Food, safety, modernization — all good words. But the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) President Obama signed into law in 2011 — giving the Food and Drug Administration new authority to regulate how food is grown, harvested and processed (i.e. produced) — places costly burdens on the small farmers who can least afford them.

What is the FSMA?

Prior to the law, the FDA’s approach to food contamination was reactionary. When instances of foodborne illnesses were reported, they responded, often with voluntary recalls. The new regulations, finalized last year and currently being implemented in phases, mark a distinct shift in an agency strategy that seeks to prevent contaminants from entering the food supply in the first place.

Food poisoning is a problem nationally. According to the CDC, of the 48 million Americans who get sick from eating tainted food every year, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die. Furthermore, massive recalls and settling the inevitable legal fallout costs the food industry billions. In addition to authorizing the FDA to issue mandatory recalls, the FSMA has incrementally unveiled 1,286 pages of new safety regulations.

While the food industry’s largest producers can afford to accommodate the various certifications, infrastructure changes and inspections that the law now mandates, small farmers already struggling to compete in their local markets risk getting priced — and regulated — out of business. Counter-intuitively, this is happening as consumer interest in food that hasn’t been doused in pesticides, wrapped in plastic and shipped halfway around the world should be offering regional farmers expanding economic opportunity in the form of community supported agriculture (CSAs) and weekend markets.

This consumer demand isn’t a mystery. Millions of Americans are in the process of learning that “not contaminated” and “healthy” mean very different things. It’s also become clear that what’s bad for our land and water is, inevitably, bad for us. The kicker seems to be coming up with federal policies that reflect these findings. On the food-and-consequences spectrum, the health affects of a sugar-filled, highly-processed (totally FDA compliant) diet are every bit as visible in the long-term as a listeria outbreak is in the short — obesity alone, for example, is reducing hundreds of thousands of lifespans while costing Americans an estimated $190.2 billion annually. That’s not meant to imply for one second that it’s the federal government’s job to ban Skittles® and hot dogs. No. But the enactment of mandatory policies that favor powerful special interests at the expense of people trying to make a more sustainable living should be equally unacceptable. (To better understand the federal government’s intricate role in what American farmers produce, clear your weekend schedule, hold all your calls, and jump into the Farm Bill.)

A closer look

LocalHarvest.org is an online directory that connects small farms to local customers. According to the website, the directory lists over 30,000 family farms, farmers markets, restaurants and grocery stores that feature local food, making “it easy to find good food.” In LocalHarvest’s most recent newsletter, under the headline Safe Food or Regressive Regulations?, Rebecca Thistlethwaite, a farmer and author from Watsonville Calif., suggests the new restrictions are not only potentially devastating to the local food movement, she doubts they’ll work:

“I can think of no other set of regulations that is going to discourage new farmers from getting started and existing farmers from scaling up than the FSMA rules. The results could be horrific for the advancement of a sustainable food system and do little if anything to reduce deleterious pathogens in our food supply.”

Thistlethwaite explains that, when fully implemented in 2018, the FSMA will require a farm to get each crop individually certified as food safety compliant. She says that under the act’s Produce Rule, only operations that gross less than $25,000 per year in fruit and vegetable sales will be categorically exempt from the new mandates. Depending on how many actions a farm must take to pass inspection, she estimates the cost of compliance could vary from $50 per acre to as much as $13,000 if larger infrastructure renovations are deemed necessary:

“These include costs such as water testing, testing compost materials, installing deer fencing, building an enclosed packing house, switching to all plastic harvest bins, renting port-a-potties with hand washing stations and the most time-consuming task of endless record-keeping. The record-keeping of organic certification will pale in comparison with food safety record-keeping. Things like daily temperature checks, recording when you pump, clean, and restock your bathrooms, recording when your employees wash their hands, how many deer footprints you found in a particular field, lot numbers for every box of produce you harvest, etc.”

