers. Journalism pays better than some of these. You can follow her on Twitter @sarahljaffe.