|

August 21, 2000 Features What's

in Your Green Tea? Why

I'm Voting for Nader ... ...

And Why I'm Not Fox

Shocks the World Tijuana

Troubles Unions

Get Religion News Safety

Last Sale

of the Century Water

Wars Profile Editorial Viewpoint Appall-O-Meter Give

It Away Good

Fela Time's

Arrow Mission:

Impossible 3 |

... And Why I'm Not

By James Weinstein

In 1948, when I cast my first vote for president, Henry A. Wallace, vice president during FDR's second and third terms, was running as the Progressive Party candidate against Republican Thomas Dewey and Democrat Harry S Truman. In August, he was at 12 percent in the polls. On election day, he got 2 percent. My history professor at Cornell, a wonderful man named Paul Wallace Gates, was the New York state treasurer of the

|

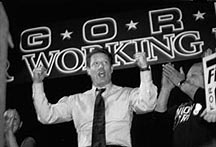

| Credit: Joeff Davis |

Wallace for President Committee. On election day, he voted for Truman. Within a year the Progressive Party disintegrated.

In 1980, Barry Commoner ran as the Citizens Party candidate for president against Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. Progressives worked hard and got him on the ballot in 29 states. He got only 220,000 votes and the Citizens Party quickly disappeared. Now it's Ralph Nader's turn, and his supporters repeat the identical arguments and exhibit the same enthusiasm for Nader that I did for Wallace and others did for Commoner. Sadly, there is no reason to expect that the results will not be the same.

Bob McChesney says that we have to think in broader terms than the immediate election, a statement with which I fervently agree. But he sees the Nader campaign as a necessary step in building a progressive political movement that will amount to more than a hill of beans. There, I believe, he is dead wrong.

First, serious politics requires participation in elections on all levels of government and at all times. Organized popular constituencies don't come from the single-issue movements that McChesney sees as Nader's base. These single-issue movements focus narrowly on their issues and operate by putting pressure on legislators to support or oppose specific legislation or

| Read Robert W. McChesney's article, "Why I'm Voting for Ralph," |

policies. Broad electoral constituencies, on the other hand, must be created by common popular action around a program that embodies shared universal principles. The Nader campaign did not arise from such a movement, nor is it organized in a way that will produce one. It has sprung forth out of nowhere. It represents no identifiable constituency. Like others on the left, Nader and his disparate supporters are simply following a well-established pattern. Every four or eight years, some of us look around and are so appalled by the major party choices that we are compelled to tilt at windmills by engaging in quixotic campaigns for president.

This campaign follows that pattern. It started at the top and it will end at the top. In part, it will because Nader is acting purely as an inspired individual. He is a talking head without a political body. True, he is using the Green Party in some states as a framework for his campaign, but without him there would be no campaign because neither he nor they represent a movement experienced in building broad electoral constituencies.

Second, few people outside the circle of true believers, and a couple of union leaders who appear to be using Nader as leverage to get favors from Clinton or Gore, will ever see him or hear his message. In 1980, after spending most of their money on efforts to get on the ballot, the Citizens Party could afford only one national radio broadcast during the campaign. In it, Commoner said something about Reagan and Carter's "bullshit." The next day, the New York Times reported, "Presidential candidate says 'bullshit.' " On election day that was all the general public had heard or knew about Commoner and his party. Today, Nader is getting more media coverage, but it is horse-race reporting; his ideas remain as invisible to the general public as Commoner's.

Jesse Jackson, on the other hand, did what McChesney denigrates: He ran in the Democratic primaries in 1988. As a result, he participated in the televised debates, outshone his rivals and made the most enthusiastically received

| Tell us what you think about Gore vs. Nader. |

speech at the Democratic National Convention. His ideas received wide public exposure. And thus he greatly increased the political visibility of the African-American community, as well as his own clout within national politics. He created a potential for a sustained left movement, though unfortunately he did not pursue that goal.

