A high-powered coalition of attorneys has filed a federal voting-rights lawsuit against San Juan County, Utah. They’ve done so on behalf of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission (NNHRC) and individual Navajo voters living in the county, which overlaps their reservation. The coalition includes The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, founded at the request of President Kennedy, the American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of Utah and international law firm DLA Piper.

The lawsuit alleges that San Juan County’s 2014 switch to mail-in elections makes it hard for non-English-speaking Navajos to vote because they can’t read the English-only ballet. Further, the change is predicated on the reservation’s unreliable postal system. If a voter doesn’t receive or understand a ballot, the option of casting one in person in the largely white northern part of the county — which has the only polling place left — is a difficult and costly trek for tribal members, who mostly live at great distances from it. These unequal burdens violate the Voting Rights Act and the Constitution, says the complaint, Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission v. San Juan County et al.

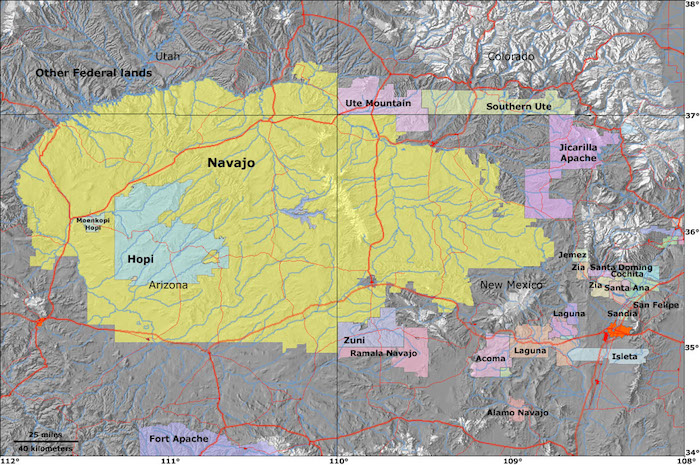

The Navajo Nation is the largest (27,000 square miles) and most populated reservation in the United States. San Juan County, Utah borders Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico at the four corners. (Image: usgs.gov)

“Protecting the right to vote has not resonated equally across the country,” says Leonard Gorman, executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission. “This causes our people to lose confidence in government. However, we at NNHRC are immersing ourselves in this issue and responding to each new challenge to our right to vote.”

For an in-depth look at San Juan County’s mail-in election problems, see the Rural America August 2015 story, Going Postal: How Mail-In Voting Thwarts Navajo Voters. According to Arusha Gordon, associate counsel for the Lawyers’ Committee’s Voting Rights Project, the article provided context for the attorneys and groups involved as they were crafting the lawsuit.

Where the ballot does, and doesn’t, get through

This is San Juan County’s fourth time at bat in a federal voting-rights matter. A federal judge recently found the county’s school-board and county-commission districts unconstitutional. In the 1980s, the county settled two lawsuits brought by the Department of Justice. One settlement required the county to replace at-large elections that had diluted the Navajo vote with single-member districts; in the other settlement, San Juan County agreed to provide federally mandated language assistance to those not proficient in English.

“The new lawsuit builds on decades of work,” says Gordon. “There is also more understanding nowadays that indigenous people’s voting rights are frequently left out of the conversation.”

Jurisdictions around the country have turned to the Post Office for their elections. Twenty-two states offer some mail-in options, and three states — Oregon, Washington and Colorado — use the mail for all elections, according to the National Council of State Legislatures (NCSL). The decision is typically made in hope that this will be more convenient for voters and might even save money, among other factors, says the council.

Whether postal elections are living up to their promise is not clear. They can increase election costs because of higher printing bills, says NCSL. They can also be unreliable. More than 20 percent of attempts to vote by mail fail, wrote political scientist Jean Schroedel in a 2014 research paper. This happens when ballots are lost on the way to voters or back to the election office and when missing signatures and other errors disqualify ballots, according to Schroedel. Mailing a ballot also appeals to better-off, better-educated voters, she found, which impacts ballot-box equality.

