Why Cutting Up Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is a Bad Idea

Joseph Bullington

Driving north through the Grand Staircase region of the Colorado Plateau is like travelling in a time machine. For more than 100 miles, as the Staircase climbs from south to north, from low elevation to high, it climbs also through time — 245 million years captured in the layers of rock. The epochal steps of the Staircase are marked by altitude, by age and by color, with the oldest rock at the bottom and the youngest at the top:

the Pink Cliffs.

the White Cliffs,

the Vermilion Cliffs,

the Chocolate Cliffs,

The Grand Canyon,

Here, erosion has carved a life-sized cross section from the Earth’s crust and provided a chronological, color-coded display. More recent history, too, has left its mark in the rock: 6,000-year-old petroglyphs haunt these canyons like echoing voices.

In my mind and on maps, however, the place stands out mostly for what it lacks: those preeminent purveyors of environmental destruction and fast food chains known as highways. Anyone who has made the drive will know what I mean. From the town of Page on Arizona’s northern border, Moab, Utah lies only 150 miles northeast as the crow flies.

As the car drives, however, it’s nearly twice as far: to the east, a 275-mile arc through the Navajo Nation; to the west, a 400-mile zag through Bryce Canyon and Capitol Reef. In the middle, the obstacle circumscribed by this noose of asphalt: 1.9 million acres of desert wilderness protected, until now at least, within the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. The last area in the continental United States to be mapped, the Grand Staircase remains one of the last and largest stretches of wild land in the 48 states.

President Trump’s Dec. 4 monument proclamation will change that.

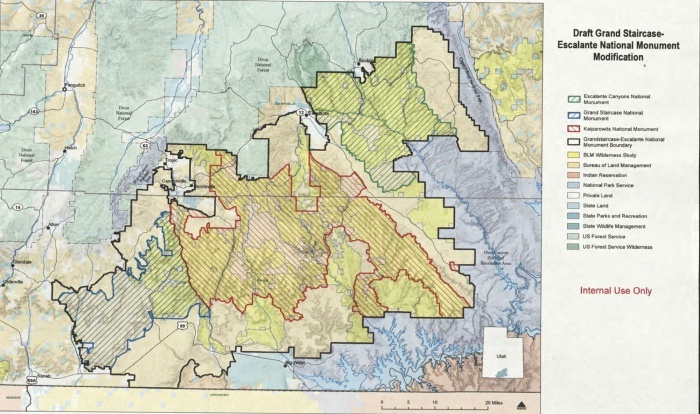

The monument’s original protections prohibit the expansion or development of roads within its boundaries. But like Bears Ears National Monument, its more famous neighbor to the east, Trump’s plan drastically shrinks Grand Staircase-Escalante — reducing it in size by nearly half and chopping it into three, smaller monuments: Grand Staircase, Kaiparowits and Escalante Canyons.

Scott Groene, executive director of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA), says, “You’re liable to see immediate fights about off-road vehicle use and the counties trying to break apart this wild country with new and improved roads.”

Indeed, the maps of the Trump plan show a large strip of land conspicuously excluded from monument protection, severing the northeastern Escalante Canyons section from the bulk of the monument lands. That strip, it so happens, contains a washboarded dirt road — a road the state of Utah and the local counties of Kane and Garfield hope to pave.

An old Mormon pioneer trail, the road runs 63 miles from the town of Escalante to Arizona’s Hole-in-the-Rock, where the modern road ends and where the pioneers lowered their wagons to the canyon floor. Here, Utah proposes to designate a state park and pave the road to increase tourist development.

“Paving it would explode the amount of use,” says Mathew Gross, media director at SUWA. “You’d see a tremendous growth of industrial tourism.” That happened at Arches, Canyonlands and the Grand Canyon, to name a handful of cases in the area. So few stretches of roadless, wild land remain, Gross thinks the very rarity of it makes it worth defending. That, he says, and the increasingly rare “joy of having to work to explore something.”

The land grab myth

When he ordered the review of national monuments in April, President Trump adopted the language of Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) and other avowed enemies of federal land management: Past monument designations like that of Grand Staircase-Escalante, Trump said, were “a massive federal land grab.”

This is a good story, and one that plays well in much of the rural West. The problem is, it’s utterly false. The vast majority of the lands in Grand Staircase-Escalante were federal public lands before the monument was created in 1996, and the lands now excluded from monument status will remain federal public lands. (The feds bought out the few state inholdings in a 1998 land exchange.)

This is important to point out because some monument opponents and supporters alike seem to be either confused or lying. For example, in response to Trump’s monument reduction the outdoor clothing company Patagonia presented a blacked-out home page on its website bearing the words “The President Stole Your Land,” in large white letters — a message as arresting, provocative, and misleading as the “Feds Stole Your Land” story.

When presidents create national monuments, a power vested in them by the Antiquities Act of 1906, they confer increased protections on federal lands. Under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA), the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages federal lands for “multiple uses” — for commercial uses like livestock grazing and mineral extraction, for recreational uses like hunting and hiking, and for conservation of ecosystems and historical artifacts. In a national monument (in theory, at least) all other uses of the land are subordinated to the demands of conservation.

