“Populism” (according to the most readily accessible digital dictionary) means “support for the concerns of ordinary people” or, defined even more generally, “the quality of appealing to or being aimed at ordinary people.” Political populism, as we saw last year, has no allegiance to a specific ideology (or party). Donald Trump rode a populist wave into the White House, but Bernie Sanders spent two years generating an impressive swell of his own. In other words, populism is the vehicle with which a significant number of everyday people set out to teach the elites of an era a lesson — but it’s not the destination.

In “What Is A Populist?” published earlier this week in The Atlantic, Uri Friedman explains the phenomenon’s flexibility this way:

No definition of populism will fully describe all populists. That’s because populism is a “thin ideology” in that it “only speaks to a very small part of a political agenda,” according to Cas Mudde, a professor at the University of Georgia and the co-author of Populism: A Very Short Introduction. An ideology like fascism involves a holistic view of how politics, the economy, and society as a whole should be ordered. Populism doesn’t; it calls for kicking out the political establishment, but it doesn’t specify what should replace it. So it’s usually paired with “thicker” left- or right-wing ideologies like socialism or nationalism.

When studying populism, socialism, nationalism, fascism or any other ism for that matter, the United States is getting old enough to provide us with historical parallels — candidates, elections and social circumstances that can be mined for relevant national comparisons. In the fullness of time, some are more relevant than others. Last June, for example, before Donald Trump won the 2016 election and when many were speculating he wouldn’t, Forbes published “Before Donald Trump, There Was William Jennings Bryan” in which author Tim Reuter’s writes:

Imagine the following scenario. Years after the stock market has crashed, millions remain unemployed. Severe political polarization has paralyzed the federal government. As the country enters a presidential election year, populists sense their moment has arrived. They not only attack accepted economic doctrines, but one populist wins the presidential nomination of a major political party.

What year is it? It is 1896…

Unlike Donald Trump, William Jennings Bryan, a Democrat, ultimately lost that election — sending the party into an electoral tailspin that took nearly 40 years to correct — but Reuter’s comparison is still insightful as is his account of the rise and fall of populist movements in the United States. Of particular interest to Rural America In These Times, is Reuter’s analysis of presidential politics four years earlier, in 1892 — a time when, in his words, “The first rumblings of the populist insurgency that would reshape American politics went largely unnoticed.”

He writes:

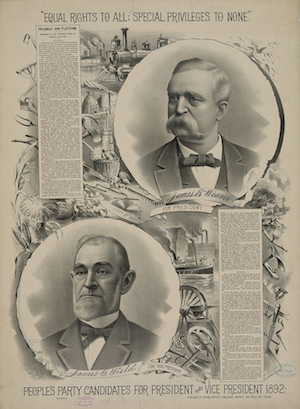

In the summer of 1892, farmers and labor activists met in Omaha, Neb., for a political convention. On July 4, the People’s Party issued its platform. It denounced the division of society into “two great classes — tramps and millionaires.” The list of proposed remedies included government control of the railroads, a “graduated income tax,” and a “national currency” that was “safe, sound, and flexible.” The convention nominated James B. Weaver, a former congressman and presidential candidate for the short-lived Greenback Party. On Election Day, Weaver won twenty-two electoral votes and 8.5 percent of the popular vote.

Though I’d not seen the above story at the time, I posted a similarly themed and titled article last November, “Before Bernie Sanders: A 19th Century Populist’s Run for the Presidency,” in which I noted the striking similarities between the economic rhetoric (and subsequent popular support) of Weaver and Bernie Sanders (who was in the process of giving Hillary Clinton a run for her money).

In short, Weaver and the People’s Party (known as the Populists, from which the word “populism” derives) were the product of a grassroots farmers movement that began decades earlier, in the wake of the Civil War. In the South, the crop-lein system had farmers trapped in a perpetual cycle of poverty and never-ending debt. Meanwhile in the North farmers found themselves at the mercy of excessive price fixing, hostile bankers and a monopolistic railroad. Something had to give. Twenty-seven years after the war, Weaver published (as politicians with presidential aspirations often do) a political manifesto—A Call to Action—in which he excoriates the increasing role that wealthy elites and the corporations of his time were playing in politics.

