Drain the Metaphor: Why the Media Needs to Rethink the Way It Talks About Swamps

Emeline Posner

“Drain the swamp,” Trump’s anti-corruption rallying cry on the campaign trail, has itself been drained of any strength it once carried. Its deflation began even before the inauguration, when the president-elect began assembling a cabinet that consisted of the very figures he’d promised to oust: lobbyists, bankers, businessmen and career politicians. The media, however, continues to sustain the empty metaphor.

Political inaccuracies aside, the language perpetuates a dangerous and deep-seated misperception that wetlands are impediments to development and progress.

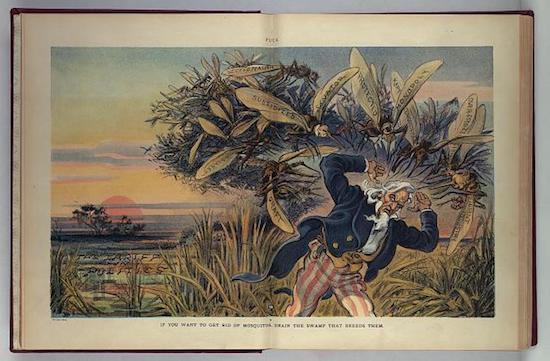

Trump was not the first politician to invoke swampland as a stand-in for an undesirable feature of American politics. Socialist Rep. Victor Berger (S. Wisc.), used “swamp” as a surrogate for the capitalist system in 1907, writing in an essay: “We should have to drain the swamp — change the capitalist system — if we want to get rid of those mosquitos [capitalist speculators].” Ronald Reagan revived the metaphor in the 1980s to critique Big Government and, in 2006, Nancy Pelosi used it to criticize lobbyist influence in the GOP-dominated House.

But as Republicans renew their efforts to roll back both state and federal protections for wetlands, the most recent resurgence of swampland metaphor in our national discourse has grown increasingly troubling.

A recent Politico headline asks, “Has Trump drained the swamp in Washington?” The lede in a Post article begins, “Less than a year after President Trump rode into town promising to purge Washington of corrupt insider dealing and profiteering, the swamp seems as fetid as ever.” The list goes on — an op-ed in the Times entitled, “Trump made the swamp worse. Here’s how to drain it,” adds to the ubiquity of similarly themed articles in the New Yorker, The Atlantic, as well as even more mainstream sites like Newsweek, NBC and ABC. But even leftist publications, like The Nation, Salon, Truthout (and even In These Times), despite devoted coverage of environmental issues, write negative connotations of wetlands into their pages.

This is problematic.

As ecologists have written for decades, swamps and their wetland kin — fens, bogs, standing pools and marshes — are invaluable ecosystems. They filter water, absorb floodwaters, store carbon and provide habitats for innumerable plant and animal species, including endangered migratory birds like whooping cranes and trumpeter swans.

Wetland drainage can be devastating on many levels. As ecologist Adam Rosenblatt pointed out in an op-ed last year, the extensive draining of the Everglades resulted in fires ravaging thousands of acres for years, soil nutrient depletion, groundwater depletion and the intrusion of saltwater into South Florida’s aquifer. Restoration efforts, begun in earnest in 2000, will take at least 30 years and will cost an estimated $7.8 billion.

But you would never learn this from the media.

Last fall, for Slate, writer John Kelly dove into the political history of the metaphor — and its ties to early 20th century socialism — but neglected to mention at any point in the article that swamp draining is ecologically devastating. (He was moved enough, however, to offer a sardonic correction to Trump’s language about swamp draining: “You can’t drain a swamp like you empty a bath,” writes Kelly, “You have to build special ditches and canals that redirect the water. But knowing that would require doing a little bit of homework.”) Another “explainer” piece, to which Kelly links, lists the many permits and environmental studies that would be required for Trump to drain wetland areas in the capital. But only at the end of the piece does the author offer a brief “bonus explainer” on why the practice of swamp draining is misguided. The reminder reads:

Is draining a swamp a good idea? No. While swamps have a negative connotation, that is largely due to our misunderstanding of their ecological use. Swamps play a hugely important role in the ecosystem. They help prevent erosion, they’re able to hold excess water to help prevent flooding, they help filter out pollution, they provide fish nurseries, and they provide habitats for more than one-third of all endangered species. It wasn’t until partway through the 20th century that ecologists began to understand these benefits. Once they did, the pace of swamp drainage in the United States slowed down considerably.

Some might argue that the media’s engagement with political swamp metaphor, though unfortunate, is unlikely to have a tangible impact on wetland conservation efforts. (Breitbart made a similar argument in a snide response to Adam Rosenblatt’s op-ed.) But as the current administration’s attack on wetlands continues, the media’s language may be helping to skew the dialogue around conservation and environmental regulation toward Republican interests.

As Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator Scott Pruitt travels around the country meeting with Republicans about water regulations, Republican legislators are working to repeal the Clean Water Rule (CWR). This Obama-era regulation, still under litigation, would expand federal protections for isolated wetlands and streams under the authority of the EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — protections that had existed in unclear legal territory for decades due to murky language in the 1972 Clean Waters Act.

