The supply of land is fixed, so who owns it matters. Much has changed since the feudal days of medieval Europe, but if you want to own some acreage in the United States — the kind of swath an agribusiness corporation or mining company might also covet — your best bet is to marry into or inherit it. This reality is particularly problematic for the next generation of American farmers and, by extension, the future of our food system.

“The local regional food economy we want, needs territory,” says farmer, activist and grassroots organizer Severine von Tscharner Fleming. “Global demands and pressures have lengthened supply chains and concentrated control — water pumped from our aquifers irrigates low-value crops destined for distant markets. Cattle raised in family operations are sold at auction to be fattened on feedlots controlled by the beef monopolies.”

These larger structural issues are shaping our national landscape, says von Tscharner Fleming, and her latest startup, a collaborative effort called Agrarian Trust, aims to secure alternative land access arrangements for new farmers.

The Trust estimates that “in the next 20 years, 400 Million acres of U.S. farmland will change hands.” As today’s farmers age and retire, current social and economic trends suggest these acres will fall into the hands of an ever-consolidating few and that the land itself will endure further exploitation in the name of one short-sighted economic gain or another.

Land prices in the United States have skyrocketed in recent years, the Agrarian Trust website notes, “driven by an unregulated speculative market-place, international investment, a distorted subsidy system and by unrestrained development pressure.”

On the other hand, a surge in intergenerational support for a more sustainable approach to the environment, more resilient regional economies and local, organic CSAs (Community Supported Agriculture) offers hope that a fundamentally different strategy is already in progress. The problem is that while scores of young people across the country are committed to reshaping the agricultural and economic landscapes of rural America, the cost of actual land is prohibitive and the situation is only getting worse.

Partnering with like-minded allies in the new economy movement, such as the Oakland-based Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) and the Schumacher Center for New Economics, the Agrarian Trust is working to preserve access to affordable farmland, in perpetuity, for the purposes of ecologically responsible, community-owned food production.

The group’s three primary goals are to:

- Build the issue (what Henry George called “the Land Question”) and reframe the solution through public symposia, collaborative advocacy campaigns, and stakeholder meetings.

- Support the network of stakeholders and service providers through collection and documentation of innovative models for land access. Create a comprehensive resource portal to pool the useful tools already developed.

- Build the Agrarian Trust that can hold and transfer land to regional land organizations, and ensure its sustainable and productive stewardship for generations to come.

To whom does the soil belong?

A commons-based approach to land stewardship and agriculture is not a new concept. In 1881, Henry George — economist, social theorist and author of the best selling book on economics Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth: The Remedy—published the The Land Question.

Published in 1879, Progress and Poverty, by Henry George was translated into 10 languages and sold millions of copies. (Photo: archive.org)

Adding to a body of work that would eventually culminate in an economic philosophy known as Georgism (the belief that the economic value derived from land, including natural resources and natural opportunities, should belong equally to all residents of a community, but that people should individually own the value of what they themselves produce), George wrestled with two questions: “To whom rightfully does the soil belong?” and “Who are justly entitled to its use and to all the benefits that flow from its use?”

Clearly feeling the 19th century Bern, George wrote that, before the Land Question could be addressed, society first had to answer these fundamental questions:

- whether, their political equality conceded (for, where this has not already been, it soon will be), the masses of mankind are to remain mere hewers of wood and drawers of water for the benefit of a fortunate few?

- whether, having escaped from feudalism, modern society is to pass into an industrial organization more grinding and oppressive, more heartless and hopeless, than feudalism?

- whether, amid the abundance their labor creates, the producers of wealth are to be content in good times with the barest of livings and in bad times to suffer and to starve?

