When Krista Looft first moved to the north-central Iowa town of Bancroft in 2012, she was a little concerned about starting a life here.

She moved with her husband Jaimes, whom she met in a Future Farmers of America scholarship program while each was attending different high schools. They hit it off on a trip to Washington, D.C.

They married young and lived in a tiny apartment in Emmetsburg while Krista studied to be an administrative professional and Jaimes a diesel mechanic at Iowa Lakes Community College. After graduating, Jaimes got a job at Deitering Brothers, one of two farm implement dealers in Bancroft.

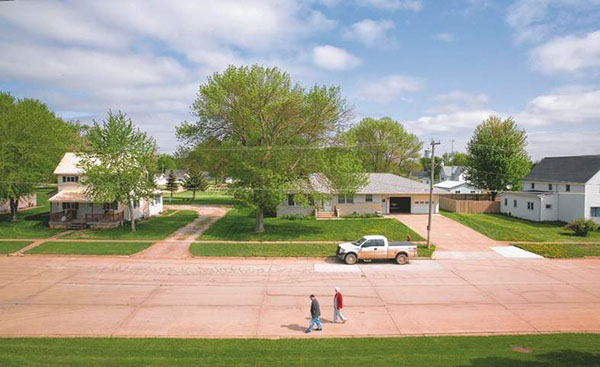

Bancroft is a small, and getting smaller, farming community most recently pegged at around 700 people. It’s one of the fastest shrinking of Iowa’s 942 cities. Located about 20 miles south of the Minnesota border on Highway 169, it is the second largest city in Kossuth County after county seat Algona.

Bancroft has no traffic lights and is about an hour from an interstate. The last local school — the parochial grade school, St. John’s — closed about five years ago. The high school closed in 1989.

Krista, who grew up 90 minutes away in Sioux Rapids, was just 19 when she arrived.

“I was worried at first there would be nothing to do,” says Looft, 25, who now has two boys, Jacob, 5, and Luke, 2. Her husband, Jaimes, is now 26. “That was the main concern.”

The farm crisis in the 1980s fueled the flight from rural Iowa communities such as Bancroft. Thanks to a decline in manufacturing, consolidation of farms and urbanization, the erosion of small-town populations has continued, and nothing suggests the trend will reverse. Those left behind — people like Krista and Jaimes — face the challenge of keeping the community going.

Conditions around the state are testament to the struggle — deteriorating housing stock, closed storefronts, communities disbanding, lack of participation and rising crime rates.

Those attributes are prevalent, but not all shrinking communities are ghost towns. Bancroft is a prime example.

“I think Bancroft is doing very good,” says Douglas Nyman, 66, who returned to town four years ago to care for his parents and remained after their deaths. He’s now president of the Bancroft Community Historical Museum. “It’s well run. We have a good City Council. We have a variety of things here.

“I am not worried about Bancroft.”

Locals point to smaller families, fewer people running larger farms, young people who leave for jobs or college and don’t return as reasons for population decline. But if you look around, you’d be hard pressed to say the community itself is in a decline.

Jobs and Real Estate

Homes are well maintained, and few if any are abandoned. The business strip — Ramsey Street — has just one vacancy and boasts a grocery store, two restaurants, a spa, the office of the Bancroft Registernewspaper, a medical clinic and a Ford dealership. A whiskey distillery is being built in a former dentist’s office.

The town has a golf course, municipal swimming pool, bowling alley, low-income housing options, an assisted-living facility, a library, the stately St. John the Baptist Catholic Church and a bed-and-breakfast called Sisters Inn — a nod to the fact it used to be a convent.

“This is a baseball town,” says John Nemmers, 73, who used to live across from the baseball stadium before moving to Algona.

He comes back to help with volunteer efforts, such as repainting the park this spring. Nemmers, a former ballplayer, identifies with the strong baseball roots in Bancroft, which produced two former major leaguers — “Lefty” Joe Hatten and Denis Menke — and several state championships.

