Chemical compounds that incapacitate or kill, like phosgene, chlorine and sulfur mustard, were put into German artillery shells and delivered by howitzers on the frontlines in World War I. The diameter of the shells was 5.9 inches, prompting British soldiers to call them “five-nines.” By the end of the war, both sides were lobbing them. Whether or not a five-nine loaded with a chemical weapon landed in your trench had nothing to do with luck or lifestyle. War created the conditions for the exposure to the chemicals.

By the end of World War II, chemical manufacturers like DuPont, Shell and Monsanto shifted their military production to the domestic “war on pests.” At the Rocky Mountain Arsenal outside of Denver, the U.S. Army’s Chemical Corps made chemical weapons alongside private chemical companies like Shell Oil Company, which leased Army facilities at RMA to make pesticides.

Today the U.S. chemical manufacturing industry is an $800 billion business that has registered over 80,000 chemicals for use in the United States, with 2,000 new ones introduced each year. You and I are repositories for these chemicals. Toss your cigarettes in the trash bin, but you’re still breathing benzene from vehicle exhaust and industrial emissions. The Centers for Disease Control’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, issued in 2009 with updated data in 2017, looked for 308 synthetic chemicals in the blood or urine of Americans. Most were widely detected.

Some, like perchlorate, which can cause endocrine system and reproductive problems and is considered by the EPA to be a “likely human carcinogen,” was found in the urine of everyone tested. With unavoidable exposures to toxicants at every stage of life, stopping the systemic poisoning of our food, water, air, and soil is fundamental to giving individuals a decent chance to optimize their own health.

In 2017, more than 1.6 million people will be diagnosed with cancer in the United States. A small percentage of these cancers can be attributed to genetic troubles, whereas the remaining 90-to-95 percent of cancers are from influences outside the body that change what happens inside — some of which you can control and some you cannot. Those that we are told we can control, such as cigarette smoking, diet, alcohol, sun exposure, stress, obesity, and physical inactivity, are labeled “lifestyle factors,” or lifestyle for short.

An individual through their actions can help manage cancer’s progress or lower the risk of getting cancer in the first place; assuming one has the time, money, education and job options that allow one to make choices and know what choices to make.

Yet an emphasis on lifestyle always seems to come at the expense of meaningful public policy discussions. It diverts public attention from the collective problem solving and societal decision-making processes about how chemicals can, and under what conditions, cause harm, and what to do about it.

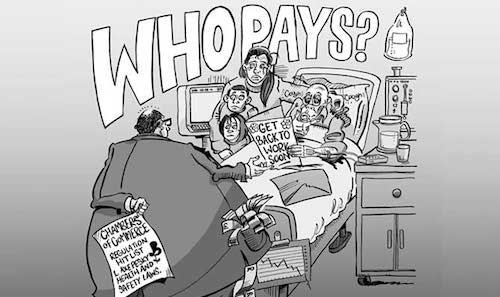

(Illustration: Hazards Magazine)

A 2015 California study that consisted of a 54-year follow-up of 20,754 pregnancies showed that women exposed in the womb to high levels of the pesticide DDT have a nearly fourfold increased risk of developing breast cancer. At its peak use in 1962, over 85,000 tons of the pesticide were used. A child in her mother’s womb exposed to the chemical had no choice in the matter. It is the responsibility of society, not the individual, to control cancer-causing chemicals.

So here we are, 100 years after World War I, and every American lacks protections from chemicals manufactured or used by U.S. corporations that degrade human health. Rory O’Neill, a professor of occupational and environmental health policy at the University of Stirling, Scotland, who is an editor of Hazards Magazine and the Work Cancer Hazards blog, tells us not to be fooled by the limelight on lifestyle for cancer risk. In the following post, slightly edited, he writes:

There are several problems with the emphasis on lifestyle, for a slew of chronic disorders, from cancer, to diabetes, to cardiovascular disease, to neurological disease, to…. Heck, all of them, and you can add in mental illness and suicide on top. This is not because the lifestyle effects are not real, but because:

It’s a smokescreen 1: Where research shows genuine concerns about occupational and environmental risks, the findings are questioned regardless of the strength of the evidence, and there is a cookie cutter response that says lifestyle is the real problem. This is driven by a berserkly well-resourced cancer industry selling this line, a process described well by Devra Davis, Janette Sherman, Joe LaDou and a noble succession of others

It’s a smokescreen 2: Where research questions a link, there is a chorus of let’s put this occupational and environmental red herring behind us, and there is a cookie cutter response that says lifestyle is the real problem. Witness what happened with the recent (and woeful) Oxford University paper dismissing the night work and breast cancer risk. This was widely and uncritically reported in the media. A BBC headline blared “Breast cancer risk ‘not increased’ by night shifts.” When positive findings are published, linking a chemical or workplace to cancer, this never happens — the lifestylists are waiting in the wings with their rebuttal every time. (For more information about night shifts and breast cancer, and a critical review of the Oxford University paper, see this story.

It’s your fault. When changing lifestyle is invoked as the key to prevention, the tone is generally one of blame — you have the wrong diet, you drink too much alcohol, you smoke, you don’t exercise. But these are consequences, not causes. Low wages, bad jobs, under-employment, unemployment, insecurity, and being born into and trapped in the lower socioeconomic strata are the problems that need addressing. These circumstances drive bad habits by removing positive choices. For example, you may have to “choose” processed, sugar-laden foods if your budget and your long hours in multiple minimum wage or less jobs may the alternative practically impossible.

Overloaded, stressed workers smoke and are more likely to demonstrate all the other bad habits. Put them on the night shift with no access to decent food and no prospect of decent sleep patterns and you soup up the effect. Add in prejudice based on gender or race, and you amplify these effects. Without looking at the socioeconomic drivers of peoples’ “choices,” blaming lifestyle just adds insult to injury.

Science is biased: Publicly funded independent occupational and environmental health science — by either academics or statutory agencies — is becoming rare. Research is increasingly (and frequently covertly) funded by industries motivated by concerns about the legal implications of medical research and not concerns about public health. Witness the 40-year wait for the new U.S. beryllium standard, which was introduced in March 2016; the respirable silica standard; the “science-fraud” and ongoing defense of chrysotile asbestos use (only just banned in Canada, and thanks to industry lobbying still legal in the United States); denial of low level benzene exposures causing cancers (thanks ACS — American Cancer Society); the links between Parkinsons and manganese; lack of regulation of endocrine disrupting chemicals; and the list goes on.

The tobacco industry’s playbook gets bounced from one industry to the next, with the highly remunerative process of seeding doubt enough to perpetuate another generation of exposures and another decade or two of profits.

The issue is not whether or not we own up to the real role that lifestyle factors play in causing cancer. It is that we understand how the lifestyle excuse is used to diminish or deny the role played by industry, by social prejudice and by economic disadvantage in perpetuating the circumstances that lead to many cancers and that influence cancer survival rates. Yet when we raise these issues we are shouted down and we are financially out-gunned by the same corporate interests that benefit from the cancer status quo.

“It’s your choice, red tape or bloody bandages.” — Rory O’Neill, editor of Hazard Magazine, talks complacent government, health and safety, labor and exploitation at a conference in 2013. (Video: Phillip Lewis / YouTube)