Will Bernie Sanders’ Momentum Increase Support Among Voters of Color?

Sanders definitely has a problem with black voters. But the more they get to know him, the more supportive they become.

Waleed Shahid

Much ink has been spilled regarding Bernie Sanders’ poor showing with voters of color, particularly black voters. Suggested explanations have included his stance on reparations, his “class-first” or “single-issue” approach to addressing inequality, his poor handling of the Black Lives Matter protest at a Netroots Nation conference in July 2015 and his inability to make a compelling case that he could deliver on his promises as president.

The discussion up to this point has been driven by social media, pundits and a handful of progressive writers and thinkers who have been unable to accurately describe mass voter behavior. Most voters still aren’t paying close attention to the presidential election, and those who are tend to receive much of their information from television. Many are still relatively unfamiliar with Sanders’ campaign and candidacy (though they are relatively in favor of his social democratic policy platform).

While Sanders could be doing much more to connect the dots between his message on economic inequality, corporate influence on politics and structural racism, this is not the major driver of his poor performance among voters of color. The discussion surrounding race and the Democratic Primary would lead one to believe that Hillary Clinton polls well with voters of color because she is strong on issues regarding racism and racial inequality. This framing inaccurately suggests that voters simply prefer Clinton’s agenda over Sanders’ rather than voters tending to prefer candidates who they are familiar with.

This is a simpler and more compelling explanation for Bernie’s lack of popularity: voter behavior in the Democratic Primary is not simply about “the issues,” but about Sanders’ lack of name recognition and familiarity in communities of color. When one candidate has been highly visible in the public arena for over two decades while the other has rarely been seen (at least outside his home state), it impacts voters’ perceptions.

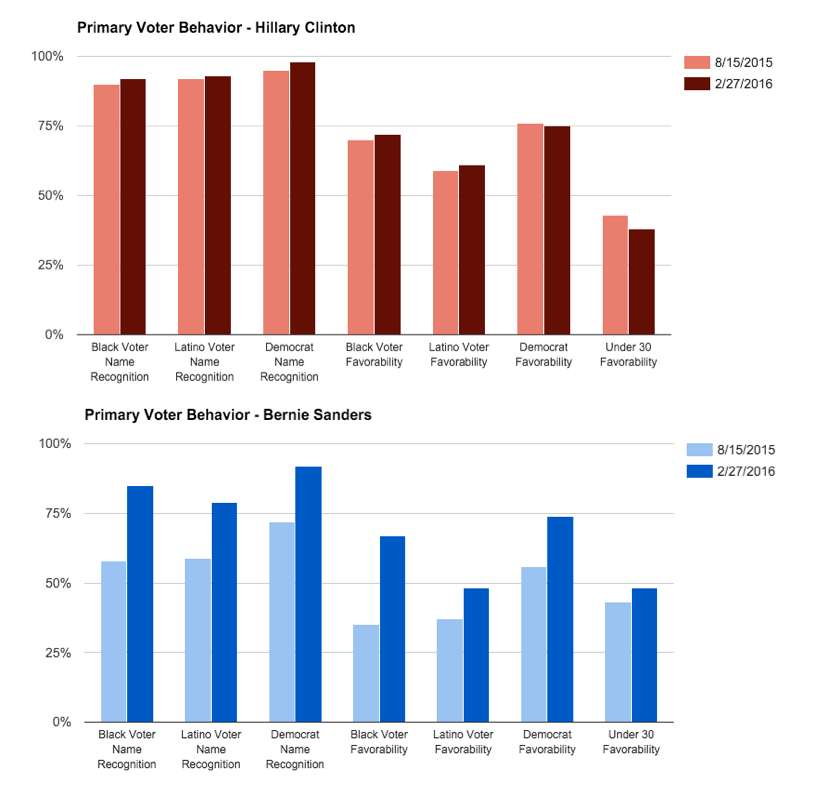

Recent polling by YouGov and The Economist shows that voters tend to prefer the candidate they are familiar with. In August, over 40% of black and Latino voters said they did not know Sanders, compared to 9% who did not know Clinton. Higher name recognition led to higher favorability ratings, with Clinton beating Sanders 70-35 and 59-37 on a favorability scale among black and Latino voters. (Of course, there are many other factors driving Sanders’ poor performance with voters of color: local political machines responsible for voter turnout, Sanders’ record on gun control and criticism of the highly-popular Obama presidency, increasing political polarization along racial lines, skepticism of Sanders ability to deliver, the Clinton family’s popularity with communities of color, southern Democrats tending to be more conservative, electoral risk-aversion among non-white voters and the historical attachment of communities of color to and confidence in the Democratic Party.)

