Chicago Is Spending $1.6 Billion on 13,000 Police. Is It Worth It?

With shootings and murders on the rise, community organizers and criminologists point to a police hiring spree from just four years ago to show that more cops on Chicago’s streets aren’t the answer.

Carlos Ballesteros

Asiaha Butler walked into the Ellis Park fieldhouse on Chicago’s South Side for a community meeting on the Saturday before the Fourth of July. She was hoping to hear something different from local officials about their plans for improving public safety.

Earlier that afternoon, 1-year-old Sincere Gaston died after being shot in the chest as he sat in the backseat of his mom’s red sedan on their way home from a laundromat in the city’s Englewood neighborhood, also on the South Side. So far in 2020, 43 people have been murdered in the Englewood and West Englewood communities, a higher homicide count than in the entire city of Oakland, California.

“Every murder, every shooting hurts,” Butler said. “There’s no getting used to this.”

As head of the Resident Association of Greater Englewood, Butler, 44, was invited to the fieldhouse by city officials to figure out, alongside prominent local clergy and other community leaders, how to stem the carnage they all feared for the upcoming holiday weekend.

Butler attended a similar meeting in 2016, the city’s worst year for gun violence in nearly two decades. It didn’t take long for Butler to realize that this year’s meeting started to sound like a rerun.

“I’m looking around this room and these are the same leaders as last time, talking about the same ideas, and the city proposing the exact same strategy: More police on the street,” she said. “And guess what? Fourth of July was just as deadly.”

With more than 400 murders so far this year, Chicago is on track to surpass its 2016 homicide rate.

At the time, Mayor Rahm Emanuel responded by hiring over 1,000 new cops over two years. The estimated cost in salaries, benefits and supervision for the new hires was more than $130 million in the first year, or well over $1 billion in their first decade on the force. Emanuel’s administration defended the costly hiring spree by citing an alleged “top to bottom” analysis of the police department showing that the city needed hundreds of new cops.

But four years later, attorneys for the city say that staffing analysis is nowhere to be found.

Today, Chicago has more sworn officers per capita than New York, Los Angeles and Houston. Salaries and overtime pay for those officers take up almost all of the $1.65 billion earmarked for the police department in the city’s 2020 operating budget, the largest police budget on record.

“We hired all these new cops and for what? It feels like we’re back to square one,” Butler said.

In a statement, Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s office said Chicago is committed to addressing the root causes of gun violence beyond policing. The mayor’s office touted the Invest South/West initiative, which aims to bring $750 million to ten distressed neighborhoods over the next three years. Lightfoot’s office also highlighted the city’s “record-high investments in street outreach and trauma-informed victims services.”

But as the city faces an expected $700 million budget shortfall due to the coronavirus pandemic, criminologists say more police officers doesn’t necessarily mean less crime. And a growing cadre of activists and community organizers are urging Mayor Lightfoot to divest from the Chicago Police Department so that the city can afford to try something new.

‘Good and reasonable search’

When Emanuel took the podium at Malcolm X College on Sept. 22, 2016, Chicago had already surpassed 500 murders for the year and was averaging 12 shootings a day — levels of gun violence the city hadn’t seen since the mid-1990s.

With news cameras rolling, Emanuel outlined his plan to stop the bloodshed: The city would expand its mentorship programs, continue to fund summer youth jobs, and hire an extra 516 officers, 92 field-training officers, 200 detectives, 112 sergeants, and 50 lieutenants in two years.

“As big a problem as gun violence is for Chicago, it is not beyond our ability to solve. Ending this string of tragedies is our top priority as a city,” Emanuel said at Malcolm X. “We are infusing our police department with the manpower, technology and training to meet this challenge head-on.”

The new hires would reverse the shrinking of the department that had taken place during Emanuel’s first term in office, when, in the face of a $500 million budget deficit, he allowed the number of sworn officers to dip below 12,000 for the first time since the mid-1980s.

