Corporations Know Income Inequality Will Sink Us All. Here’s Why They Just Can’t Help It.

Wallace Hopp

Scorpion met Frog on a river bank and asked him for a ride to the other side. “How do I know you won’t sting me?” asked Frog. “Because,” replied Scorpion, “if I do, I will drown.” Satisfied, Frog set out across the water with Scorpion on his back. Halfway across, Scorpion stung Frog. “Why did you do that?” gasped Frog as he started to sink. “Now we’ll both die.” “I can’t help it,” replied Scorpion. “It’s my nature.”

This centuries-old parable, which has been retold by Orson Welles and many others and sometimes refers to a turtle rather than a frog, is usually meant to show how a bad nature cannot be changed — even if self-interest and preservation demand it.

It’s also an apt metaphor for the growing scourge of income inequality, one of the defining issues of our age.

A standard explanation for why income inequality is increasing, to borrow a quote from Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, is that “wealth begets power and power begets more wealth.” That is, because the rich and corporate CEOs use their influence to promote their self-interest, inequality is built into the very DNA of capitalism. And to return to our metaphor, the rich scorpions sting the rest of us — by exacerbating income inequality through pay policies, stock buybacks and other actions — because it’s simply their nature.

But there’s plenty of evidence income inequality undermines the economy and, as a result, harms companies and the wealthy too. Eventually, we all sink together.

A growing body of research in the emerging area of “positive organizational scholarship” suggests a different lesson from the scorpion fable: everyone can benefit if they work together. That is, companies can invest in their workers, help reduce income inequality and make more money, all at the same time.

But they need a new perspective to see how.

Age of rage

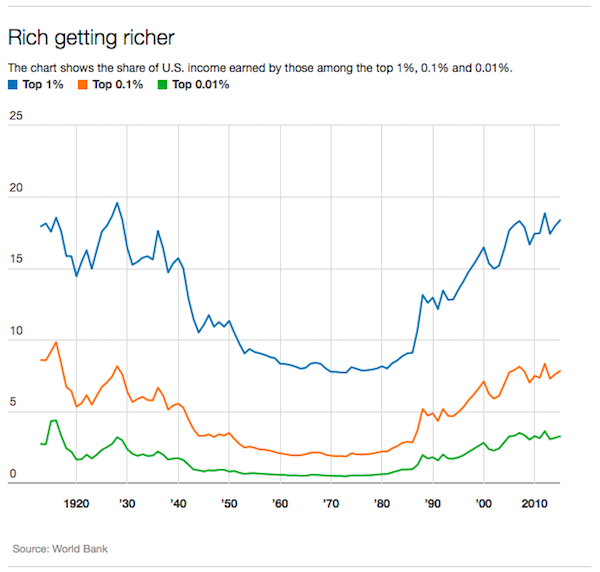

The issue of income and wealth inequality received a lot of attention on the campaign trail, as candidates argued whose policies would be most effective at lifting wages of the working class. And no wonder. The percentage of total income received by the top 1 percent of earners in the U.S. has risen from under 8 percent in the 1970s to over 18 percent today. The percentage of total wealth held by the richest 0.01 percent (the elite 1 percent of the 1 percent) has soared from under 3 percent to over 11 percent over this interval.

For an interactive version of this graphic, click here. (Source: World Bank / The Conversation)

We haven’t seen extremes like these since the start of the Great Depression. So the response, consisting of speeches by political candidates, articles by pundits, research by academics and angry outbursts by the public, is hardly a surprise.

How inequality hurts growth

Let us consider two important ways income inequality undermines the economy: (1) by diminishing worker motivation and (2) by reducing the velocity of money.

The demotivating impact of income inequality occurs when workers see the gains of productivity going almost entirely to executives. Since 1973, productivity has increased by over 73 percent, while (inflation-adjusted) hourly worker pay has risen by only about 11 percent and CEO compensation has soared by 1,000 percent.

Who can blame people for being reluctant to work harder when they know the proceeds will go to someone else? Extensive behavioral research has shown that people will forego personal gain to prevent outcomes they perceive as unfair. In work settings, this leads to demotivated workers working below their potential, even when it leads to smaller raises or bonuses. The result is reduced productivity, lower quality and less creativity, all of which undermine corporate profit and economic growth.

Another way inequality affects the economy is by reducing the velocity of money by shifting cash to people who spend it more slowly. Working-class people who are stretching to make ends meet spend their income quickly — usually pretty much all of it— while wealthy people whose resources exceed their immediate needs tend to save substantial portions of their income.

