The “Identity Politics” Debate Is Splintering the Left. Here’s How We Can Move Past It.

We must redefine “identity politics,” because the debate about it is mostly wrong. We can start by recognizing that Clintonian identity politics aren’t intersectional—they’re racist.

Thea N. Riofrancos and Daniel Denvir

Donald Trump won in no small part thanks to crucial votes cast by downwardly mobile white people across America’s shattered manufacturing belt. The media narrative describing a massive rightward shift by these voters might be an oversimplification. But the fact remains that a big chunk of a demographic that supported Barack Obama in 2012 voted for Trump or a third party this year, or else stayed home. As a result, a renewed debate over whether to mobilize the “white working class” is roiling the Democratic Party (and those to its left). The New York Times framed the question like this: “Should the party continue tailoring its message to the fast-growing young and nonwhite constituencies that propelled President Obama, or make a more concerted effort to win over the white voters who have drifted away?”

We might instead frame it like this: People from left to center are engaging in heated, rarely helpful and often confused conversations about “identity politics” that present false choices about how to move forward. In the wake of Trump’s inauguration, the debate has become somewhat muted as left to liberal resistance has coalesced into persistent, multifaceted and enormous nationwide protest movements. Disputes, however, will no doubt reemerge and continue to fracture the left wing of this resistance. While internal debate is productive, a united front is crucial. At issue is not only the future of the Democratic Party but, more broadly, the strategies of political resistance and social mobilization under a Trump presidency and the future of an independent Left that has now set its sights on winning power.

Some liberal writers, like Rebecca Traister, are concerned that appealing to white workers will ultimately distance the Democratic Party from the “women and people of color” who make up its base. Meanwhile, other liberals, hostile to “identity politics” but by no means leftists — intellectual historian Mark Lilla, for example—argue that “American liberalism has slipped into a kind of moral panic about racial, gender and sexual identity.” On the socialist left, Shuja Haider and others skewer “identity politics” for dividing the collective “we” necessary for revolutionary politics.

The first argument assumes that a focus on class entails a narrow focus on the grievances of white workers and the abandonment of a diverse Democratic constituency; the second and third that narrow identitarian appeals undermine the more encompassing identity (“Americans as Americans” per Lilla; the “working class” for socialist critics) required for a successful liberal or left coalition. Ironically, despite their vehement disagreement over whether “identity politics” should be the mobilizing strategy, all three positions presume the same neoliberal framing of identity politics — positing a zero-sum game between individual groups with narrow and mutually opposed interests — that has guided the liberal establishment for decades.

All three arguments are misconceived because they construe identity as atomistic, and thus misunderstand the relationship between what they call “identity” and class. Contemporary American capitalism is a system structured by race, gender and unequal citizenship — from housing segregation to the unremunerated second shift worked by women to the growth of the low-wage service sector and its impact on immigrants and women and on men displaced from manufacturing. Those who are marginalized on account of their race, gender or immigration status — or some combination thereof — are disproportionately more likely to be poor and working-class. A working-class political program should buttress rather than exclude the struggles of marginalized groups.

By pitting race and gender against class, some liberals’ eschewal of class-based mobilization and others’ dismissal of “identity politics” ensure electoral defeat for the Democratic Party. And insofar as this zero-sum understanding of identity resonates among leftists committed to class struggle, it threatens to sow divisions among those working towards economic and social justice — divisions we can scarcely afford given the militaristic, xenophobic, and plutocratic agenda pursued by the White House.

A clarification of terms, and of history, is in order.

“Identity politics” vs. “neoliberal identity politics”

Contra anti-“PC” crusaders like Lilla, the problem is not that liberals are excessively focused on the rights of queer and non-white people — as Lilla claims in a mean-spirited aside targeting transgender people, that liberals spend too much time focusing on bathrooms. Nor, in its left variant, is the problem that a universally conceived class identity ought to supersede particularistic group identities.