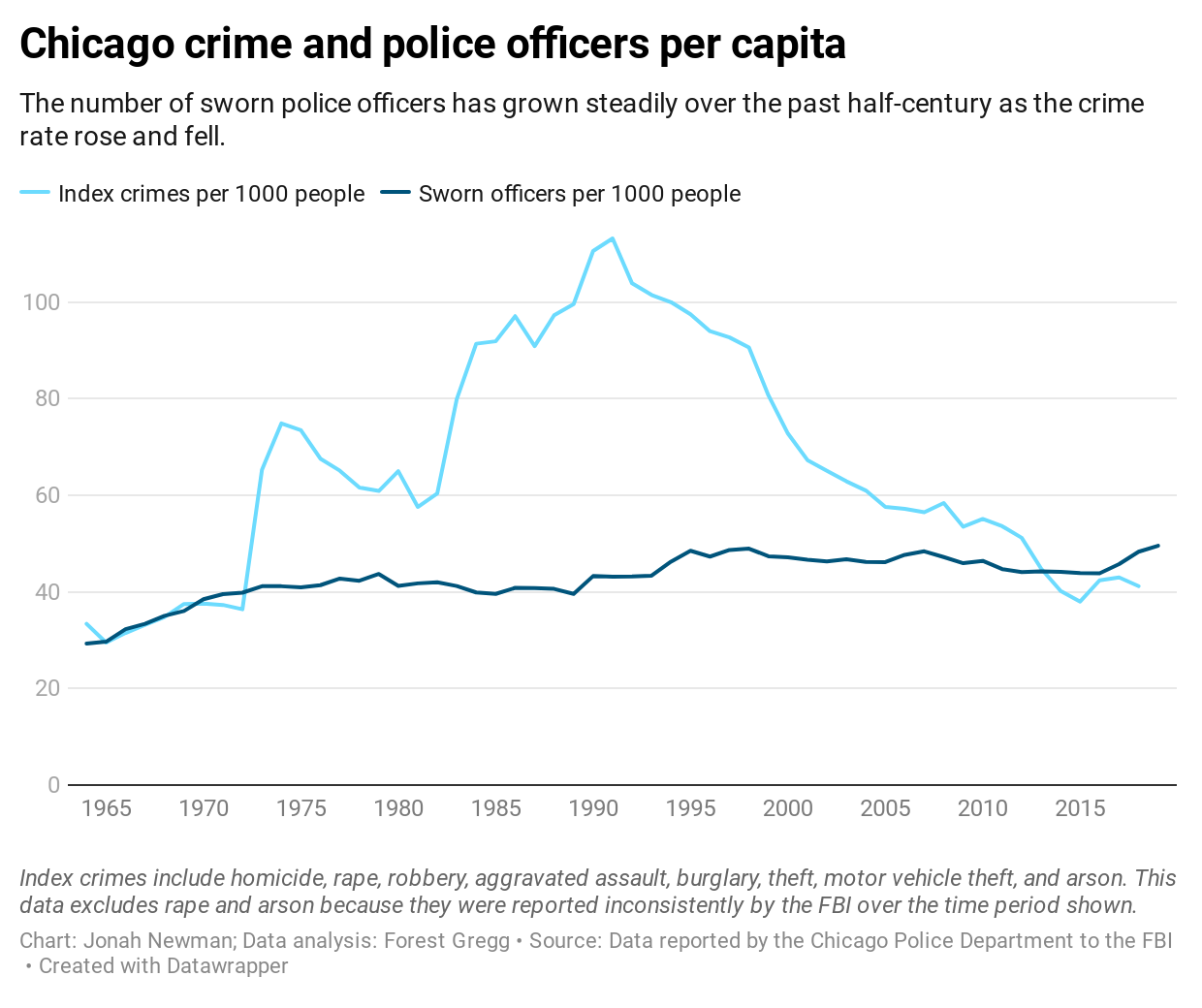

But as the number of cops fell, so did crime: Between 2011 and 2015, the number of index crimes — which include murder, robbery, aggravated assault, arson, burglary, and motor vehicle theft — dropped by 30%, according to an Injustice Watch analysis of CPD data reported to the FBI. (This analysis excludes rapes and sexual offenses.)