Unsurprisingly, Trump would benefit personally from this repeal.

The CWR would raise waterway maintenance costs for golf course owners, who are among the biggest offenders when it comes to wetland disturbances. The Trump organization has been cited previously for wetland disturbances at the site of a golf course in Bedminster, N.J. According to Bloomberg, 20 Trump Organization employees are members of the National Golf Association — an organization that spent $30,000 lobbying against the CWR when it was being written in 2015.

Should the legislation be repealed, more than 20 million acres of isolated wetlands would have their federal protections rescinded, making them more vulnerable to drainage, disturbance and filling. And if regulation of these wetlands falls back to state control, then we might see a lot more of the shenanigans announced in Wisconsin this summer: a legislative package from its Republican administration offering large tech development exemptions from wetland disturbance regulations.

Also in Wisconsin, Republican legislators are pushing a pair of bills that environmentalists are calling the “end game” for development in wetland areas. The bills, SB600 and AB547, would remove state protections for all wetlands not protected on the federal level by eliminating the permit application process overseen by the state’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) altogether.

If passed, these bills would immediately open up as many as one million acres of wetlands, or one-fifth of Wisconsin’s total wetland acreage, to drainage, filling and disturbance. (Residents and conservationists voiced concerns to the bills’ coauthors, Assembly Majority Leader Jim Steineke and Sen. Roger Roth, at a public hearing last week, but it is not clear whether this will have any impact on the bill.)

This attempt to roll back state-level wetlands protections in Wisconsin is egregious, but politicians in Republican-dominated states have been pushing back against necessary environmental regulations for years. And under the new administration, Republican lawmakers are slowly growing more confident. Earlier this year, legislators in South Carolina introduced a bill that would eliminate public hearings when developers or farmers submit plans to disturb wetland areas.

Even on the federal level, the current permitting process for developing land on or near protected wetlands is not enough to hold developers accountable.

If a developer insists that wetland disturbance is “unavoidable,” the Army Corps of Engineers offers permits allowing draining or filling on the condition that the developers invest double the disturbed acreage in a wetland mitigation bank. But as many point out, for unique ecosystems, for instance tamarack bogs, which form over thousands of years, mitigation is not always an adequate exchange for wetland drainage. And to add insult to injury, it’s unclear how many developers satisfy these mitigation requirements.

A 2015 report showed that, in the greater Houston area, the Army Corps of Engineers had no tracking system in place. The report found “little or no evidence of compliance” for half the permits reviewed in eight counties around Houston. But federal agencies aren’t going to receive the proper staff and proper budget they need to be able to oversee the permitting process with care, transparency and efficiency. At least not under Pruitt, who has just announced that the reigning champion of weakening state regulations — none other than Cathy Stepp, the former secretary of Wisconsin’s DNR — will be heading the EPA’s Region 5 offices.

The current Republican assault on wetland protections, and on the agencies that help to regulate wetlands, will only continue to grow in scale on the state and federal levels. While they wage this quiet war, it is imperative that the media reconsider the way in which it talks about swampland.

When writers engage with wetlands on the terms set by people like Trump or Walker — politicians who have ideological agendas to implement and profits to make from draining actual swamps and thereby creating land that can be opened to commercial development — they not only predispose people to feel ambivalence toward wetland ecosystems, they skew the larger dialogue toward Republican interests.

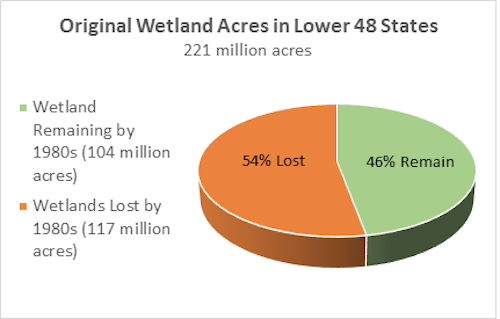

In fact, few Americans have any exposure to wetlands, because few such regions remain. The 20 million acres of wetlands that may lose their federal protections are nothing in comparison with the approximately 110 million acres that were already drained by the 1980s. Meanwhile, a conservative estimate puts the total number of wetlands in America at around 50 percent of the original pre-settlement total. In agricultural states like Indiana and Illinois, that number is closer to 15 percent. Those that do remain are increasingly concentrated in wetland mitigation sites, predominantly in rural, sparsely populated areas.

But while many Americans may not be interacting with wetlands on a daily basis, most Americans, myself included, do read the media every day. Every time “drain the swamp” appears in a headline or in a lede, it desensitizes readers to the importance of wetland ecosystems and strengthens, even if indirectly, Republican arguments against wetland regulation.

It’s time the media finally reconsiders its use of a well-worn metaphor and assumes responsibility for providing critical ecological information. There is no swamp in Washington, D.C., or anywhere in the United States, that needs to be drained — but there is a pile of politicians who stand to profit from convincing Americans that there is.