Achieving a sense of shared class identity, as socialists from Karl Marx to E. P. Thompson have long made clear, has always proved a challenging task. And not just because of the way capitalism drives a wedge between workers along lines of race, gender, religion and ethnicity — from white male-dominated craft unions’ exclusion of women and people of color to white supremacy stymying unionization drives in the South. Capitalism also fragments working-class identity by pitting workers against one another as they compete over jobs and wages, and hierarchizes them by trade and rank. It downplays people’s role as workers and valorizes their identities as individual consumers. Capitalism, and not struggles for racial or gender justice, is what preemptively undermines the potential for shared and cohesive class identity among the working-class majority.

Indeed, “identity politics” isn’t the problem at all. The debate shouldn’t be about whether “identity politics” is a good or bad thing, but rather over the term’s very different and too rarely explicated meanings. As suggested by the recent proliferation of references to the “white working class,” identity politics does not exclusively refer to groups marginalized on account of their race or gender. Rather, identity politics is implicated in all mass politics. People interpret their conditions and their interests in relation to historically constructed collective identities. Whether it be a black McDonald’s worker who thanks to Fight for 15 comes to understand the links between poverty wages and mass incarceration or a white machinist who witnesses a boss use a co-worker’s immigration status as leverage against a unionization drive, identities are never etched in stone but contingent on political and social context. Contra leftists who implicitly assume that class identity would magically cohere if workers were not divided by race or gender, the success of any political movement depends on both resonating with existing identity categories and, as struggles and conditions evolve, forming new ones. For leftists, then, the critical issue is not whether “identity” is the basis for politics, but rather how identities are articulated, and whose identities are being mobilized, in what ways, and toward which ends.

The neoliberal variant of identity politics ascendant in recent decades is successful in articulating and mobilizing atomized identities, but it is an obstacle to building broad movements grounded in solidarity because it regards those identities as mutually opposed units. This politics, adopted as a political strategy by segments of the Democratic establishment and uncritically reinforced by its critics, is radically non-intersectional. It assumes that social groups — say, gay or black — are homogeneous monoliths with uniform interests. And when class isn’t taken into account, socialist critics rightly note that “identity politics” has become a vehicle for the interests of elite leaders who substitute diversity in the White House and on Wall Street for substantive justice. Poor black people and poor white people both face increasing economic precarity and thus share many of the same grievances. Conversely, wealthy black elites share economic interests with wealthy people as a whole — interests opposed to those of the much larger number of black people who are economically marginalized. The same goes for wealthy women or wealthy LGBTQ people.

The fact of intersecting identity need not devolve into infinite fragmentation. Rather, intersections can orient individuals and communities toward others precisely through those points of particularity and difference — nodes that, when linked, can strengthen people’s bonds instead of breaking them. This debate is not merely semantic. For the last 25 years, neoliberal identity politics has not only hurt poor and working class people but confused the Left’s explanation as to why it has happened.

Bill Clinton, the architect of neoliberal identity politics

Though Trump rode nationalist right-wing white identity politics into the White House, the reincarnation of the Democratic Party under Bill Clinton helped lay the groundwork. Clinton’s master strategy of triangulation (out-righting the Right) coupled neoliberal economics with mass incarceration and sold both with racially coded rhetoric. This strategy helped consolidate the “white working class” (at the time, figured as the white middle class because far more working people identified as middle-class than they do now) as an identity — and as a reactionary political constituency.

In the 1990s, Bill Clinton employed anti-black racism to appeal to the “Reagan Democrats” who had been exiting the party in part due to Republicans’ by-no-means-entirely-Southern Southern Strategy — a strategy abetted by Jimmy Carter’s anti-labor agenda. This was the very same demographic group that Clintonites today accuse the Left of appealing to on the grounds of the narrow single-issue of class struggle. Responding to and drawing on the rising conservative movement, Clinton outflanked the right by backing welfare reform, the war on crime and a crackdown on immigrants. He deployed racialized and gendered language to contrast the culture of “dependency” (implicitly associated with black people, especially women) with “work,” resonating with the pre-existing Reaganite trope of “the welfare queen” and racially dividing the working class between honest producers and beleaguered taxpayers on one side and undeserving poor takers on the other.

