When I entered the Office of Pesticide Programs of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1979, I knew practically nothing about pesticides. Though I had taken classes in chemistry in college and had even written my first book about industrialized agriculture, nothing prepared me for the secrets I uncovered during 25 years of work in a bureaucracy designed and brought up to keep secrets.

My colleagues opened my eyes to the secret world of chemical sprays deceptively known as pesticides. They kept answering my questions and, more than that, they started giving me their memos, briefings and scientific papers. They did not see much controversy in the “regulation” of pesticides. Most thought pesticides were necessary for farming.

In fact, EPA economists always defended pesticides, suggesting that without them food prices would go through the roof. Other EPA scientists like biologists, ecologists, chemists and toxicologists monitored those chemicals for ecological and health effects. They had read the pesticide law — The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act — and, some of them, were authors of regulations for their use on farms, lawns, homes, factories and the natural world.

Who was going to object to the killing of “pests” like insects, rodents, fungi, and weeds?

It did not take me long to object to the use of pesticides, however. My knowledge about these chemicals increased rapidly. The writings of my colleagues and the discussions I had with them convinced me pesticides were more than pesticides. They are petrochemical biocides. They kill everything.

But there was something particularly insidious about certain farm sprays that were born about a century ago in the heat of WWI. The organophosphates parathion and malathion, for instance, are nerve gases related to chemical weapons. They are chemical weapons in diluted form.

I remember how EPA ecologists reacted to the news that parathion was killing honeybees in droves. They were very upset and urged senior officials to prohibit any more approvals of the deleterious nerve gas. The senior officials did no such thing. Honeybees continued to die from parathion poisoning for decades. EPA banned ethyl parathion in 2003. In 2015, the White House Energy-Climate Czarina and former EPA administrator, Carol Browner, announced the banning of methyl parathion on “all fruits and many vegetables.” Now, in 2018, honeybees die primarily from another version of neurotoxins, known as neonicotinoids, manufactured in Germany.

Yet I don’t remember hearing EPA scientists connecting parathion and other neurotoxic pesticides to warfare agents. I found that strange because one heard of the horrible consequences they had in common: pinpoint pupils, sweating, convulsions, vomiting, asphyxiation and death. But the military connection of many pesticides made their origins obscure and very difficult to decode. It was as if there existed a universal pact among experts in industry, academia and government not to question these extremely toxic compounds.

If Americans knew their food is contaminated by neurotoxic agents, what would they say and do? And how would the environmental movement act on the evidence of nerve poisons in conventional food?

According to Anna Feigenbaum, Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, modern tear gas also operates in the same mist of ignorance and fear that surrounds neurotoxic pesticides. Tear gas is not a gas at all. By tear gas we mean groups of chemicals, which are lachrymatory agents. This in Latin means they cause tears. Popular tear gases include CS (2-chlorobenzylidene malonitrile), CN (chroroacetophenone) and CR (dibenzoxazepine) — irritants released as smoke, vapor or liquid sprays. Another tear gas is pepper spray or OC (oleoresin capsicum). This is an inflammatory substance triggering tears.

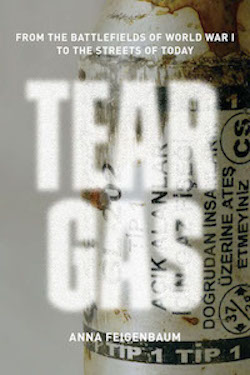

Feigenbaum chronicles the history of tear gas intelligently and with passion in her new book, Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of World War I to the Streets of Today (Verso, 2017).

According to Feigenbaum, tear gas started its warfare career in August 1914 when French troops fired grenades filled with methylbenzyl bromide into German trenches. The effect was to break the stalemate of trench warfare. Tear gas forced the German soldiers to run out of their protective trenches, only to be mowed down by French machine guns. This was the Battle of the Frontiers. In April 1915, at Ypres, the Germans retaliated with chlorine gas. The war of asphyxiating gases was in full swing.

Daan Boens, Belgian soldier-poet lived through this nerve gas war. In 1918, he published a poem, “Gas,” in which he caught the barbarism of chemical warfare. Feigenbaum cites the poem:

The stench is unbearable, while death mocks back.

The masks around the cheeks cut the look of bestial snouts,

The masks with wild eyes, crazy or absurd,

Their bodies drift on until they stumble upon steel.

The men know nothing, they breathe in fear.

Their hands clench on weapons like a buoy for the drowning,

They do not see the enemy, who, also masked, loom forth,

And storm them, hidden in the rings of gas.

Thus in the dirty mist, the biggest murder happens.

Like the pesticide merchants and lobbyists, tear gas advocates have buried this murder. They, according to Feigenbaum, reject the effects of their product: tearing, gagging, miscarriages, burning of the eyes, blindness and death. They paint the military origins and use of tear gases into oblivion. The result of this successful propaganda is that tear gas faces none of the prohibitions against chemical warfare agents. A straightforward war gas — tear gas — has become a peacemaker. Innocent of harm.

Feigenbaum laments in particular the difficulties she faced in tracking sales and use of tear gas. She writes:

There are just too many secrets and too many lies. The international trade in tear gas is buried under bureaucracy and often classified beyond the reach of Freedom of Information requests. There are files upon files that have been shredded and burned, deleted, altered and falsified.

That’s to be expected of a chemical warfare agent dressed in civilian clothes.

Yet Feigenbaum eventually succeeded in her task. Her book is a lucid history that puts tear gas on trial. She exposed the profiteers, scientists, military buyers, arms dealers, police suppliers and editors trying to put a humane face on a dangerous weapon.

Neurotoxic pesticides are connected to tear gas by neurotoxicity. They are also products of chemical warfare. They kill by nerve poisoning and asphyxiation. They should be banned.

As Feigenbaum sees it, in its civilian life, tear gas does more than killing. It is designed “to torment people, to break their spirits, to cause physical and psychological damage.”

Read Feigenbaum’s book. It’s timely, well-written, and very important.

(This review was first published by Independent Science News and is reposted on Rural America In These Times with permission.)