A symposium about land transition, continuity and commons

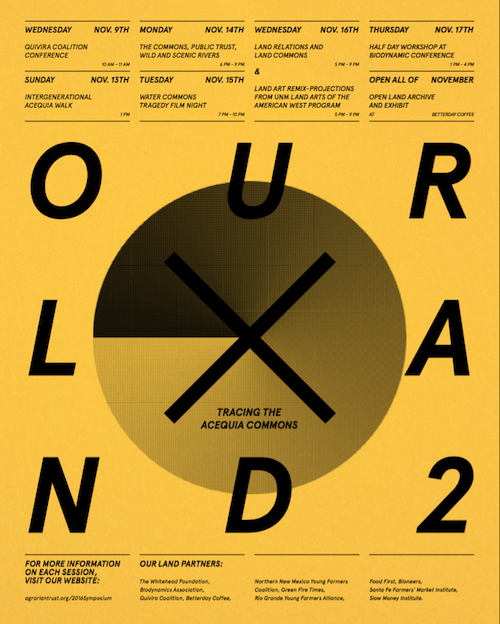

From November 9 through 17, in Albuquerque and Santa Fe, N.M., the Agrarian Trust will be hosting a symposium, “Our Land 2: Tracing the Acequia Commons.”.

Presented in partnership with a host of food and economic justice organizations — Quivira Coalition, Biodynamic Association, Santa Fe Farmers Market, Slow Money Institute, Bioneers, Betterday Coffee, Rio Grande/ Northern New Mexico Young Farmers Alliance and the Whitehead Foundation — the symposium will focus on land-use and governance regimes of the southwest and desert regions.

In the United States, Acequias (which refers to both shared irrigation ditches and the community network that manages them) are unique to New Mexico and southern Colorado. Brought by the Spanish, remnants of these systems can also be found in other areas of the Southwest. (Caption / Photo: Paula Garcia / bmccommons.org)

Our Land 1, which boasted over 600 attendees from 13 states, was held in Berkeley, Calif., in 2014. This time, Fleming says, in addition to studying the 400-year-old acequias upclose, the event will feature talks about water privitization and poisoning. Attendees will also learn about public trust law — a commonwealth legal framework with roots in ancient Rome that protects ecological systems. The Agrarian Trust press release reads:

In the next 20 years, 400 Million acres of U.S. farmland are predicted to change hands. The consequences of this inflection in ownership are wide-ranging — its impact will be felt by all of us.

Agrarian Trust has the mission to shift the destiny of farmland use in the United States, in terms of stewardship and access. We aim to push this system towards organic practices, community ownership models, and production for regional markets for more democratic and sovereign places and people. We present this symposium as a way to invite a broad audience into consideration of “the land question” and hope to provoke conversation and action.

The Southwest’s acequia systems are some of the longest settled agricultural lands in North America. Here, the constraints of desert ecosystems confined traditional indigenous and later Hispano-Spanish agriculture to the bottomlands, fed by low-tech ditch irrigation. The acequia systems represent a powerful and direct commons-based governance regime and a curriculum from which many other regions can learn. In considering future prospects for sustainable agriculture and self determined regional economies — it seems useful for a national audience to learn from the bounded and mature farm systems of the Southwest, to look across regional contexts at issues of the commons, farmland conservation and evolving legal notions of public trust.

Join us as we explore the overlapping and conflictual land-use patterns of the Southwest, and consider the prospects for our common resources and make plans for action. We welcome farmers of all ages, eaters, conservationists, planners, artists, anyone interested to relate, and to intervene in the destiny of the landscape that sustains us.

Can our regions shift towards food sovereignty? Can our agrarian systems become more harmonious with their wild habitat? Can we be guided by our traditional commons? Let us learn together from national and regional speakers, filmmakers, artists, archivists and geographers.

Ultimately, Agrarian Trust hopes that the history, management regimes and future prospects of acequia systems will serve as an inspiring model for other commons-based systems. The question is: Can these ditch commons be expanded to include their uplands and headwaters, or will ditch rights be lost to privatization and sold to developers?

“Increasingly, communities recognize that a regional farm economy is more responsive, adaptive, resilient and culturally satisfying,” says von Tscharner Fleming. “We want more diverse, more local, less thirsty, more prosperous regional food systems. It is in this context that we talk about land access for incoming farmers, about successful businesses, and about land transition for existing farms and retiring farmers, as well as mechanisms for restoration of degraded ecological features and infrastructures.”

To view the event’s full schedule, click here. (Image: agrariantrust.org)