The increasing identification of poverty and welfare with African Americans, and the stereotyping of black people as lazy and sexually irresponsible, precipitated welfare’s growing unpopularity. Perversely, formal racial equality facilitated neoliberal identity politics by blaming poor black people for their problems (what did they have to complain about now?) as well as the ascension of a black elite unconcerned with the condition of the incarcerated poor.

On mass incarceration, Clinton crowed that “it’s three strikes and you’re out.” On immigration, Clinton boasted of signing “a tough anti-illegal immigration law protecting U.S. workers.” Regarding welfare, Clinton condemned a system that “undermines the basic values of work, responsibility and family, trapping generation after generation in dependency and hurting the very people it was designed to help” (what Paul Ryan would later call “offering people…a full stomach and an empty soul”).

People of color bore the brunt of policies, enacted at the local, state and federal level, which disproportionately subjected them to police violence, incarceration, poverty and deportation — with drastic social and economic consequences. At the same time, Clinton’s race politics provided him with the political cover to push through an economic agenda that prioritized finance over labor and so was detrimental to working class people as a whole. Of course, the race politics were also economic at their core: welfare reform provided employers with an expanded and unprotected low-wage labor force while mass incarceration locked up huge numbers of systematically disemployed young men and made them invisible to the public.

Welfare reform and the war on crime, though justified by appeals to racist stereotypes, ultimately harmed many lower income and working class whites. As Ian Haney-López and Heather McGhee write at The Nation, racism has been the key tool that Republicans and neoliberal Democrats have used not only to advance racist policies but to attack labor and shred social welfare protections across the board: “The reactionary economic agenda made possible by dog-whistle politics is responsible not just for the devaluing of black lives but for the declining fortunes of the majority of white families.” Welfare reform’s politics — presenting economic success and failure as a reflection of individual morality — would smooth the way for a broader assault on the collective underpinnings of human well-being, from George Bush’s “ownership society” through Gov. Scott Walker’s decimation of organized labor in Wisconsin. These well-funded and tightly organized right-wing attacks on unions and the poor have been facilitated by the collapse of left-of-center working class institutions and the erasure of class as a point of common interest.

Divide and convince

Clinton, of course, still felt black people’s pain. As political scientist Claire Jean Kim argues, Clinton initially sought support from whites by symbolically rejecting blacks (running against “racial quotas,” making a point of presiding over the execution of a mentally-disabled black man and rebuking Jesse Jackson vis-a-vis a misleading denunciation of rapper Sister Souljah) and then later employed a strategy of “placating blacks for their relative lack of policy influence with largely symbolic gestures.”

Clinton kicked off his second term by apologizing for the Tuskegee experiments (he considered backing a bill formally apologizing for slavery, Kim writes, but decided not to: it didn’t poll well) and launched the One America in the 21st Century initiative, a national conversation about race — neoliberal elites love conversations about race — that emphasized race relations rather than racism and dialogue over justice. He also appointed, Kim writes, a record number of women and people of color to his cabinet, the judiciary and other positions.

It’s a form of symbolic diversity politics still very much in vogue, as seen in the Hillary Clinton campaign’s behind-the-scenes push to leverage friendly woman and non-white writers to attack Sanders, exposed in John Podesta’s hacked emails. Those emails also showed former Labor Secretary Tom Perez, an Obama ally challenging Berniecrat Rep. Keith Ellison for DNC chairperson, pushing the Clinton campaign to change the “narrative … from Bernie kicks ass among young voters to Bernie does well only among young white liberals” — a narrative that, given Sanders’ strong support from young people of any color, was false but resonant for those primed to believe it.

Black faces in high places, the neoliberal take on “some of my best friends are black,” still passes for racial justice in many circles. Or as a New York Times headline put it recently: “Trump Diversifies Cabinet.”

After the Democratic Party’s crushing defeats under Reagan, Bill Clinton’s version of identity politics did win modest pluralities of white working class votes and temporarily slowed their slide to the right. But this strategy sacrificed the future of the Democratic Party — not to mention the lives of many who were impoverished or imprisoned — for short-term electoral gains. In the long run, Trump and the Republican Party reaped the fruits of Clinton’s purported genius: It was the Right, of course, that would ultimately profit from the Democrat’s appeal to white reaction.

