Native Youth “Paddle to Protect” Minnesota’s Water from Another Enbridge Pipeline

John Collins

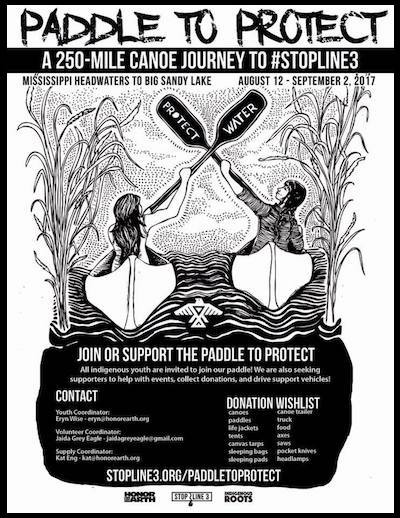

On August 12, a group of six indigenous teenagers and four adults from different tribes in Canada and the United States met at the headwaters of the Mississippi River, in northern Minnesota’s Itasca State Park, and set out on a 250-mile canoe trip to protest Enbridge Inc.’s latest endeavor — a so-called “replacement” of its aging Line 3 pipeline. The goal was to raise awareness about the danger the project poses to water quality, sacred wild rice beds and First Nation tribal sovereignty.

Enbridge — a multinational energy transportation company that operates the longest network of oil and liquid hydrocarbon pipelines in North America — is headquartered in Calgary, Alberta. It specializes in moving diluted bitumen, a heavy crude oil from the Athabasca tar sands, to oil refineries in the United States.

With unfortunate frequency, however, sections of the company’s sprawling 50,000 miles of pipe rupture, burst or otherwise leak their contents into some of the continent’s most ecologically sensitive areas. In 2010, for example, a 40-foot portion of Enbridge’s 6B pipeline broke near Marshall, Mich., sending more than one million gallons of the planet’s dirtiest fuel gushing into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River — the so-called “Dilbit Disaster” remains one of the largest inland spills in U.S. history, but it’s far from an isolated incident.

Enbridge’s existing Line 3 — 1,097 miles of 34-inch pipe that travels from Edmonton, Alberta, southeast through Saskatchewan and Manitoba before crossing a corner of North Dakota and 300 miles of northern Minnesota and ending at a terminal in Superior, Wis. — was originally constructed in 1967. The company’s new effort involves phasing that old line out, leaving it in the ground and building an entirely new version (this time with 36-inch pipe). Where the oil ultimately ends up and how it gets there — whether by truck, ship, train or another pipeline — is also the subject of controversy.

On September 2, three weeks and 250 miles from where the “Paddle to Protect” demonstration began, a crowd of family and friends gathered on a warm Saturday afternoon at the Big Sandy Lake recreation area in Aitkin County, Minn., to welcome the kids as they finished the last leg of their journey.

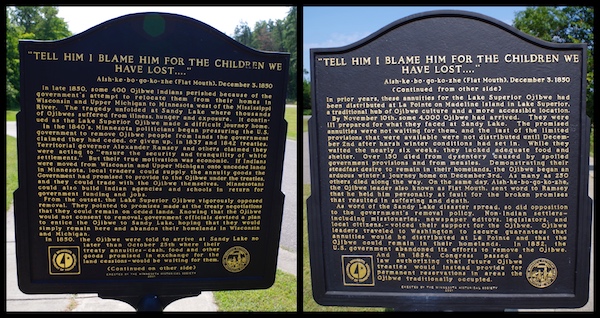

Not coincidentally, it was here, in the winter of 1850, that 400 Ojibwe perished under horrific circumstances after the federal government failed to make good on its promise to deliver much-needed supplies and provisions. A removal order signed by President Taylor had sent 4,000 Lake Superior Ojibwe to the remote lake, instead of the more accessible town of La Pointe on Madeline Island, to collect annuity payments that were not there.

A two-sided sign overlooking Big Sandy Lake recounts the tragedy that occured in 1850 when the federal government left hundreds of displaced Ojibwe to die. For an in-depth story on this history from a Native perspective, see Winona LaDuke’s 2015 article: Restoring a Multi-Cultural Society in a Sacred Place. (Image: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

Amid a series of speeches, dancing and feast preparations, Rural America In These Times spoke with some of the paddlers and those who showed up to support them.

Rose Whipple, a high school sophomore of the Isanti Dakota and Ho-Chunk Nations, lives in St. Paul. She explains why she decided to go on the journey:

“When this land gets poisoned, it hurts our people and it hurts our culture. And this pipeline is going through the homelands of many indigenous people — through treaty territories in Canada, Minnesota and Wisconsin.” She says, “It’s affecting people that don’t have much, poor communities that can’t fight back, but we’re trying our hardest.”