Recognition seems to be slowly shifting in Sanders’ favor as his campaign racks up more victories. In the most recent poll, Sanders’ name recognition and favorability ratings have simultaneously increased among communities of color, particularly younger voters. Sanders tied Clinton among voters in Mississippi under age 30, where black voters make up 89% of the Democratic electorate. In Michigan, Sanders virtually tied Clinton with black voters under 40. (He also won 60% of the vote in Dearborn, Michigan, one of the largest Muslim and Arab-American communities in the country.) Still, Bernie has a lot of ground to make up among voters of color.

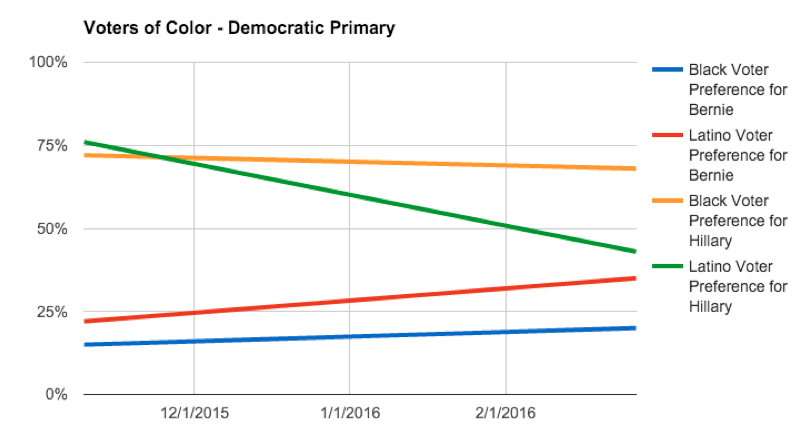

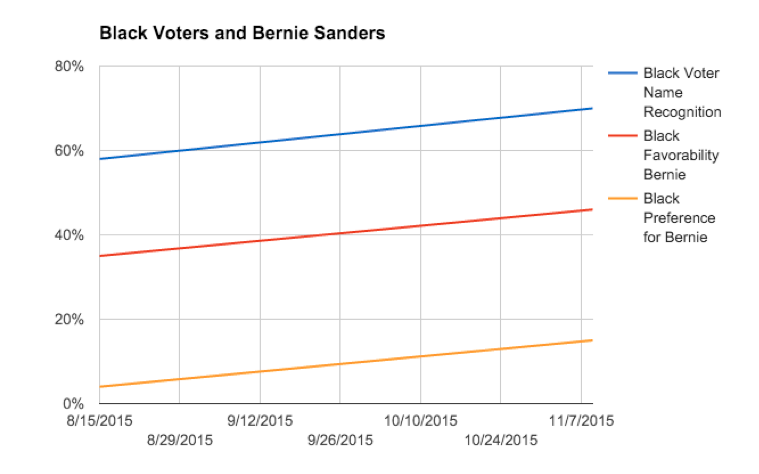

Baltimore Post-Examiner writer Carl Beijer recently compiled the same set of polls to show that Sanders began the race with almost no name recognition among black voters and that the more black voters get to know him, the more they like him. Electoral campaigns are grounded in getting large numbers of voters familiar with a candidate at the door and on television. While Sanders still has to make an introduction, Clinton began the race with a head start, receiving very high-levels of name recognition and favorability among voters of color. In the past few months, Sanders has gained considerable ground and, just as we saw in Michigan and Mississippi, has seen his favorability increase in communities of color as his name recognition rises. Clinton, meanwhile, has seen her numbers fall, particularly with Latino voters.