McChesney also argues that the difficulties posed by a grassroots challenge within the Democratic Party are too great to overcome; he says the requirement for "obscenely massive campaign war chests," and the "tight noose of the corporate news media with their pathetic range of legitimate debate" make progressive participation within that framework impractical. But the same difficulties are infinitely greater for those operating as a third party. In fact, Jackson got considerable media attention precisely because he was in the primaries. He was able to put forward his ideas in nationally televised debates at no cost to his campaign. He needed only a small fraction of the money Nader will have to raise if he hopes to receive half as much media attention as Jackson did.

Instead of looking at this realistically, McChesney resorts to wishful thinking about Nader being given a place in the nationally televised debates. "If there is justice," he writes, "and [Nader] gets a place in the presidential debates, his support almost certainly would climb dramatically." Duh! Of course, that's why Jackson ran in the Democratic primaries.

Third, McChesney suggests that by speaking with authority in plain language about power, fairness, justice and democracy, Nader can unify the masses in opposition to the two corporate candidates. But the issue here is not the value of Nader's ideas and principles. Rather it is two-fold: first, whether these ideas will be heard and examined, and, second, given the potential for taking votes away from Gore, what effect this would have on the left's natural constituencies.

In a recent article urging people to vote for Nader in Conscious Choice, an ecology magazine, Dan Hamburg explains the dilemma that many sympathetic to Nader's ideas will face. In states where the Democrat or Republican is way ahead in the polls, people should vote for Nader, he says; while in states where Bush and Gore are neck-and-neck, those not wanting to elect Bush should vote for Gore. But following this advice would negatively affect Nader's vote, especially in the states where he now is polling best. The result, among other things, would be to understate the degree of popular agreement with Nader's ideas and thereby further marginalize him and the left.

McChesney clearly rejects Hamburg's approach, but his path might mean that a vote for Nader would win a state, and possibly the presidency, for Bush. This appears to be the case in Michigan, for example, where Nader is presently polling 8 percent - enough to throw the state to Bush as things now stand.

Well, Naderites would say, what's wrong with that? And the answer is that besides electing Bush, there would also be hell to pay with the very social base - labor and African-Americans - that is most favorably disposed to Nader's ideas, and is the left's natural constituency. The problem is that these are the people most loyal to the Democratic Party. Gore will get 90 percent of the black vote, and 60 to 65 percent of labor's vote. Both constituencies have practical reasons for wanting a Democratic president. To them, Nader is OK, but only as long as he is not a spoiler. Hamburg indicates that the same is true among environmentalists.

In short, the issue here is not whether we need a second force in American politics - one that would represent the interests of the overwhelming majority of men and women who work for a living. There's no dispute on this. But for us to realize this goal, we have to understand the structural nature of our political system and how to use it. Otherwise, we will remain little more than

| Read other responses to our Gore vs. Nader coverage. |

gadflies. Consider this: No significant third party in American history, with the exception of the old Socialist Party, ever ran more than two consecutive presidential campaigns. And, again except for the Socialists, the second campaign of the third parties has always been much weaker than the first. The Socialists ran five campaigns between 1900 and 1920 and remained an important voice in American life until their breakup three years after the Russian Revolution. But even at the height of their influence they had no potential of becoming a major presence in Congress, much less of electing a president.

The reason for this is that we do not have a system in which the members of an elected parliament select the prime minister as head of government; nor do we have a system of proportional representation for electing legislators. In countries with either of those systems, minority parties often have a chance to participate meaningfully in the legislature, and even, in coalitions, choosing the prime minister.

But in a system like ours, where the president is elected directly and Congress is elected in single-member majority districts, the system moves inexorably toward two parties. Only in periods when one of the major parties is fatally wounded over an issue of vital national concern - as was the case with the Whigs and the extension of slavery in the 1850s - has it been possible for a third party to enter the scene and grow rapidly. That, of course, is how Lincoln won on his party's second try.

But all is not lost. When Harold Washington was mayor of Chicago, he used to talk about the city's two parties. He didn't mean the Democrats and the Republicans; he meant his party and little Richie Daley's. Like both major parties throughout the country, the official party was open by law to anyone who registered in it. Indeed, anyone can enter a primary for legislative or executive office. And any group can promote its own candidates and thereby become a force in national politics, as the Christian right did in the Republican Party in the '80s. Furthermore, because only a small fraction of the electorate votes in primaries, a well-organized force can win nominations much more easily in primaries than in general elections.