When asked by the Chicago Sun-Times why the city needed so many new cops, then-Supt. Eddie Johnson said Emanuel based his decision on a staffing analysis of the police department.

“We did an overall analysis of the department … and this is what I think we need to make Chicago safer,” Johnson told the newspaper a day before Emanuel’s speech at Malcolm X.

The police department has yet to release a copy of the staffing analysis.

“They’ve so far refused to hand over or simply can’t find any analysis they did to support that hiring,” said Tracy Siska, director of the Chicago Justice Project, a watchdog group that sued the department for not complying with a Freedom of Information Act request for the analysis.

Court records show the city first said the staffing analysis was part of a more extensive report on the police department conducted by an outside law firm. The city argued that the report — and everything in it — should be off-limits to the public because of attorney-client privilege.

But last December, Cook County Circuit Court Judge Caroline Moreland reviewed that report and didn’t find the missing staffing analysis, court records show.

Earlier this month, after conducting a “good faith and reasonable search,” the city said in court that it couldn’t find the staffing analysis within the police department’s files.

“The police department has a burden and an obligation to produce these records and it hasn’t,” said attorney Merrick Wayne of Loevy and Loevy, who represents the Chicago Justice Project.

A spokesman for the Chicago Police Department said the department determines its staffing levels based on “operational needs as well as keeping up with attrition levels.” But without being privy to the reasoning behind the department’s decision-making, Chicago could be spending a lot more on policing than it needs to, Siska said.

“Staffing decisions around policing are incredibly expensive, and need to be done based on science, not politics,” he said. “Just imagine what can be done on the South and West sides with $1 billion invested over 10 years.”

The Chicago Police Department is currently conducting a new staffing analysis as part of the consent decree it entered into with the Illinois Attorney General’s office last year. According to a June report from Margarey Hickey, the court-appointed independent monitor, the department has hired the University of Chicago Crime Lab, the Civic Consulting Alliance and other experts to perform the analysis. The report does not indicate when the analysis will be completed.

‘Deep interventions’

This year’s murder spike has some officials again calling for a greater police presence in Chicago.

Earlier this month, Superintendent David Brown nearly doubled the Summer Patrol Unit, which oversees so-called crime “hotspots” across the city, to more than 200 officers and deployed the department’s Community Safety Team, made up of about 300 officers, to areas of the South and West sides that have seen an uptick in crime. Brown also created an entirely new unit of 250 officers called the Critical Incident Response Team to act as, in his words, a “roving strike force” when needed.

City Council member Chris Taliaferro, a former cop and chair of the council’s public safety committee, wants the department to resurrect “Operation Impact Zone,” a controversial program disbanded in 2016 that placed foot patrols of young officers in high-crime areas.

Meanwhile, John Catanzara, Jr., president of Chicago’s Fraternal Order of Police, the city’s rank-and-file police union, went so far as to request that President Donald Trump send federal law enforcement to rein in “the chaos currently affecting our city.”

Trump eventually did send hundreds of FBI, DEA and ATF agents to Chicago in late July — reportedly with Lightfoot’s blessing. “What we will receive is resources that are going to plug into the existing federal agencies that we work with on a regular basis to help manage and suppress violent crime in our city,” the mayor told reporters last week.

But activists calling on Lightfoot to defund the police say more cops on the street isn’t an answer to gun violence. They point to a recent mass shooting in Auburn Gresham, where 15 people were shot outside a funeral home — even though there were two police squad cars and a full tactical team guarding the funeral.

“That the police were present near the funeral breaks some of the myths people have of what policing is, what it does, and what it can do. It’s evidence that more police are not going to prevent these shootings,” said Damon Williams, 27, co-founder of the activist group #LetUsBreathe Collective, and an Auburn Gresham native.