Bill Clinton addressed working-class whites as whites rather than as people who shared economic interests with working-class black and brown Americans, all while undermining both their quality of life and their main source of political power: organized labor. The financial and economic policies his version of identity politics abetted caused the percentage of workers who were union members to continue its slide during the Clinton era from 16.1-percent in 1990 to 13.5-percent in 2000. This was ultimately self-defeating: Labor unions served as both the institutional underpinnings of white working class ties to the Democratic coalition and the framework for interpreting their lives through the lens of their class interests.

Clinton’s strategy was intended to woo white voters by severing the Democratic Party’s perceived allegiance to black interests, but it didn’t stop the right from making its Nixonian case to white workers that the Democratic Party represents an elite-underclass alliance set against hard-working and taxpaying (read: white) Americans. Instead, by highlighting diversity while pushing an anti-worker agenda, the strategy fractured the Democratic coalition and facilitated the right-wing’s ascendance. When the credit bubble popped and Clinton’s economic golden age was exposed as a fraud, Trump was lying in wait to explain what went wrong.

Neoliberal identity politics today

Obama modulated the Clinton model without breaking it. He offered modest reforms to the criminal justice system, orchestrated both mass deportations and then protections from deportation for some immigrants, boosted financial regulation while failing to attack Wall Street power head on. He communicated his policies not through the lens of particular identities or class but rather by portraying America as united by hope — something along the lines of what Lilla proposes. It was the friendlier, cathartic inverse of George W. Bush’s post-9/11 message that Americans stood together in their vulnerability before and stoic resolve against terrorism.

For Obama, this approach reaped political rewards — he left office with an approval rating of 59 percent — but the lack of a coherent program (combined with restrictive voter ID laws and gerrymandering) allowed the Democratic Party to be wiped out at the state and local level. Over the last eight years, the problem with the party hasn’t been embracing identity politics too fervently, as Lilla contends, but not constructing a truly intersectional identity politics aligned with a concrete, broadly conceived and clear policy program that can win elections without a uniquely skilled communicator in the White House.

Enter Hillary Clinton. She and Bill, as Hillary’s defenders are quick to note, are not the same person. But it is obvious that they are the most powerful political partnership of our generation, and each has been the other’s top advisor. Hillary, after clinging tightly to her husband’s centrist image for years in the White House and the Senate — and then recycling his racially coded rhetoric in her 2008 primary contest against Obama — recognized that Bill’s dog whistling was no longer a winning strategy in a Democratic primary. In the current political context — marked by the emergence of Occupy, the Movement for Black Lives and Bernie Sanders — — she shifted course to appeal to an increasingly left-leaning party electorate. However, rather than articulate a comprehensive and encompassing critique of America’s ruling political-economic regime (which, to be fair to Clinton, was a nigh-impossible task for a leading member of that regime), she built a new appeal on the foundations of the old neoliberal identity politics that technocratically reduced individual groups to disparate data points with zero-sum interests.

At New York magazine, Traister argued that Hillary Clinton “did not repeat her husband’s Sister Souljah strategy and instead emphasized themes of feminism and racial equality throughout her campaign.”

It’s true: Unlike in 2008, when she attacked Obama’s pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Clinton in 2016 highlighted the needs of women and people of color. But her new emphasis on marginalized groups — after years supporting welfare reform and the war on crime, and defining marriage as “a sacred bond between a man and a woman” — was still based on the same Clinton playbook, if with new talking points. For the most part, she took people of color for granted and figured their interests as narrow and symbolic, while ultimately failing to outline a big picture economic agenda that appealed to poor or working people of any race as such. Instead, she emphasized Trump’s dangerousness — a weak strategy given how many Americans have come to consider the status quo to be an existential threat.

During the Clinton era, it was the Left, battered and divided in the wake of Reagan, that unsuccessfully protested police brutality, mass incarceration, welfare decimation and corporate rule. During this year’s primary campaign, however, Hillary Clinton turned this historical debate on its head, suggesting that it was the Left that opposed the establishment’s embrace of racial justice: Sanders’ program for class struggle, she warned, not only failed to attend to racial, gender and queer justice but was also inherently hostile to them.