In 2014, the mail-in process seems to have worked well for San Juan County precincts in the mainly non-Native northern part of the county. County turnout records show these precincts had an overall lift in election participation when compared to the two prior non-presidential contests, 2006 and 2010. But then, mail delivery in these areas — county seat Monticello and nearby Blanding, Utah, among them — is similar to that of other U.S. towns and cities. And if voters wanted to cast a ballot in person, they could take an easy drive to the last remaining polling place, in the county seat.

[If you like what you are reading, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the wolf on the upper right of your screen.]

Not so on the reservation, in the southern part of the county. Cross the line and you are in a different world, of ancient culture, vast distances, great poverty, Navajo-language speakers — and a very different response to the mail-in election. When compared to the non-presidential elections in 2006 and 2010, some reservation precincts saw 2014 turnout drops as much as 20 percent.

Mail service here is also another world. To send and receive letters and packages, reservation residents rely on a patchwork of trading posts, contract post offices, regular post offices and commercial mail services, along with trucks shuttling mail among far-flung operations that may be a several-hour drive from any given tribal member’s home.

The Tonalea (Red Lake) Trading Post in the northern part of the reservation also serves as a post office. (Photo: jamesmcgillis.com)

Once a ballot is in this system, it travels to the reservation voter or back to the county via a sorting facility in Arizona, New Mexico or Utah, sometimes via multiple states. In researching reservation mail patterns, civil rights attorney Maya Kane, of the law firm Maynes, Bradford, Shipps and Sheftel, found that some 2014 ballots from Navajo precincts arrived at the county seat election office several months after the election.

Expert translation, please!

For tribal members who speak Navajo, but not English, the situation is very confusing. They may not realize that a particular piece of mail they’ve received is their ballot. “There was a lot of talk after the last election of ballots that went into the trash bin because Navajo-speaking voters didn’t know what they were,” says plaintiff and human-rights advocate Wilfred Jones, a resident of the reservation town of Montezuma Creek, Utah. “People from the county did come to chapter [Navajo Nation subdivision] meetings to explain the new system, but they spent a few minutes on it. It wasn’t enough.”

County officials have claimed that relatives can translate. Jones objects. Assuming the ballot didn’t end up in the garbage, it inevitably contains complex referendum terminology that doesn’t have ready equivalents in Navajo, according to Jones. It has to be translated by an expert, he says — specialists who used to be available at local precincts, as required by the Voting Rights Act.

On Election Day, if reservation voters realize they don’t have a ballot, or have one but can’t read it, they can drive to the county seat to vote in person. For plaintiff Terry Whitehat, a hospital administrator and resident of the reservation town of Navajo Mountain, Utah, the journey would be about 400 miles round trip across the parched desert and rugged mountains of the Monument Valley region.

Whitehat explains what such an undertaking means in this forbidding land. “I stock up on food and water. I make sure my vehicle is in good condition and tuned up. I check the water, oil and tire pressures. I gas up and make sure I have money for the return trip.” Many of his neighbors are impoverished and don’t have access to a reliable vehicle and the cash for fuel; for them, the trek is out of the question.

County commission chair Phil Lyman has told Rural America that the 2014 election was a “test case” and that “we aren’t wedded to vote by mail.” By publication time he had not responded to Rural America regarding the latest lawsuit. However, Lyman has told Utah Public Radio that the case was “spurious” and the result of a vendetta by former commissioners. About the county’s recent voting-rights losses in federal court, he said to UPR, “The appalling thing to me is that you’ve got a federal judge who entertains this crap. And I don’t know what San Juan County’s response is, other than, you know, filing lawsuits ourselves.”

“Don’t penalize me because of who I am and where I live,” says Jones. “The government put us on this reservation, and now we can’t vote because we live here. We Navajos have a right to vote. This is the twenty-first century. Why has this taken so long?”

Stephanie Woodard is an award-winning human-rights reporter and author of American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle for Self-Determination and Inclusion.