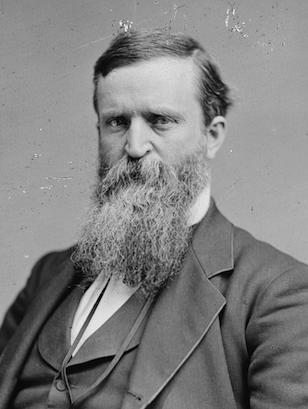

James B. Weaver, the People’s Party candidate for president in 1892, was was born in Ohio in 1833 and raised in Iowa. (Images: britannica.com)

The language is often times intense. In fact, it makes most contemporary fat-cat-trash-talk sound tame. Keep in mind this was published 125 years ago in a time of massive income and social inequality, technological change, simmering racial tensions and during a presidential election. Here’s an excerpt:

The slave holding aristocracy, restricted both as to locality and influence, was destroyed by the war only to be succeeded by an infinitely more dangerous and powerful aristocracy of wealth, which now pervades every State and aspires to universal dominion. Its first conquest was the subjugation of the dominant political party of the nation, while it required the other to keep the peace, under the threat that if it did not succumb it should never come into power.

Next it secured control of State politics, and finally found expression in a vast network of corporations which have seized upon almost every field of labor and every department of human effort. Neither the military achievements of Caesar, the exploits of Cyrus, Hannibal, Alexander, nor the dazzling conquests of Napoleon in the fields of war, can compare with the stupendous victories of organized capital in this country during the past 25 years. They have outstripped the imagination, rendered fiction dull and uninteresting, and robbed romance of its charms. The chief spirits through whose agency all these things have been accomplished are not unmindful that they are in conflict with both private right and the public welfare.

They, above all others, know the extent of their wrong doing, and they fear reprisals at the hands of the people. To prevent remedial legislation they have filled the Senate of the United States with men who represent the corporations and the various phases of organized greed. The ideal Senate, longed for by Mr. Dickinson [one of the wealthiest founding fathers and 5th president of Pennsylvania who died in 1808] — a Senate composed of men of wealth and resembling the British House of Lords — has been realized and has long been in full operation. The method of selection was found to be peculiarly well fitted to their scheme. There is one characteristic common to all wrong doers — they work in the dark and conceal their motives. You know nothing of their purpose until the stab is inflicted. Like the cat, they walk in quest of prey with velvet feet; and like the assassin, they lie in wait and spring upon you without warning.

The corporations never make public their purpose. They hold no public meetings. Their plans are laid in the counting room, around the lunch table, and in the secret meetings of their directors away from the public. When the plan is matured, a skillful agent is employed to carry it out, and a check is drawn to cover expenses. The people at large are about their daily toil in the field and the workshop. They are honest, unsuspecting, patriotic, and devoted to their respective parties. The work that is to rob and ruin them is being done under cover.

The corporations — apparently wholly indifferent — having determined whom they wish to elect to the United States Senate, the next thing in order is to secure the nomination of suitable Legislative candidates — men who can be trusted to do their bidding. Secure in this, no effort or expense is spared to insure a triumph at the polls. Usually the name of the man whom they intend to elect to the Senate is kept in the background. The canvass is made wholly with reference to other issues. But as soon as the election is over, a venal subsidized press which has been party to the concealment during the campaign, suddenly throws off the mask and discovers that the senatorial question is all important and you then hear of nothing else.

They suddenly discover that Mr. A or B is just the right man for the position, and the one above all others whom the party and the State should delight to honor. At the proper time headquarters are opened at the State Capital, and a lavish expenditure of money begins, while the people look on with amazement and wonder where the money comes from. The local manipulators, many of whom were parties to the conspiracy from the beginning, are sent for and kept upon the ground as a guaranty that the various bargains made throughout the State, shall be carried out. Then comes the party caucus, which all must attend and to whose decrees all must submit or lose their party standing. Finally the majority of the caucus, which is usually a minority of the Legislature, nominates the corporation candidate and the drunken brawl that has rendered the State Capital disorderly for a fortnight or more, is at an end and the people are betrayed.

Weaver, of course, lost. But the accusations he leveled at the 1892 status quo (including the revelation that corporate interests were purchasing Senators) resonated with enough Americans at the time to earn him 22 electoral votes, the most any third party candidate had received since the Civil War. Many of the social policies he proposed, furthermore, did not go away. Indeed, sometimes populists win even when they lose by making it impossible for the powers that be to continue ignoring the people and issues the movement mobilized in its prime. If Donald Trump’s record shattering stock market, for example, ultimately fails to turn into jobs that pay more Americans a livable wage, it’s likely Bernie Sanders’ core economic message — that government should work for the people not Wall Street, and that no one working full-time should be living in poverty — will be echoed again, all the more loudly, in four years.

As Uri Friedman’s piece in The Atlantic does a thorough job of explaining, precisely because populism is an ideological chameleon — often supplemented with whatever authoritarian, nationalist or socialist inclinations held by those leading the particular movement — populist victories can (and often do) manifest in all manner of terrible ways around the world. Other times, they change the political realm for the better.

Once populism’s power has been successfully harnessed, progress for “the people” depends on how that group is defined and the trustworthiness of the populist leading the charge.