“If we broke up the big banks tomorrow, and I will if they deserve it…would that end racism?” Clinton asked at a Nevada rally. “No!” the crowd chorused. “Would that end sexism? Would that end discrimination against the LGBT community? Would that make people feel more welcoming to immigrants overnight?”As Matt Karp writes at Jacobin, Clinton staked her campaign on an “alliance between the Upper East Side and East Flatbush,” appealing not to working class people of any race but to a narrow sliver of moderate suburban Republicans who she incorrectly believed would be the swing vote turned off by Trump’s vulgarity. As former Pennsylvania governor and DNC Chair Ed Rendell put it, “For every one of those blue-collar Democrats he picks up, he will lose to Hillary two socially moderate Republicans and independents in suburban Cleveland, suburban Columbus, suburban Cincinnati, suburban Philadelphia, suburban Pittsburgh, places like that.”

That didn’t work out so well.

The Democratic Party elite, with an eye toward demographic trends, complacently believed that class politics were unnecessary because there were too few white workers and workers of color had nowhere else to turn. But demography is not destiny. People of color, hammered by economic crisis and mass incarceration, were stuck with voting Democratic or staying home — and many did the latter. Obviously, most black people won’t join a Republican Party that has become unapologetically white supremacist. But as weak black turnout — though complete data is not yet available, sharp declines have been reported in predominantly black Philadelphia, Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., New York City, and St. Louis neighborhoods — makes clear, the party cannot depend on black voters unless it changes the content of policy to address racial and economic injustice.

Obama now appears to be a charismatic interregnum in a party otherwise ruled by a sclerotic elite that lacks political vision and even the will to govern. Segments of the Democratic Party leadership don’t want to learn any lessons from Hillary Clinton’s loss save for some throwaway lines about needing to better hone their economic message. Obama, for one, put the blame not on economic policies but on messaging. It was, he told Rolling Stone, “a communications issue. … Whatever policy prescriptions that we’ve been proposing don’t reach, are not heard, by the folks in these communities.” Obama, of course, is selling his communication skills short: no one does it better. The problem is the politics that Democrats have been trying to sell. As Elizabeth Warren put it last November: “That’s where we failed, not in our messaging, but in our ideology.”

During the primary, Clintonites complained that Sanders’ strategy would sideline the interests of women and people of color. Now, some allies of Obama and Clinton (though by no means all) are intent on blocking a leadership bid from Rep. Keith Ellison, a black Muslim close to Sanders who seeks to refocus the party on economic justice to mobilize the working class of all races. The opposition stems from a heady centrist stew: on the one hand, discomfort with Ellison’s allegiance to Sanders-style class politics (the politics that supposedly sidelines identity politics) and on the other, uneasiness with putting a black Muslim a the party’s head.

The only path back to power is a coalition that represents a durable majority of Americans. That coalition cannot be led by the Clintonites whose immiserating and racist white identity politics facilitated Trump’s election. If the Left is to take the lead in the fight and, ultimately, prepare to take power, it needs to discard the long-running debate over identity politics. As we have shown, pitting race, gender and sexuality against class is misconceived and dangerously divisive.

A radical identity politics

Clintonian identity politics has provoked, understandably, a vigorous backlash on the left, leading some socialists to conclude that antiracist politics is the ideological handmaiden of neoliberal economic policies.

Proponents of neoliberal identity politics eschew an emphasis on class necessary to enact broad social and economic transformation for obvious reasons: such a transformation threatens the political-economic order they protect and represent. But anti-identitarian socialists suffer from a similar shortcoming, if for different reasons. By failing to engage existing collective identities or hoping to argue them out of existence, anti-identitarian socialists also fail to recognize politics and people as they are and thus how they can be mobilized for change. Racial or gender identity is not inherently hostile to unified class identity; ironically, however, the alienating political posture of anti-identitarian socialists may help to ensure that they are.