Rather than panicking every four years, getting all wound up in an essentially

hopeless campaign, and then, when the results are disappointing, lapsing

into disillusionment and inertia, the left should begin thinking seriously

about how to intervene successfully in our political system. It's time

for us to confront reality and to grow up politically. ![]()

James Weinstein is the founding editor and publisher of In These Times.

|

In These Times ©

2000

Vol. 24, No. 19 |

Election 2000 Coverage

Never

Mind the Bollocks

BY BILL

BOISVERT

Here's

the new Republican Party

September

4 , 2000

The

Battle of Philadelphia

BY DAVE LINDORFF

September

4 , 2000

Working

It

BY DAVID MOBERG

Will unions go all out for Gore?

September

4 , 2000

Editorial

BY DAVID MOBERG

Big money problems.

September

4 , 2000

Cleaning

Up

BY HANS JOHNSON

Missouri, Oregon consider campaign finance initiatives

September

4 , 2000

Why

I'm Voting for Nader ...

BY ROBERT McCHESNEY

August 21,

2000

...

And Why I'm Not

BY JAMES WEINSTEIN

August 21,

2000

Dumped

BY JEFFREY ST. CLAIR

August 7,

2000

Bush's

dirty politics turn an Texas town into a sewer.

An

Environmental President

BY GUY SAPERSTEIN

August 7,

2000

Three's

Company

BY JOHN NICHOLS

July 10, 2000

Third parties strategize for the November elections.

Editorial

BY JOEL BLEIFUSS

June 12, 2000

Memo to third parties: Face Reality.

Marching

On

BY DAVE LINDORFF

June 12, 2000

Unity 2000 plans to disrupt this summer's GOP convention

Party

Palace

BY NATHANIEL HELLER

May 1, 2000

George W. Bush's lucrative sleepovers

Stupid

Tuesday

BY HANS JOHNSON

April 17, 2000

After Super Tuesday,

progressives mull over missed opportunities

What

Women Want

BY DAVID MOBERG

April 17, 2000

Working women's votes

could seal Al Gore's fate. But is he listening to them?

David

vs. Goliath

BY KARI LYDERSEN

April 17, 2000

Socialist presidential

candidate David McReynolds

How

to Deal with Gore

BY JEFFREY ST. CLAIR

and LOIS GIBBS

April 17, 2000

Love him or leave him?

Ralph

Really Runs

BY DOUG IRELAND

April 3, 2000

Nader kicks off his

second bid for president

Editorial

March 20, 2000

Flub watch.

On

the Fence

BY MATTHEW KNOESTER

March 20, 2000

Human rights or big oil for Al Gore?

The

First Stone

BY JOEL BLEIFUSS

March 6, 2000

Vanishing voters.

Gush

vs. Bore

BY DOUG IRELAND

March 6, 2000

Free

Ride

BY PAT MURPHY

March 6, 2000

Meet the real John McCain.

Cash and

Carry

BY JEFFREY ST. CLAIR

March 6, 2000

George W. Bush's environmental menace.

Fair

Weather Friends

BY JUAN GONZALEZ

March 6, 2000

Candidates court the Latino vote.

More

Marketplace Medicine

BY DAVID MOBERG

March 6, 2000

Neither Democrats' health plan will fix the system.

New

Labor, Old Politics

BY DAVID MOBERG

November 14, 1999

Bradley

Courts the Black Vote

BY SALIM MUWAKKIL

October 31, 1999

Changing

Primary Colors

BY DAVID DYSSEGAARD KALLICK

June 13, 1999

The

Great Right Hope

BY RUSSELL CONTRERAS

Who is George W. Bush?

May 30, 1999

Money

Money Money!

BY NEIL SWANSON

Al Gore and Bill Bradley go one-on-one.

May 30, 1999