It’s Not Just Oregon: A Closer Look at the Sagebrush Insurgency

Rural America In These Times

High Country News (HCN) has just released a 4-story special report on the escalation of the opposition to federal land management out West — the Sagebrush insurgency. It’s recommended reading for anybody interested in learning more about how the modern anti-federalist movement is both similar and different to those that came before it. Rogue sheriffs, social networking and bigger guns are now variables in our increasingly frequent, potentially deadly disputes over public land. Gretchen King, HCN’s outreach coordinator, explains, “These stories focus on the hidden connections between the economic downturn, anti-government sentiment, and a sprawling network of organizations, actors and movements.”

Last year, in economically struggling Josephine County, Ore., the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) told two entrepreneurial miners searching for gold under the General Mining Law of 1872 to cease their operation until additional paperwork could be filed. The miners viewed this request to stop as an infringement of their constitutional rights and turned to the Oath Keepers — a national alliance of self-described patriots committed to preventing overreach of the federal government — for assistance. The group pledged their support and launched “Operation Gold Rush.” Showdown at Sugar Pine Mine, by Tay Wiles, explores how the Oath Keepers, prior to their presence at the occupation of Malheur Wildlife Refuge, transformed this local mining dispute in rural Oregon into “a major insurgency event.”

Whether it’s the Bundy Ranch standoff, Operation Gold Rush, or the Malheur occupation, today’s Sagebrush Insurgencies are “radicalization nodes,” as Daryl Johnson, a domestic terrorism expert and former Department of Homeland Security employee, describes them. At each new gathering, far-flung Patriots forge new relationships, and new recruits are drawn into the movement. At a meeting of ranchers in Utah last fall, the head of Arizona’s branch of the White Mountain Militia, Cope Reynolds, encouraged ranchers to refuse to pay their grazing fees and offered his group’s services to ward off federal overreach.

Armed militiamen stand guard at the Sugar Pine Mine in Josephine County, Oregon, last April as part of what Josephine County Oath Keepers called Operation Gold Rush. The Oath Keepers’ goal was to defend the constitutional rights of miners George Backes and Rick Barclay who had been ordered to file new paperwork or stop mining their claim on BLM land. (Photo/Caption: Jim Urquhart/Reuters)

The second iteration unfolded in the mid-1990s, provoked by former President Bill Clinton’s conservationist approach to federal land. While that rebellion became violent and coincided with a nationwide surge in anti-federal extremism, the land-use folks rarely crossed paths with the so-called “Patriot” groups. Today, though, the barriers are down. Now, a single event like Recapture, the 2014 Bundy Ranch standoff or the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation, broadcast globally and instantly via social media, draws supporters from across the extreme right, from other Sagebrush Rebels to pro-gun militiamen to local politicians who have no qualms about standing cheek-by-jowl with people aiming rifles at federal agents.

These county sheriffs, sympathetic to anti-government efforts, are subsequently empowering and emboldening those who believe that drastic action and the threat of violence are both necessary and within their legal rights. Richard Mack, the former Arizona sheriff who sued the federal government in 1994, is referenced in the excerpt below.

By refusing to enforce federal and state laws that they deem unconstitutional, whether they involve BLM road closures, gun control, drug laws or bans against selling unpasteurized milk, Mack says sheriffs can lead the fight to rescue America from the “cesspool of corruption” that Washington, D.C., has become. If need be, he says, sheriffs even have the power to prevent federal and state agents from enforcing those laws, thereby nullifying federal authority. If a particular sheriff doesn’t rally to the cause, then the voters should kick him out of office. And Mack and his organization have been quietly fielding opposition candidates in many counties. In fact, he is one of the forces behind the Constitutional County Project, which aims, this year, to elect a whole slate of “constitutional” candidates to office in Navajo County, Arizona, in what amounts to a nonviolent coup d’état. “There is no solution in Washington, D.C.,” Mack told me. “If we’re going to take America back it’s going to be at the local level.