Consequently, whenever a company takes a dollar out of the hands of a worker and puts it into the hands of an executive or investor, the number of times that dollar will be spent in the economy is reduced. The result is less business for capitalists and less employment for workers.

These two observations imply that policies that decrease income inequality also bolster the economy. Since this benefits both rich and poor, such policies offer opportunities for the rich, and the businesses they control, to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem of income inequality.

Henry Ford’s famous $5-a-day

The most straightforward opportunities are workforce investments to increase motivation and productivity of workers.

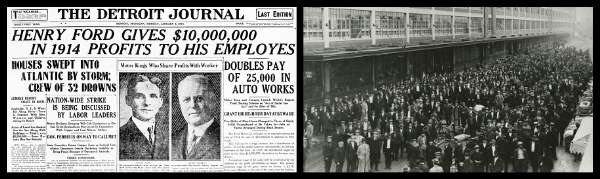

This is what Henry Ford did a century ago with his famous US$5 a day wage—at a time when typical manufacturing wages were about $2.25 a day — which he called “one of the finest cost-cutting moves we ever made.” In the present day, businesses ranging from tiny cleaning company Managed by Q to giant retailer Costco are using high wages as part of what Zeynep Ton of MIT calls a “good jobs strategy” to drive productivity, quality and profits.

The day after the Ford Motor Company announced its employees would make $5 a day, 10,000 people showed up to the plant in Highland Park, Mich. to apply for jobs. (Images: The Henry Ford Collection)

But isolated actions by individual companies are too small to have a significant impact on the velocity of money across the economy. To realize the full economic benefit of some income inequality-reducing policies, businesses need to implement them collectively.

This happened to a degree with Ford’s high-wage policy. Despite the legend that he raised wages to enable his workers to buy his cars, Ford’s original goal was to improve retention and productivity. However, when other employers followed suit, their collective wage increases produced a working class that could buy more cars and more of everything else.

Stock buybacks make income inequality worse

A contemporary example of a situation that calls for collective action is the increasingly common practice of stock buybacks.

These are used by public companies to boost their stock prices by reducing the total number of shares, which in turn increases earnings per share. However, because this enhances stock-based executive compensation without benefiting workers, stock buybacks amplify income inequality.

An alternative for boosting stock price without aggravating income inequality is investing in worker compensation as part of a productivity enhancement strategy. But, since productivity investments take time to produce results, it is likely that the buyback strategy will generate a greater increase in stock price, and executive compensation, at least in the short term. So, from a pure self-interest perspective, management has incentive to adopt the buyback strategy rather than the workforce investment strategy.

The fact that stock buybacks exceeded $500 billion in 2015 suggests that many businesses made precisely this choice.

Stop stinging the frog

Unfortunately, because buybacks divert money away from investments in productivity without improving firm performance, they ultimately lead to less profit, fewer jobs, lower wages and a smaller overall economy. Furthermore, if other firms are using them to boost executive compensation, a company that wants to recruit and retain top managerial talent will be seriously tempted to use buybacks as well.

An option for breaking this economically destructive cycle, which almost never gets considered, is for firms to lobby to take the buyback option off the table for everyone. If, for example, stock buybacks were restricted, as they were prior to 1982, management would have greater incentive to make genuine investments in their businesses, including in their workforces.

In addition to producing productivity gains within businesses, the increase in worker compensation would result in a velocity-of-money induced stimulus to the economy as a whole. The combined effect over time could even be large enough to make both executives and workers better off than they would be under the buyback strategy.

While collective lobbying for sensible regulations may sound like business heresy — in a world where corporate lobbying usually seeks narrow favors or to stymie regulations in general — it is a rational response to a situation in which legal and profitable actions by individual companies create negative consequences, or “externalities,” on the rest of the economy, and thereby wind up hurting the companies themselves.

Metaphorically, such scenarios are analogous to a large number of tiny scorpions (businesses) riding across the river on a giant frog (economy). When a single scorpion stings the frog, it derives pleasure from doing what comes naturally and barely harms the mammoth frog. But when every scorpion does the same, the frog dies and so do all the scorpions.

But humans aren’t scorpions, so we can choose to stop the self-destructive stinging and allow everyone to cross the river.

Disclosure statement: Wallace Hopp does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above. “How Corporate America Can Curb Income Inequality and Make More Money Too” was first published by The Conversation under a Creative Commons License.

Mr. Arkadin, a mysterious tycoon played by Orson Welles in the 1955 thriller of the same name, regales his house guests with the fable of “The Scorpion and the Frog.” The film was also released under the title “Confidential Report.” (Video: YouTube / Warner Bros.)