How the Hydroponics Industry Is Undermining Everything the Organic Farming Movement Stands For

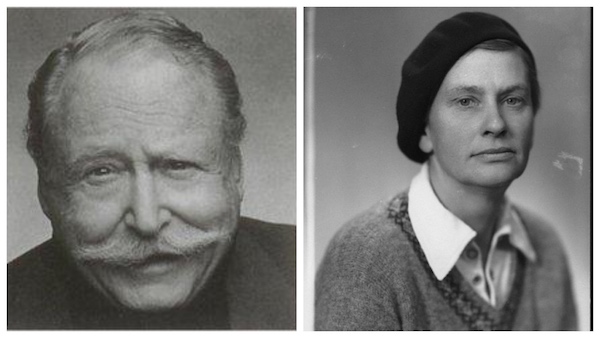

Dan Bensonoff

Editor’s note: In the 1990s, when the Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) was drafting what it would mean to be “certified organic,” they defined organic agriculture, in part, as “an ecological production management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity.” In other words, USDA set legal standards for a system of food production that, unlike the ecologically destructive, tremendously profitable industrial model, focused on the long-term health of the land (i.e. soil) and water on which hard-working farmers cultivate food. In theory, at least, the USDA’s “organic seal” would allow consumers to identify the goods produced by those farmers willing to put in the extra work — forgo the use of synthetic inputs, steer clear of genetic engineering, implement crop and grazing rotations etc. — and focus on sustainable growing practices.

Recently, however, hydroponic produce — fruits and vegetables grown in a controlled environment, in nutrient baths and without soil — has been dominating the industry. And the question as to whether or not soilless hydroponics should be “certified organic” has been the subject of fierce debate among organic farmers, food corporations and consumers. Last November at its meeting in Jacksonville, Fla., the NOSB, responding favorably to a massive lobbying effort on the part of industrial agribusiness, voted 8-to-7 to reject an attempt by the sustainable farming movement to prevent hydroponic produce from being certified organic. Many organic farmers insist that the decision is not only wrong but “illegal” under the Organic Food Production Act (OFPA). Below is an interview that explains why this issue is so important to those putting everything on the line to grow food responsibly.

Since 1984, Dave Chapman has been growing organic tomatoes at his Vermont-based Long Wind Farm. Until recently, he was content to keep his nose to the grind stone. But then, a few years ago, he started to notice something different about the organic tomatoes at all the grocery stores he visited: They were almost all hydroponically grown, and almost all were coming from just a few large companies.

Surely, he thought, this must be an oversight, since hydroponics had been banned since 2010. He started petitioning, digging and talking to figure out what this was all about. The hornet’s nest that he’s since dug up has become one of the most controversial issues in the organic industry. With deep integrity, Dave has been leading the charge to “keep the soil in organic” through rallies, presentations and public education.

I caught up with him at the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) Summer Conference to ask him why this issue is such a threat, and why it has become his cause célèbre.

Why do you think that hydroponics is the primary threat to the organic program?

I would say it’s one of the primary threats, and it happens to be the one up on deck right now. Five years ago, I thought the organic system was working pretty well. I had no issue with the standards. The inspectors from Vermont Organic Farmers who I work with are awesome. They have total integrity. No monkey business. As far as I knew, I thought the standards were good.

I’m not a political guy. I never went to any meetings. I just farmed, worked hard, raised two kids. That was my focus. And then a few years ago I started to see all these organic hydroponically grown tomatoes in the supermarket. Most of them were coming from a place called Wholesome Harvest down in Mexico. I knew just enough about the organic policy to know that they had recommended a stop to hydro in 2010. And so, I thought it was an oversight of the USDA’s National Organic Program. I started some petitions, thinking that, surely, if we point this out, it’ll get fixed. But no, it was not an oversight.

The truth is, if we don’t stop this, in five years virtually all supermarket certified organic tomatoes, peppers, and cucumbers will be hydroponic. That’s what organic will mean to most organic eaters, is hydro-grown stuff from massive greenhouse complexes… Is that what organic means to us? I don’t think it is. It’s not what it means to me, and I’ve barely met anybody in the organic community who says, “Yes, that’s what organic means.”

Nobody believes those places should be organic except the people that run them. And yet they are. Even when they are clearly breaking the law, they still remain certified. And it’s not just the hydroponic growers. As I got into this, I realized there are serious problems. I didn’t know there were organic CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). Just recently, we saw that searing article from the Washington Post confirming the Cornucopia Institute’s allegations. Those hen houses that have porches are breaking the letter of the law. In fact, I discovered that the first case on that was in Massachusetts. NOFA[Northeast Organic Farming Association]/MASS [Massachusetts] had refused to certify The Country Hen over their use of porches. The Country Hen took it to court and the decision was overturned. And that’s how we got porches.

One of the key points that opponents of organic hydroponic often cite is the extensive use of inputs in hydroponic systems for fertility. But most of the organic farms that I’ve worked on also rely on purchased fertility to some degree. What is different about the use of inputs in hydroponic systems that should disqualify them from an organic seal?