Instead of more police funding, Williams argues solving Chicago’s gun violence crisis will take years of investments in social services like job training and mental health counseling.

“When I hear of someone shooting up a funeral, I think of PTSD, depression, loss of jobs,” he said. “We’re not going to arrest our way out of this problem.”

Butler likes to refer to these kinds of investments as “deep interventions”: Long-term commitments to struggling neighborhoods beyond punishment and incarceration.

In Englewood—after decades of the city tearing down thousands of homes, schools, and department stores without putting anything in their place—that means literally building parts of the neighborhood from the ground up, she said.

“We need to help homeowners secure their homes, initiatives to get people working on restoring and filling abandoned buildings. We need to build new housing,” she said.

Funding for those ideas should come out of the police department’s coffers, according to Louisa Manske, policy director at the Workers Center for Racial Justice in Bronzeville and lead author of a proposal calling for Chicago to cut its police budget by $900 million within three years.

The cuts would bring the city’s per capita spending on policing, currently at more than $600 per resident, “just under the current average spent among the nation’s top ten most populous cities,” according to the proposal.

The city could reinvest most of that money — $700 million — into housing, public health and family and support services under the proposal. The rest would establish a “Community Safety Unit” focused on emergencies that don’t require police and take up the bulk of 911 calls like mental health crises, traffic incidents and filing crime incident reports.

“Three years might seem drastic,” Manske said, “but the city is in a state of emergency.”

A more gradual approach to defunding the police could be to replace sworn officers who spend most of their day at a desk with non-deputized civilians.

“It’s a lot cheaper to hire and train civilians to do those jobs,” said Wesley Skogan, a Northwestern University criminologist and an expert on the Chicago Police Department.

The city could also stop hiring new police officers as older ones retire. “Within 10 years, you’d cut the department in half,” Skogan said. “You can use that pot of money to jumpstart other programs that take responsibilities away from the police every year.”

John Hagedorn, a University of Illinois at Chicago criminologist and an expert on gang violence, said the city needs new, innovative solutions to address gun violence away from policing.

“The standard answer is that when you have a rise in crime, you should hire more cops, but the idea that more cops will mean fewer crimes is an old way of thinking,” he said.

“There’s no data that supports that.”

An either/or proposition?

Unlike mayors in cities like Minneapolis, Seattle and Los Angeles, Lightfoot isn’t interested in defunding the police, deriding the movement as simply “a nice hashtag.”

One of Lightfoot’s main arguments against the movement is that reducing the police department’s size would worsen job prospects for Blacks and Latinx people.

“When you’re talking about defunding the police, you’re talking about…eliminating one of the few tools that the city has to create middle-class incomes for Black and Brown folks. Nobody talks about that in the discussion to defund the police,” Lightfoot told The New York Times in June.

Lightfoot also argues Chicago can keep the police budget intact while also upping the funding for social services. “The investments that we are committed to making in violence reduction, in mental health, in affordable housing and workforce development; we need to make those investments, period, and we’ve committed to that,” Lightfoot told reporters in June.

“For me, it’s not an either/or proposition.”

But Manske said Chicago could hire Black and Latinx residents to fill the jobs created by shifting responsibilities away from police. “It’s an indictment on this city that one of the few options to achieve middle-class status is for Black and Latinx people to join the police. That should be an incentive for us to invest in other areas, not a reason to keep doing what we’re doing,” she said.

Activists say Lightfoot’s attempt to keep funding the police department at its current levels while raising money for more social programs is a non-starter.

“We don’t want [Lightfoot] to do both, because the police take up so much of our city’s budget and also perpetrate violence in our communities,” said Destiny Harris, a 19-year-old organizer with activist groups #NoCopAcademy and Dissenters, who grew up in the West Side neighborhood of Austin.

“If we keep pouring money into the police instead of things that address the root causes of violence,” she said, “we’re going to keep getting the same results.”

This story was produced in partnership with Injustice Watch.