Charlie Kennedy is a former mayor and president of Farmers & Traders Savings Bank. He left for school and work and returned to help run the family bank.

“When an out-of-town person comes into the community and says, how many people live here, when I tell them, they say, ‘Really? I thought you’d be a town of 1,500,’ ” Kennedy says. “We are not really a bedroom community. We are a self-contained community.”

His family moved here in 1898 to open Kennedy Bros. department store, which was a mainstay for more than 100 years. The space has been converted into the Main Street Pub & Grille, which serves as one of the town’s social centers.

Kennedy attributes the town’s success to a few things.

The public-owned electric utility helps subsidize the cost of city operations. The community as a whole has prioritized property upkeep, which helps maintain property values high enough that people are willing to keep investing. City government is well run, local leaders think big and a large number of citizens chip in money and sweat to local causes, he said.

Crysti Neuman, city clerk and director, is convinced if they had more houses, the population would grow. But it’s expensive to build, she said.

Like Many Small Towns

The numbers suggest challenges facing Bancroft are the same or worse than many small, rural towns far from a major city.

Bancroft has lost 32.35 percent of its population — 1,082 in 1980 to 732 in 2010 — since 1980, the largest decrease in the state for communities with at least 1,000 people in 1980, according to data from the most recent decennial census. That’s the smallest population since Bancroft incorporated in 1881 as a railway hub. The railroad depot was demolished in 1972.

In the past 20 years, only once were more babies born in Bancroft than people died — 11 births and 10 deaths in 2005 — and the median age increased from 41.7 in 2000 to 44.9 in 2010.

“We are a town of old people and widows,” says Linda Nemmers, 78, while taking a walk with her son, Tim Nemmers, 58, on Ramsey Street.

A fiscal year 2017 retail trade analysis from Iowa State University Department of Economics shows a mixed bag, with total taxable sales in Bancroft, sales per capita and the number of business entities declining slightly over the past five years, but wages and salaries per job increasing.

The Loofts are among 16 percent of the population over the age of 25 who have earned an associate degree; just six percent have a four-year degree, according to the economic development profile. Many who leave for a four-year school don’t come back, locals said.

“For some reason, you can find cities with identical demographics, population, economy, whatever, and one community is holding its own and maybe even growing, and the other is struggling,” says Alan Kemp, executive director of the Iowa League of Cities. “One community struggles to get someone to run for mayor or city council, and down the road there’s plenty running. That is the human capital, finding leaders in the community willing to take the lead.”

At some point, though, if Bancroft continues to shrink, it could face problems.

Kemp suggested a tipping point could come — perhaps when a community has a population of 100 to 300 — where it becomes difficult to maintain amenities and services. Of Iowa’s 942 communities, 360 have fewer than 300 people, and nearly 700 had lost population since 1980. Bancroft could be an example of a community “swimming upstream,” but vibrancy would become more challenging.

“Either you don’t have the financial resources to pay for the necessary upkeep or, on the human resources side, you have a hard time getting people to run for elected office,” Kemp said. “A slow reduction in population, and it becomes harder and harder for the city to survive.”

While more communities are discussing disbanding, it remains a rare event, one every year or two, he said.

Shrinking Smart

Challenges become cyclical, where population decline typically means a shrinking workforce, which makes a community less attractive to employers, declining support for local businesses and services and less energy for local causes.

“The myth is that there aren’t good jobs or, if there are jobs, they don’t pay very well,” Zachary Mannheimer, principal community planner for McClure Engineering Co. of Clive, who works with small towns to conceive development projects. “I would wager the majority of them have jobs. They just don’t have the people to take the jobs or keep the jobs.”

Mannheimer blames a lack of community leadership in some cases for woes, such as one county that was eager to bring in new employers but wouldn’t work with an employer planning to leave the community.