Rose Whipple and fellow paddler Cherokee Senevisai, 17, reunite with family and friends at Big Sandy Lake. (Image: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

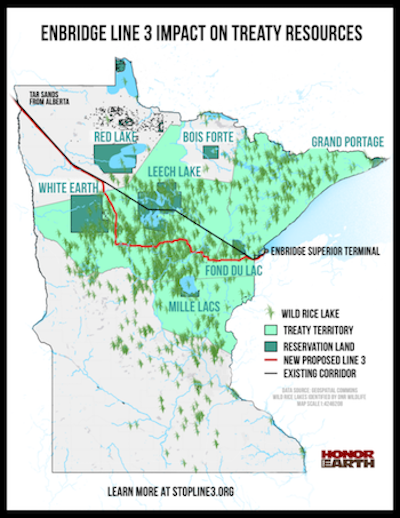

Though the company insists the project is a “replacement” of the old line, opponents say that’s disingenuous. It is, after all, 1,310 miles of brand new pipe that would carry far more oil than its predecessor while establishing an entirely new path through a different part of northern Minnesota. At a cost of $6.5 billion, a finished Line 3 would be the largest infrastructure project in Enbridge’s history. According to Honor the Earth, a Minnesota-based indigenous rights group (and long-time thorn in Enbridge’s side), “That’s not a ‘replacement,’ that’s a new line.”

(Source: Honor the Earth / StopLine3.org)

In an online fact sheet intended to set the record straight, the organization, which also sponsored the paddlers, explains it this way:

That line is old and crumbling, but instead of removing it, they want simply to abandon it and build a new one in a brand new corridor. The proposed new route endangers the Great Lakes, home to one fifth of the world’s fresh water, and some of the most delicate soils, aquifers and pristine lakes in northern Minnesota. It also threatens critical resources on Ojibwe treaty lands, where tribal members retain the rights to hunt, fish, gather, hold ceremony and travel. It is our responsibility as water protectors to prevent this. Tribal governments, environmental organizations and community members are uniting to stop Line 3. We expect a protracted legal and regulatory battle in the coming years.

A flyer released earlier this summer announces the Paddle to Protect trip. (Image: Honor the Earth / StopLine3.org)

In preparation for the canoe trip, Whipple says she and the others practiced on the water a little bit before leaving, but mostly learned as they went. “Now,” she says, “we’re like pros.”

Asked what stood out most about her time on the river, the city-based girl replies: “My whole life, I haven’t really been camping or anything like that. But being on the land and getting to wake up with the trees and getting to hear the water rush by, and all the animals at night that I’d never heard before or seen, and seeing all the eagles fly over us — there were so many eagles, they’re very sacred to us — it was amazing.”

Whipple is one of 13 young people known as “Youth Climate Intervenors” whom the state of Minnesota, this past June, acknowledged as a formal intervening party in the state’s Line 3 regulatory process. As a result, she and the other intervenors are in direct contact with the Minnesota Public Utility Commission (PUC) — the state agency ultimately in charge of reviewing Enbridge’s permit application and deciding whether or not to approve or deny the company’s plan. Enbridge is confident they’ll get what they want (because they usually do), but the intervenors are working to make certain their concerns about Line 3 are heard by the people in charge.

Though the state of Minnesota has yet to OK the new line’s proposed route (much of which runs near the reservations of two Ojibwe bands, the Leech Lake and the Fond du Lac) construction in Canada and Wisconsin is already underway. Consequently, small protest camps have started forming near the Minnesota-Wisconsin border.

On August 28, four days before the celebration and ceremony at Big Sandy Lake, the Douglas County sheriff arrested six water protectors who were demonstrating at the construction site. Work was temporarily halted after Alexander Good-Cane-Milk of the Yankton Sioux Tribe in South Dakota chained himself to a piece of heavy equipment. He and five others were taken to jail, including his girlfriend, Ta’Sina Sapa Win, who he met while protesting the Dakota Access pipeline near Standing Rock. She told Minnesota Public Radio, “Why did I want to come to Minnesota? Because our Ojibwe relatives helped stand for our fight against Dakota Access pipeline, and I’m going to stand with them in their fight.”

Valyncia Sparvier, 13, travelled from her home on the White Bear First Nation reserve in Saskatchewan to participate in the Paddle to Protect protest. Though she didn’t know it at the time, her mother, Brandy-Lee Maxie, who has spent the months since Standing Rock travelling and speaking to communities and schools around the country about pipelines, was one of the six arrested in Wisconsin.

