Native Americans naturally greet any U.S. federal legislation that involves their culture with skepticism. The National Bison Legacy Act (NBLA) is no exception. Despite its support from tribal governments, communities and their allies, the bill granting the bison “national mammal” status remains problematic.

The NBLA, adopted by Congress with unanimous consent this past April, follows in the footsteps of the establishment of National Bison Day, which passed in Fall 2015 and designates the first Saturday of November as the annual day of celebration.

Bison deserve both honors. They can run up to 35 mph and, whether commercially, privately or publicly owned, are found in every U.S. state. For centuries, Native Americans have culturally respected and coveted the animal. (Note that North American bison, with their small sharp horns and large hump, are still often confused with buffalo, who have long horns and no hump. This misclassification is believed to originate with Europeans who noted their resemblance to Asian and African buffalo.)

An initial concern with any federal action integrating Native American issues is invisibility. In particular, the federal government chronically fails to include Native voices or perspectives. This particular piece of legislation attempts to interrupt that trend. The cultural significance of bison to Native nations is mentioned a handful of times throughout the NBLA, which cites Native advocacy as a reason for the legislation. The Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), made up of 62 tribes from 19 states, is also acknowledged in the text.

![]()

Chief Earl Old Person of the Blackfeet Nation. He retired in 2008 after 54 years as a tribal official, 34 of them as tribal chairman.(Photo: indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com)

The ITBC is part of the Vote Bison Coalition that began championing the national mammal designation over four years ago. Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper (D), Blackfeet Nation Chief Earl Old Person and Ted Roosevelt V head the 63-member coalition’s advisory council. Recognition of this Native support is an example of the federal government heeding the voices of their Native neighbors and citizens.

That said, unlike “The Buffalo: A Treaty of Cooperation, Renewal and Restoration” — a 2014 treaty signed by Native peoples on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border that aimed to restore the buffalo’s place in the lives of all Indigenous Peoples of North America — the NBLA lacks an emphasis on conservation and education.

A history of legislation but no real action

According to Defenders of Wildlife, “an estimated 20 to 30 million bison once dominated the North American landscape from the Appalachians to the Rockies, from the Gulf Coast to Alaska.” Today, approximately 500,000 bison live across North America however most are not “pure wild bison” but rather semi-domesticated populations following generations of cross-breeding with cattle. Of the fewer than 30,000 wild bison roaming the continent, the organization estimates that “fewer than 5,000 are unfenced and disease-free.”

Though the legislation mentions in passing the near extinction of the bison at the hands of colonial settlers, the National Bison Legacy Act fails to enhance protections or management protocol for bison. It instead notes that “a small group of ranchers helped save bison from extinction in the late 1800s by gathering the remnants of the decimated herds.”

Unidentified man sitting on top a mound of bison hides. (Photo: democraticunderground.com)

The decimation of the bison occurred during the Plains Indian Wars as a part of a deliberate U.S. military strategy. In 1867, U.S. Colonel Richard Dodge made this sentiment clear when he said, “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” The formation of the American Bison Society in 1905 sought to reverse the damage. The group’s first major feat came in 1907 when they relocated (by train) 15 bison from the now Bronx Zoo to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. These efforts were led by President Theodore Roosevelt and William Hornaday, the first president of the Wildlife Conservation Society. Hornaday, ironically, was the same man who, in 1889 as the superintendent of the National Zoological Park, blamed the “phenomenal stupidity of the [buffalos] themselves, and their indifference to man” as a secondary cause to their near extermination. The society called it quits in 1935 when its members felt the bison were saved after herds were reestablished in Yellowstone National Park. Seventy years later, the American Bison Society was reestablished in 2005 to reevaluate the future of bison in North America.

Further federal action picked up when the National Bison Legacy Act was first introduced in 2012 by Rep. William Lacy Clay (D-Mo.) and again in each successive year. The act was finally passed in both houses in identical form on April 28, 2016.