Eliot Coleman, the American farmer and author, talks about “deep organic” vs. “shallow organic.” The idea of deep organic goes back to the days of Sir Albert Howard and Eve Balfour. Organic farming, or as they sometimes called it, “humus farming,” is all about tending to the organic matter in the soil so that you’re tending to the life in the soil. They didn’t know the scientific basis of their work, but they anecdotally noticed that farmers who use compost and green manures end up with more nutritious foods, and thus, healthier people. That was the foundation of organic farming.

So I think that initial vision of organic farming is what Stuart Hill (another long-time organic pioneer) and Eliot Coleman would call deep organic. And at the other extreme, the most shallow organic, are those that say “instead of using this bagged synthetic fertilizer, I’m going to use this bagged natural fertilizer.” Except their fertilizers aren’t so natural. They’ve been processed; it’s just that instead of a chemical process they’ve been hydrolyzed through enzymatic processing. You can find a hydrolyzed soy protein fertilizer that’s 18−0−0 (nitrogen-to-phosphorus-to-potassium ratio). That’s hot! That’ll burn the roots right off the plant. It’s very soluble, very available.

We’ve gotten better and better at gaming the system. There’s nothing cosmologically wrong with hydrolyzed soy protein, it’s just that when you start to rely on bagged Nitrogen, it becomes an addiction.

But wouldn’t you say that most organic growers do also rely on bagged fertility?

Well, I don’t know. I know my little circle of friends and I do not. And I would say that if they do they’ve wandered pretty far from the meaning of organic farming.

I was really fortunate because when I started farming I lived right down the road from Eliot Coleman. We were good friends and he was like a tutor for me. We did all sorts of potting soil experiments together, and he lent me book after book. So I got a really fine education in this.

The thing about conventional ag is, it works. If you put those fertilizers on you can get a really green, lush, productive crop. The problem is, if you’re ignoring the organic matter in the soil, you starve the soil biology and insect and disease problems become greater and greater.

There’s an innate intelligence in the relationship between plants and the mycorrhizal fungi because they have co-evolved together. They want the same thing. We know of 33 different nutrients that plants need to survive. Getting those balances right is the genius of a healthy soil system. If you’re applying those nutrients from a bag, the chances of getting those ratios right are very slim. That’s why we believe a deep organic system produces health. It has an inherent wisdom built into it.

How much does the technology of hydroponics influence the market share of these large operations? In other words, wouldn’t they still dominate the market if they were producing soil-grown organic products?

I have an inherent distrust of large financial enterprises. Not because they’re big, but because they tend to be completely driven by profit motive. I want to make a living too. But the problem with Driscoll’s is that they want to change the rules to fit how they grow. They don’t want to change the way they grow to fit the rules. If Driscoll’s said, “we’re going to completely dominate organic farming but we’re going to have real organic. We’re going to do it right and we’re going to have spectacular quality.” I would say, “Ok, you’re going to be tough to compete with, but God bless you.” That’s changing the system, that’s what we wanted to do in the first place: change how the world farms.

Some of my good friends in the world are large-scale hydroponic growers: conventional, not organic. I don’t agree with the way they farm, but we’re friends. I’ve learned a lot from them. It’s getting to the point now where any large-scale hydroponic vegetable operation has to look into getting certified organic because the market pressure is so great. The profit potential is so great for going in that direction that they will. Thousands of acres of greenhouse production are going to be producing this way, and that’s going to drive the price of organic vegetables down substantially.

Is there any research that demonstrates any nutritional differences between hydroponic and soil-grown produce?

I don’t know. There have been a bunch of tests, but they always disagree with each other or are inconclusive. It depends what they’re testing for. In terms of major nutrients, hydroponic probably wins because they’re fed as much fertilizer as they can handle. But the food is of a lower quality, especially if you look at the microbiome. Some, like my friend who studies both aquaponics and organic systems, also believes that there’s a difference in energy level. Food used to be called spirit, or soul. There are things there that are different. Just as an example, we can look at ergothioneine, a nutrient that comes from fungi. If you eat mushrooms or food from healthy soils you tend to get it. We now know that it’s an anti-carcinogen.

Hydroponics wouldn’t have any because it doesn’t have soil. We don’t know everything that comes from the soil. It’s incredibly complex. It’s beyond our ability to understand right now.

The thing that’s neat about the organic system is that it’s based on nearly 400,000,000 years of coevolution between soil and plants. That’s a long time. Our ancestors evolved by tapping into that system. And then about 100 years ago, we said “the hell with it. We’re smarter than that.” And we did come up with some amazing stuff. But it’s like speed. It feels good the first day, but then after two weeks you start to feel pretty bad.

(“Hooked on Hydroponics, Dave Chapman on the Shallowing of Organics” was first published in the Northeast Organic Farming Association of Massachusetts’ (NOFA/MASS) September 2017 newsletter and is “the first in a series of interviews with organic heroes from across the Northeast.” It’s reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission from the organization and author.)