Television continues to be the primary source of information for voters. As Beijer points out, “the name recognition gap [between Clinton and Sanders] is almost entirely explained by national media coverage.” Sanders received only one-sixth of the broadcast news coverage in 2015 that Clinton did — 20 minutes of coverage to Clinton’s 121.

The huge influence of television coverage on electoral preference is most aptly displayed by the rise of Donald Trump, whose media savvy and attention-seeking tactics have almost single-handedly driven his poll numbers. Trump’s ground game is relatively non-existent compared to other candidates; his media presence, however, is approaching saturation.

Clinton’s strong attachment to the Democratic Party has likely helped her, especially since Sanders has never identified as a Democrat. The Democratic Party is not viewed with the same suspicion by black voters as by white progressives and white working class Democrats. African Americans are much less to describe themselves as independents compared to whites (26% vs. 40%).

The other elephant in the room is that many voters of color may not hold hope that the political system can be transformed in the way that the Sanders movement says it can. Why should voters trust that an unfamiliar Senator from Vermont can deliver on idealistic proposals like free healthcare and college, raising regulations and taxes on Wall Street or a $15 minimum wage when America’s first black President faced such uncompromising opposition from the GOP and the Tea Party on every single common sense proposal from healthcare to immigration reform to gun violence?

Voters of color have a lot at stake in elections, which can make them more prone to go with the safer candidate perceived to be tougher against Republicans. Only 11% percent of voters in South Carolina said they wanted a president from outside the political establishment. Clinton was supported by over 9 in 10 voters saying experience was the most important quality in choosing a candidate, and 8 in 10 of those said it was most important to choose a candidate who can win in November.

But Sanders has been singing a different tune for quite some time: that his campaign has never been about a single candidate or a single election. His campaign’s narrative has always been about creating a movement to transform our democracy and bring about a political revolution.

Sanders has performed poorly with voters of color overall, but a generational divide is also emerging between young and older voters of color. In Texas, Sanders won 59% of voters of color under 30, compared to just 12 percent of voters of color over 65. Sanders only lost black voters under 30 by a 43-56 margin in South Carolina, but Clinton won black voters over 30 in SC by a whopping 96 – 3 percent. Millennial voters of color have shown much more support for Sanders campaign and are much more likely to engage with the campaign’s large social media presence. But these voters tend to vote in much smaller numbers than their parents and grandparents. Voters under 30 made up only 15% of the electorate in both South Carolina and Mississippi, while voters over 45 made up over 60% of the electorate in both states

Anyone who has ever worked on an electoral campaign knows the deep impact of conversations at the door with ordinary voters. Doorknocking helps campaigns introduce the candidate and their platform to voters who often don’t have time to pay attention to every detail of the election. The first step is helping voters get familiar with the candidate. Since Sanders struggles with familiarity, it’s a steep climb to get voters from recognition to familiarity, from familiarity to a positive opinion, and from a positive opinion to preference over Clinton. But that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.

I spent a weekend knocking doors in a working-class African American neighborhood in South Carolina getting out the vote for Sanders. Our script involved asking people what they cared about and then pivoting to Sanders’ stance on their issue. Even a week before the election, most voters I talked to were unfamiliar with Sanders. One voter, a black woman, told me that she was voting for Hillary Clinton. I said that I was knocking doors for Bernie Sanders campaign for president and asked her what the biggest issue in her life was.

“I work a lot,” she said. “But I can’t survive on the minimum wage. And I care about healthcare because mine is about to expire.” I described the differences between Sanders and Clinton on minimum wage and healthcare: Sanders was for a $15 per hour minimum, Clinton was for $12. Sanders believed that health care should be a right for all people, that every American should be covered with no copays, no deductibles and no long arguments with insurance companies. And that we could afford it by raising taxes on the most wealthy people in our country.

She responded by saying she had recently gotten upset while watching a reality television show. “I watch these television shows with all these wealthy people. I don’t want to be rich, but some people have so much while the rest of us are just struggling to get by. I don’t think people who work full time should have this much trouble getting what they need to survive.”

I described to her that the Sanders campaign was really about a political revolution of millions of Americans coming together to stand up to Wall Street and the billionaire class in our country who too often keep people from having what they need. She nodded her head and smiled.

“That’s what we need,” she said. “ I think you changed my mind. But I have to go look into this more.”