Farming Pathogens: An Evolutionary Biologist on the Links Between Big Ag and Disease

Rural America In These Times

Intensive or monoculture farming — the industrial agricultural practice of producing way too much of one thing in order to maximize yield and profits — has serious global economic and ecological consequences. This, for the most part, is common knowledge. Despite all the patents, land grabs, pesticides and antibiotics, hunger and insufficient nutrition remain a problem for many people in the United States and around the world. But “Big Ag” isn’t just stiffing farmers, confining animals, polluting water supplies, failing to “feed the world” and, in the process, making a lot of money for a few corporations. According to Rob Wallace, it’s creating entirely new “agro-environments” for deadly pathogens to thrive.

Wallace is an author, evolutionary biologist and phylogeographer — someone who studies the forces behind the geographical spread and distribution of various living things, from viruses to mammals. His most recent book, Big Farms Make Big Flu: Dispatches on Infectious Disease, Agribusiness and the Nature of Science, tracks the ways influenza (bird and swine flus for example) and other pathogens are emerging within “an agriculture controlled by multinational corporations.” His blog, Farming Pathogens, explores the intersection of economics, food production, the environment and public health. In his words, the project is concerned with “disease in a world of our own making” and follows everything from “agriculture, infections, evolution, ecological resilience, dialectical biology, and the practice of science.”

In his latest post, “Ten Theses on Farming and Disease,” Wallace hashes out why industrial agribusiness is “a scam” for farmers. He also makes the case that the epidemiological risks it poses could eventually kill a lot of people. The solution, he argues, is an end to the industrial food commodity paradigm, and the implementation of biodiverse, local, agroecological food systems.

Rob Wallace, a phylogeographer, writes:

Every once in a while, we have to take a stab at putting all the pieces together. In some ways these ten theses on farming and disease only touch on what I, and others, have been saying all along. But there’s a growing understanding of the functional relationships health, food justice and the environment share. They’re not just ticks on a checklist of good things capitalism shits on. Falsifying Hume’s guillotine, embodying a niche construction at the core of our human identity, justice and the ecosystem appear to define each other at a deep level of cause and effect.

1. Contract farmers around the world are suffering cost-price squeezes. Producers are at one and the same time suffering increasing input costs and low or falling prices for their goods at the farm gate. The farmers are forced to chase an economic Red Queen. Individual farmers must increase production if only in an effort to cover for low prices that increases in production across farms helped depress to begin with.

2. The squeeze is a scam agribusiness is running on farmers. In enforcing high farm output, companies are seeking gluts that cheapen ingredients for their processed product lines. High output, producing food beyond global consumer demand, is also about making money off farmers contractually obligated to buy synthetic inputs they don’t need to grow us enough food.

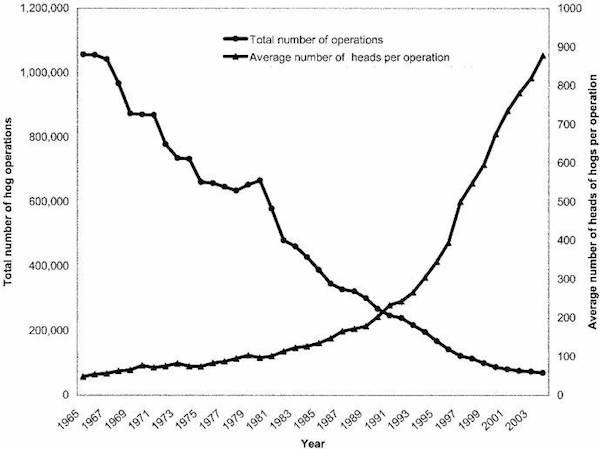

3. The gap between cost and price, also a form of labor discipline, forces many farmers out, leading to plot consolidation as those smallholders and mid-level operations still left buy up abandoned land, banking on economies of scale, debt-financed mechanization, and appreciation in land equity to pull them through the artificial price squeeze.

Consolidation in hog operations from 1965 to 2003. (Source: Farming Pathogens)

4. The resulting increases in farm size and debt, declines in crop and livestock diversity, and lengthening commodity chains across expanding food geographies depress rural resilience to disease outbreaks associated with agricultural production. By their immense monocultures, crop and meat producers alike are also industrializing pests and pathogens, ramping up outbreak frequency, scale, and deadliness. In short, industrial production offers less protection against a growing epidemiological danger of its own making.

5. In this system, controlling outbreaks means first and foremost protecting the economic model making agribusiness so much money. Actual farming practices — how food is grown across the landscape — are allowed to change only to the extent they contribute to new ways of expropriating the farmer. That means, even the problems of agribusiness production, disease included, become just another way to make money off farmers.

6. Corporate buyers at the farm gate demand producers control outbreaks arising inevitably out of monoculture production with pesticides and pharmaceuticals many of these corporations — chemical or pharmaceutical companies first—sell. No solutions — say, agroecological diversification or regional mosaicism — are to be pursued outside the commodities the companies buying the produce dictate.

7. Agricultural pests and pathogens — with many of the livestock and poultry diseases capable of spilling over into human populations — don’t care to cooperate with such an arrangement. They don’t read company memos or respect quarterly earnings. That isn’t to say they don’t like the model of global monoculture. In fact, if you’ll excuse the anthropomorphism, a wide array of disease agents prosper by it. The business model helps many pathogens and pests to spread across the world, meeting new potential hosts they wouldn’t otherwise, along the way often evolving greater infectiousness and deadliness.

8. So the only way to stop the next deadly pandemic to emerge directly out of livestock or poultry or indirectly out of wild animals subjected to Big Ag-driven deforestation is to end capitalist agribusiness as we know it.

9. Land ownership and the state of farmer autonomy and the control local communities can exert over configuring food landscapes are fundamentally linked to the epidemiological fates of our deadliest diseases. If we want to keep the next pandemic, the next Ebola or bird flu or Nipah virus, from killing a billion people, agriculture must be returned to farmers and their local supporters at both the level of the individual farm and as a collective enterprise across diversified landscapes.

10. Public trusts and cooperative models organized around multifunctional agroecologies addressing the needs of food and farmer and environment all together are our best protection against the worst of the new diseases.

(“Ten Theses on Farming and Disease,” was originally published on Farming Pathogens and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the author.)