Colorado sheriffs flank Weld County, Colorado, Sheriff John Cooke in 2013 as he announces that 54 Colorado sheriffs had filed a federal lawsuit challenging two gun control bills passed by the Colorado Legislature. (Photo/Caption: Brennan Linsley/AP)

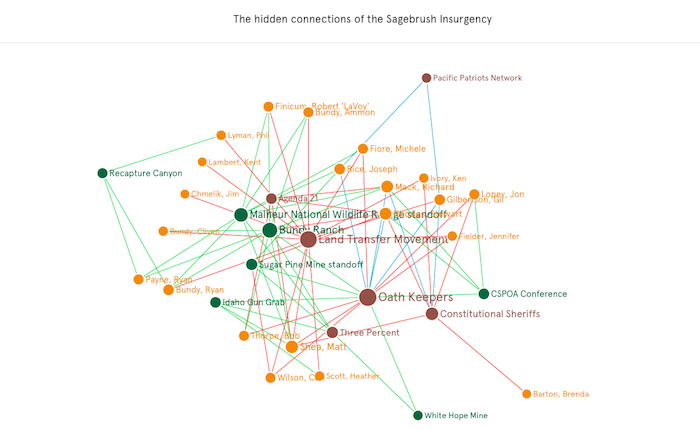

But recent events also suggest that these like-minded networks are growing to include people not directly impacted by western land management issues. In other words, this isn’t just upset miners and frustrated cattle ranchers. The Hidden Connections of the Sagebrush Insurgency, by Jonathan Thompson and Brooke Warren, explains how once scattered and ideologically distinct brands of anti-federalist sentiment are now uniting around their common beliefs.

Whereas the Sagebrush Rebellion of old was driven largely by pragmatic, grassroots concerns, today’s version is purely ideological — a nationwide confluence of right-wing and libertarian extremists. Many of them have little interest in grazing allotments, mining laws or the Wilderness Act. It’s what these things symbolize that matters: A tyrannical federal government activists can denounce, defy and perhaps even engage in battle with. This movement, which has grown increasingly virulent since President Barack Obama’s election, has created a stew of ideologically similar groups, ready to coalesce around each other when necessary.

Thompson and Warren further warn that the new found level of organization these radical groups employ could eventually spill-over into the political process.

As we head into an election year, it’s worth noting that many of the extreme actions carried out by fringe groups, such as the Malheur occupation, inspire other hard-core ideologues and ultimately translate into votes for like-minded politicians. In return, those politicians support the extremists and try to push their views via legislation, thereby legitimizing and empowering them. The Sagebrush Rebellion, in other words, has been co-opted: militarized in some places and politicized in others. Politicians, militants, sheriffs and others from across the right-wing spectrum have, over the last few years, found common cause, attending conferences, rallies and events together, and putting their support behind a variety of agendas.

For a more detailed (and interactive) graphic of these connections head over to High Country News by clicking here.

Lastly, the report highlights the two-way consequences of this prolonged dissent. Unfortunately, the steady escalation in tension has triggered the militarization of our should-be park rangers as well. The BLM’s Arms Race On the Range, by Marshall Swearingen, explores how the Bureau of Land Management has undergone radical shifts of its own in response to the growing opposition against them.

The BLM badged its first 13 rangers in 1978 for a specific purpose: To rein in illegal off-road vehicles in the California desert. They modeled themselves after Park Service rangers — brown wool trousers, khaki shirts and all — and carried only pistols. When the program expanded beyond California in the late ’80s, “everybody thought the rangers were about recreation management,” says Dennis McLane, who joined in 1979 and became the BLM’s first chief ranger in 1989. As the rangers trickled across the West, he says, they quickly confronted other crimes: archaeological looting, timber theft, illegal dumping.

But a lot has changed in 35 years…

As the West changed, so did the rangers. Bulging cities like Los Angeles and Las Vegas pushed urban crime onto the public land. Off-roading in the desert sometimes degenerated into drug- and alcohol-fueled riots with stabbings and other violent crime. “We were seeing more and more automatic weaponry,” says Cris Hartman, hired as a ranger in 1984. She recalls a series of controversial equipment upgrades: shotguns in the ’80s; semi-automatic rifles in 1992; and high-powered assault rifles in the early 2000s, after she’d left the BLM for the Forest Service, where she observed a similar pattern. Still, “the sheriffs were always ahead of us,” in terms of weaponry, she says.

Bureau of Land Management rangers stand guard as protesters gather at the gate of the BLM’s Bunkerville base camp after the roundup of some of Cliven Bundy’s cattle from public land in April 2014. (Photo/Caption: Jim Urquhart/Reuters)