Upon Obama’s enactment on May 9, 2016, Clay exclaimed, “The American bison is an enduring symbol of strength, Native American culture and the boundless western wildness. It is an integral part of the still largely untold story of Native Americans and their historic contributions to our national identity.” Sen. Martin Heinrich [(N.M.) boasted that the bison was the “embodiment of American strength and resilience” while Rep. Jeff Fortenberry (R.-Neb.) praised the bison as “an important part of our nation’s frontier heritage.”

The “frontier” that Fortenberry mentioned is the Great Plains where bison roamed for centuries before being decimated by the “pioneers” and the U.S. military. But even with the stamp of American symbolism, the act fails to address the actual modern treatment of this essential wildlife. The legislation reads:

“Nothing in the Act or the adoption of the North American bison as the national mammal of the United States shall be construed or used as a reason to alter, change, modify, or otherwise affect any plan, policy, management decision, regulation, or other action by the Federal Government.”

Meanwhile, the managerial practice of culling — the annual slaughter of Yellowstone bison — dating back to the 1980s will remain intact. In other words, the honorific status does not bring privileges. In the wake of the systematic killing of bison it seems a greater gesture of protection should be made with the congressional coronation of the resilient bison, such as allowing Native nations to manage the protection and cultivation of bison herds.

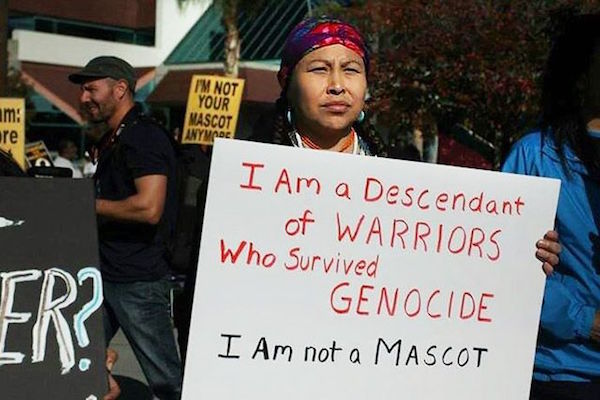

The mascot issue

Given highly publicized opposition to Native appropriation in the marketing of sport teams, a striking problem with the National Bison Legacy Act is Section 2 (21): “several sports teams have the bison as a mascot, which highlights the iconic significance of bison in the United States.”

The mascot issue in Indian Country and the United Sates is tense to say the least. The legal battle with the Washington NFL football team and its racist iconography highlights the conflict found with other major league sport teams in Cleveland (Indians), Kansas City (Chiefs) and Chicago (Blackhawks), in addition to the countless high schools across the nation.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association (APA) published a resolution revealing the damaging effects of American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities. The use of these by teams, organizations and schools teach non-Native children with minimal, if any, contact with Native peoples, to engage in culturally abusive behavior and maintain false conceptions of Native culture. Furthermore, the people most effected by the presence of American Indian sports mascots are Native youth. The APA American Indian Mascot Resolution called for an immediate retirement of all Native American mascots.

Woman holding sign outside a California football stadium during 2014 Native American mascot protest. (Photo: Twitter)

American culture directly associates bison with Native Americans. Since first contact, the mammal has come to symbolize Native culture in the eyes of non-Natives across the country. Bison mascots fall into the category of unacceptable symbols described by the APA resolution.

The Act’s supporting reasoning for national mammal status, in that it endorses the use of Native mascots, actually harms Natives when it is meant to empower them. In the midst of the heated mascot climate and the harmful effects caused by Native Americans mascots and symbols, the use of bison sport mascots as an indication of its significance in the United States demonstrates an ignorance of the struggles Natives face today.

May 9 marked the passing of the National Bison Legacy Act. On the same day in Yellowstone National Park, a bison calf was “rescued” by tourists. The act of good faith ended in the rejection of the calf by its herd. Shortly after, the calf was euthanized.

Misinformed acts of good faith can end tragically. Time will tell if this one does.