Valyncia Sparvier, 13, from the White Bear First Nation in Saskatchewan at the Paddle to Protect ceremony. (Image: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

I asked her what it’s like to be a kid canoeing down the Mississippi River and finding out your mom had been arrested. “I didn’t hear from her for a day,” says Sparvier, “so then I started to get worried. Then we heard that six people were arrested and I messaged my mom over and over. Eventually she responded and explained that she had been arrested wrongfully. I guess the police were there to arrest the one person who did lock himself down on the equipment, but they ended up arresting more than that one guy.”

Sparvier says she was shocked. “I didn’t want this to turn out like Standing Rock — with all the cops responding to non-violence with violence. But I guess it might have to go like that. We’re just really sick of all these pipelines and people ruining water.”

On its way from Alberta into Saskatchewan, Line 3 crosses Sparvier’s reserve and many others, including the Carry the Kettle (CTK) Nakoda Nation reserve in Saskatchewan, on which numerous members of her extended family live. “The water near CTK is already pretty ruined,” says Sparvier. Asked how her mom was doing in the days following her arrest, she points to a woman sitting on a nearby hill and says, “She’s right over there.”

Brandy-Lee Maxie, Valyncia Sparvier’s mother, was one of six people arrested for protesting Line 3 in Wisconsin on August 28. (Image: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

I asked Maxie about her arrest, then quickly wished I’d phrased the question differently. “First of all, in my eyes, I was kidnapped,” she says, “because there was no reason to arrest me. I stayed law abiding on camera. And the entire time I kept asking if I was in the right and they said, ‘Yes you have a legal right to protest along this easement on the road.’ But when it happened it was almost as if they were targeting certain people. We were told to leave and were in the process of leaving when all of it happened.”

Maxie, 34, says she began reaching out to friends and family while trying to make sure the Sheriff understood that she was not only visiting from Canada, but that her child was here too, resisting in ways that were far away from the pipeline. “I’d tried my best to be law abiding, so I was kind of devastated,” says Maxie. “It was a very stressful situation because they put up a brick wall between me and my child. I had no way to let her know what was going on.”

Eventually, Maxie was able to contact her sister and mom who, at her request, asked the Paddle to Protect group not to tell Valyncia she’d been arrested until after she got out — it was something she wanted to do herself. “That was my biggest concern,” Maxie says, “How terrified the girls would be, because I’m Valyncia’s mom and another one of the paddler’s auntie, and they’re quite far from home. It would have been a lot more scary if they’d found out right away. But everything happened the way it did for a reason I guess.” She adds, “I saw a lot of wrong-doing and all of it was very well documented.”

With a court date set for late-October, Maxie made it clear that she did not want her experience to discourage the kids at Sandy Lake from resisting the pipeline. “This is a beautiful journey they’ve made. I’m so proud of everything that they’ve done here. I wanted to be here to encourage them not to be discouraged in their resistance because of what happened to me,” she says, looking around at the group of young paddlers celebrating. “But like we learned at Standing Rock, things like this are going to happen.”

Come to think of it, what did we learn at Standing Rock? Was it that when enough people believe in something, things change for the better? Or was it that when a multinational energy corporation feels threatened enough, it can summon a state’s governor to unleash the full might of a militarized police? The answer, I suppose, depends on how closely an individual was paying attention. But for the average urbanite, especially one on the receiving end of an energy company’s reliable stock dividend, the occasional oil spill probably isn’t too hard to write-off as the cost of doing business in a fossil fuel economy. That said, for many rural residents and indigenous communities on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border, the threats that new and existing pipelines pose to the Great Lakes, regional farmland and individual property rights — not to mention a warming planet — are not worth the risk. Through that lens, like we saw at Standing Rock, pipelines are a threat worth fighting against.

Prior to the official start of the welcome home ceremony, Winona LaDuke, founding director of the White Earth Recovery Project, cofounder of Honor the Earth and no stranger to fighting Enbridge pipelines, delivered the following message:

Thank you for your long journey for us — for going to places that many of us have not gone for a long time. That is one of the things about this battle with this black snake. We’ve gone to new places. We’ve left our territories. We’ve left our boxes, our communities, our cities and we’ve gone back out to our land. We’ve prayed, we’ve paddled, we’ve walked and we’ve ridden our horses through this territory to remind those spirits that we are here — have those spirits know that we are present. This is a very hard battle ahead of us. We must have our courage, we must have all of our strength. We must summon ourselves and all of our prayers at this time. That is what we must do, and this a good place for us to start.

Sept. 2, 2017 — the ceremony begins at Big Sandy Lake. (Image: John Collins / Rural America In These Times)

Update 9/11/2017: Officials in Minnesota have just recommended the state’s utilities commission reject Enbridge’s Line 3 permit request. As The Hill reports: “The state’s Department of Commerce said Monday that Enbridge’s proposal to replace its Line 3 pipeline would not benefit the state and instead pose environmental risks. It will ask the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission to deny a permit for the project, a decision due next year.” To read the full story, click here.