As is too often the case, people find themselves enduring the particulars of a complicated law that, inadvertently or otherwise, favors corporate interests while disadvantaging small-scale businesses and the people who count on them. Echoing this sentiment, the newsletter features an excerpt from a letter written by LocalHarvest staff member (and farmer), John Gethoefer to Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D) his congressman in Oregon’s 3rd district. Adding his voice to the national chorus, Gethoefer articulates the frustration he and many farmers are feeling:

“We see first hand every day how difficult the practice of small, local family farming has become in America. It is a commonly felt view among the many farmers that we advocate for that federal agricultural policy usually does more harm than good for small, family farms. In turn, there is growing skepticism among these farming families that any legislation introduced will likely do more harm than good for their livelihoods and viability.”

This “growing skepticism” transcends agriculture as much as it does party or administration. There exists, and has for quite some time, a pressing need for the federal government to reacquaint itself with what the majority of Americans can and can’t afford. New regulations, no matter how good they look on paper, must consider the full cost of their implementation.

Gethoefer continues:

One example that we have seen recently in the struggle to promote local food systems is that large, institutional buyers of agricultural goods typically require vendors and producers to follow the USDA GAP (Good Agriculture Practices) or GHP (Good Handling Practices) standards. We have worked directly with both institutional buyers and farmers local to them and while we have tried to develop training programs that are cost-effective for the farmers, more often than not, the program is too costly for these farmers to adopt. As a result, very few local farming operations qualify to sell agricultural goods to these institutional buyers. While the intentions of GAP/GHP program are to increase safety for the general public, there exists many challenges in terms of equity and ultimately sustainability for the small, family farmers to adopt and therefore compete in the local marketplace.”

Making sure our food supply doesn’t get more poisonous (or unhealthier than it already is) is important work, but so is making every effort to increase the availability of minimally-processed, locally-grown food. If this law does the opposite, while simultaneously making it more difficult for small farmers to make a living, it ought to be thoroughly reworked. Or, as Thistlethwaite puts it:

“We need to insist that smaller farmers are exempt from these expensive one-size-fits-all regulations and give them a longer window of time to comply. There should also be whole farm/multi-crop audits that are done in one visit and that certified organic farmers don’t have to pay twice for essentially a similar inspection.”