Iowa State University Associate Professor David Peters, who specializes in rural sociology, refers to “shrinking populations, exodus of younger people, job losses and poorer community services” found in most small communities in the Midwest, in a 2017 paper, “Shrink Smart Small Towns.”

That perception drives the focus of many scholars and journalists creating a “false premise that shrinking towns are also withering ones,” he wrote in his paper. “However, not all shrinking communities are withering. In fact, some small towns have thrived in terms of quality of life despite shrinking populations.”

Among other attributes, shrink smart towns are closely tied to agriculture and have managed to grow their industrial employment base, have high participation in local programs and civic organizations, are “better-kept, more open to new ideas, more trusting and viewed as safer places.”

Bancroft may be doing the best of the shrink smart communities, Peters said. Income and home values are lower, and poverty rates are higher than other shrink smart communities and other shrinking communities, according to his data.

Bancroft also scored comparatively low for education levels, employment participation and single-parent families.

The difference maker is local engagement, he says.

An ISU survey found 72 percent of respondents in Bancroft had participated in a community project in the past year compared to only 47 percent and 43 percent in other shrink smart communities and all shrinking communities, respectively. Bancroft also scored far better on community perceptions on safety, tolerance of different races and ethnicities, upkeep, and the sense Bancroft has “more going for it” than other communities, according to his data.

“They’ve played a really good hand with bad cards,” Peters says in an interview.

Here For Life

Neuman, the city clerk and director for the past five-and-a-half years, views the integration of younger residents into leadership roles as one of the biggest reasons for success. Younger participation is seen as a challenge in many smaller towns.

A “20s-30s-40s Meet With a Purpose” group has been an intentional effort to draw out ideas from younger residents and empower them, she said. Younger residents often need a direct invitation to participate, so her strategy has been to simply ask.

And it’s usually worked. At the baseball stadium, for example, younger volunteers will take charge of planning entertainment, music and social media, while older volunteers run concessions and tickets.

“People who’ve always led, we need to learn how to hand over those reins and make that a smooth transition,” Neuman says. “We are trying to figure out how to do that.”

On one Friday night in May in Bancroft, Ron Becker, 56, was working with his brother-in-law, Mark Schmidt, on an addition to his rental property.

Becker’s house is adjacent to the property, and his mother lives in the house next to his. The rental house, which has had just two different tenants in the 15 years he’s owned it, is for his mother-in-law. He’s building a new garage, entryway and bigger kitchen.

He is not concerned about recouping the investment — he is confident it will sell if he ever wanted to — but rather wants to have a say on who his neighbors are, he said.

“I am comfortable where I am, and I see no reason to leave,” says Becker, who’s lived in Bancroft his whole life.

Despite early reservations, Krista Looft settled in and also sees Bancroft as her family’s long-term home. She doesn’t mind the prospect of sending her boys out of town for school.

As with many people in town, she wears many hats.

She took a position last year as administrative assistant at City Hall, so she no longer has to commute to Algona to work. She runs a community Facebook page called Bancroft Minded, where she posts local activities and keeps people connected. Her kids go to Kidstop Daycare and Preschool, which is located in the old St. John’s school.

On Friday nights at Wrangling Grace restaurant, she and her husband often play games such as cribbage, rummy and pass the ace with friends their age during Game Night.

Last month, Krista worked alongside John Nemmers and about a dozen others on a Saturday morning to help repaint the green fence, dugouts and benches at Bancroft Park.

While mom painted, Jacob and Luke played with sand toys kept on hand at the stadium and ran around the infield.

The work has been going on several days this spring in preparation for the park’s 70th anniversary.

“We love the ballpark, and painting was a way we could show our support, put a little TLC into it,” she says.

(“Some Towns Continue to Shrink, But Many Iowans are Choosing to Stay” was originally published on The Gazette’s Iowa Ideas and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the editor. Iowa Ideas consists of in-depth, solutions-focused journalism and events. Engaged citizens, community advocates and industry leaders are invited to join them.)