When a national monument is designated what changes is not the ownership of the lands but the level of protection for ecosystems and artifacts. By reducing the size of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears, Trump’s national monument proclamation strips these protections from some two million acres of land — the largest rollback of land protections in U.S. history.

Geology politics

The 1,600 square-mile Kaiparowits Plateau in Grand Staircase-Escalante contains one of the most complete fossil records of the Late Cretaceous period, when the region was a tropical rainforest. Since 2000, 20 new species of dinosaur have been discovered on the monument.

According to the monument website, the rock layers “tell a 30 million-year-long prelude story to the catastrophic end of the dinosaurs.” However, the same geologic forces that captured and preserved layers of dinosaur bones also captured layers of densely accumulated plant matter, which were eventually pressurized into coal. “The two resources are inherently mixed up together,” writes Rebecca Worby for High Country News, “both geologically and politically.”

When President Bill Clinton designated the monument in 1996 — to preserve its paleontological treasures, its biological diversity, and its character as a large and wild place — the order headed off plans for a coal mine on the Kaiparowits. The government bought out the mineral leases from the company, Andalex Resources, for $14 million. All lands in the new monument were removed from the mineral leasing market and existing oil and gas leases were suspended. Road development and improvement were banned, and some backcountry roads and ATV routes were closed, infuriating some locals.

Under the Trump plan, a large portion of the Kaiparowits will again be opened to potential fossil fuel development. A leaked map of the new plan shows the Trump monument boundaries redrawn in a strange hourglass shape that excludes much of the Kaiparowits coal deposits from monument protection. However, SUWA Executive Director Scott Groene thinks that, for now at least, coal development there probably isn’t economically feasible.

He puts it this way: “From the top of Kaiparowits, you can see the Navajo coal plant, which is scheduled to be shut down in two years.” The Navajo Generating Station, which is connected by an elaborate infrastructure of conveyor belt and electric train to the Kayenta coal mine on the Navajo Reservation, is scheduled to close in 2019 due to the cheapness of electricity generated from natural gas.

The majority of the authorized oil and gas drilling leases suspended by the monument’s 1996 designation are concentrated along Escalante’s northeastern edge, where the 1996 monument boundaries abut Capitol Reef National Park. That area is mostly cut out of Trump’s redrawn monument boundaries, which means many of those leases could go back online while other excluded lands are put up for oil and gas lease.

The grazing issue

Some people see the Grand Staircase-Escalante not as empty, pristine wilderness but as lands from which they make their living, and have for generations. According to Ethan Lane, executive director of the Public Lands Council (PLC), a D.C. based group that advocates for ranchers’ use of public lands, many landowners in the Grand Staircase-Escalante area depend on those federal lands to graze their cattle. The PLC praised the Trump administration’s decision to shrink the monument because, according to Lane, local ranchers were not adequately consulted when President Bill Clinton created the monument in 1996.

“In some of these western communities you have a lot of moving parts,” Lane says. “You have a lot of conservation efforts going on on the ground on behalf of local landowners that really depend on those federal lands that are adjacent to them. When you haphazardly change the status of that resource without evaluating that, the ramifications can be intense.”

In his proclamation designating the monument, Clinton addressed grazing: “Nothing in this proclamation shall be deemed to affect existing permits or leases for, or levels of, livestock grazing on Federal lands within the monument; existing grazing uses shall continue to be governed by applicable laws and regulations other than this proclamation.”

Lane claims the federal government did not live up to this promise. According to the grazing figures he has put together, 30 percent fewer cow-calf pairs were permitted to graze on federal lands in the monument in 2013 compared to grazing levels before the monument was designated.

Laura Welp, who worked as a botanist for the monument from 2001 to 2005 and is now an ecosystem specialist for the Western Watersheds Project, thinks that the monument administration has permitted extensive grazing on monument lands, at the expense of its conservation mission. The monument’s management plan, signed in 1999, asserts the duty of the monument administration to manage grazing to meet the standards of rangeland health required by BLM regulations.

The plan called for an evaluation of grazing allotments and a new grazing plan when the assessment was done. Welp spent two years on the monument gathering data about ecosystem health and the impacts of grazing. In the end, she says, the data were not used and no new grazing plan was put in place. Grazing has continued on the monument, she says, based on evaluations from the 1970s.

“They had a beautiful management plan that could have been really innovative,” she says, “and in regards to grazing, at least, it’s been ignored.” Staff at the Grand Staircase-Escalante headquarters tell me they were instructed not to talk to the press, and directed inquiries to the BLM state office, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

According to Lane, the debate isn’t about whether to preserve natural resources in the West — it’s about process. He thinks the Antiquities Act itself is flawed, that it gives presidents too much power to suspend lands from multiple-use. Monument supporters, too, are concerned with process. They argue that only Congress, not the president, has the power to remove monument designations. But clearly more is at stake here than who decides whether wild lands are preserved — at stake is an actual wild place.

The shrinking of Grand Staircase-Escalante is not symbolic — it’s more than a simple case of Trump undoing Obama’s legacy with an executive order, something that could be re-visited again when the pendulum of power swings back to the Democrats.

Once roads are established, they tend to be maintained. And once a wild place is carved up, we don’t get it back.

Joseph Bullington grew up in the Smith River watershed near White Sulphur Springs, Montana. He is the editor of Rural America In These Times.