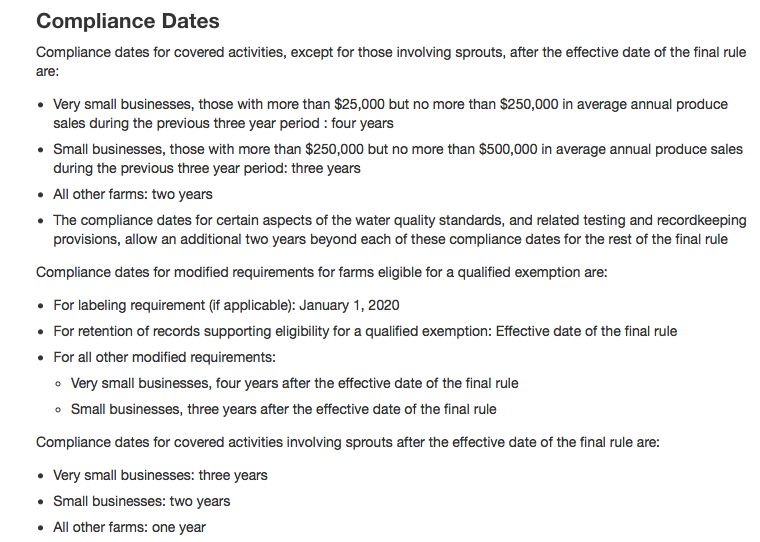

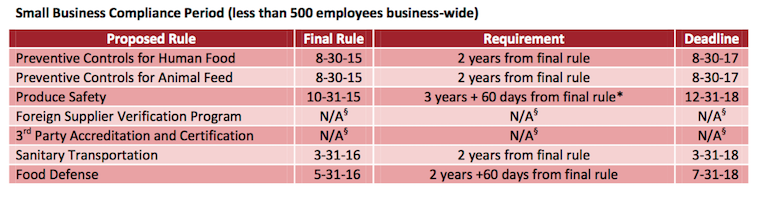

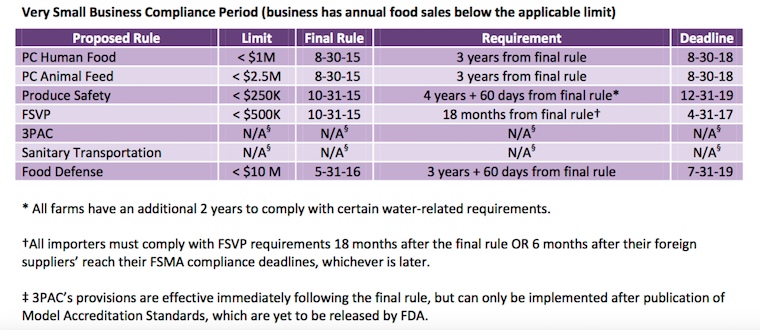

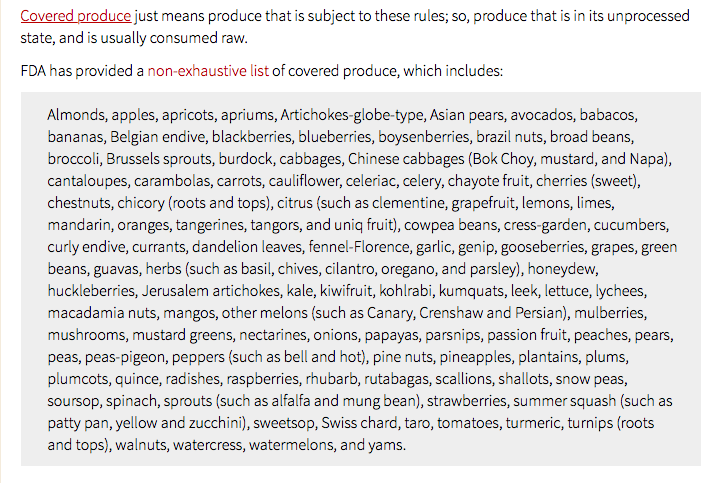

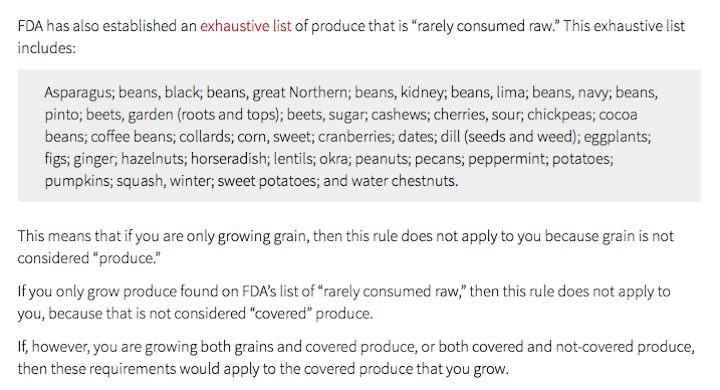

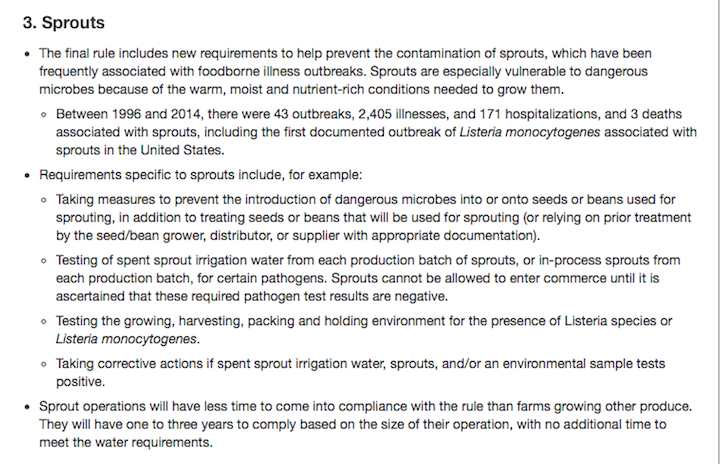

Editor’s Note 4/1/16: The following has been added to clarify FSMA compliance dates and provide additional information reguarding which fruits and vegetables are covered under the Produce Safety rule, finalized on November 13, 2015:

(Source: www.fda.gov Food Guidance Regulation)

(Source: Grocery Manufacture’s Association Reference Sheet for Compliance)

(Source: Understanding FDA’s New Rule for Produce Farms — Part I, National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition)

(Source: www.fda.gov Food Guidance Regulation)