The pitfalls of equating identity politics with neoliberal identity politics were apparent at a November event in Boston, during which Bernie Sanders fell into the trap of knocking “identity politics” — thus unfortunately reinforcing its narrow meaning.

But what he substantively said wasn’t a criticism of identity politics full stop but of such politics in its neoliberal guise.

“It is not good enough for someone to say, ‘I’m a woman! Vote for me! … What we need is a woman who has the guts to stand up to Wall Street, to the insurance companies, to the drug companies.” He also said that having a black CEO was a good thing but not so great for black and Latino workers if they were exploiting their workers. From a standpoint of intersectionality this statement need not offend: If group interests are not monolithic but instead constituted by multiple sets of power relations, then knowing one vector of an individual’s identity (gender, or race) does not tell you much about who they are or what their interests might be. This fact should be uncontroversial on the left.

Pundits supportive of establishment Democrats were nevertheless aghast. One charged that Sanders wants “the left at-large to take up the mantle of the white working class — erasing in the process the unique marginalization faced by women and people of color, who more often live in poverty than their white and male counterparts.”

Radical identity politics do no such thing.

Marginalized and exploited groups form collective identities in response to shared conditions of domination — often in direct opposition to the identities imposed upon them by elites. To transform power relations, we must build solidarity between marginalized, exploited and excluded groups. That solidarity must be premised upon but not limited to common interests so as to preempt efforts to divide workers.

Despite the online rancor, there are countless examples of radical intersectional organizing: cross-fertilization between Black Lives Matter and Fight for $15 (as described in Sarah Jaffe’s recent book); the Movement for Black Lives platform, with its explicit emphasis on systemic racism and economic exploitation; hotel worker unionization efforts spearheaded by Latina women; or multi-racial and urban/rural coalitions to demand healthcare as a human right.

Building effective mass politics requires the articulation of forms of identity politics that are durable and conducive to solidarity. This does not mean that there are no tensions between the demands of distinct groups or between different strategies and tactics to advance those demands. Maintaining militant opposition to homophobia, anti-Muslim Christian supremacism, and police violence might not help win over white workers in the rural Midwest. But combined with a strong class program, socially conservative workers can not only stomach such positions but might even be convinced, over time, to change their minds. Difference, conceived intersectionally, highlights our common interests — and our real enemies.

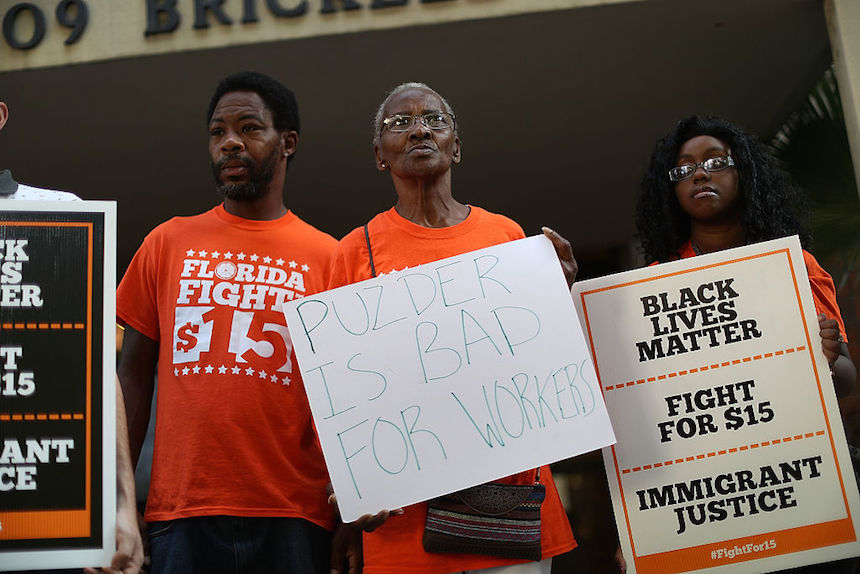

A protest against President Donald Trump’s pick for Labor Secretary, fast-food CEO Andy Puzder, outside the Miami Department of Labor on January 26 shows what radical identity politics can look like. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)