Humans must work hard to create economies that enable them to thrive.

Imagine, then, the discovery of a nutritious food source whose propagation requires little human intervention to make it grow generation after generation: no tilling, planting, irrigation or pest control.

Now imagine that food source threatened by a transient economy; an economy bound to place by a singular resource that upon exhaustion signals an exit.

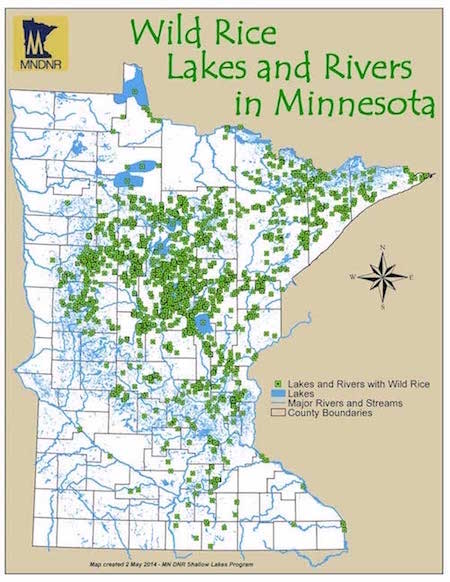

The food source in question is wild rice—manoomin in Ojibwe — and it’s one of a few grains indigenous to North America. Wild rice grows in lakes and rivers and, in the United States, it’s found in abundance in Minnesota, the “Land of 10,000 Lakes.”

Robert DesJarlait, co-founder of Protect Our Manoomin, a group working to protect Minnesota’s wild-rice economy, says wild rice faces two existential threats: “Mining and Enbridge’s pipelines.”

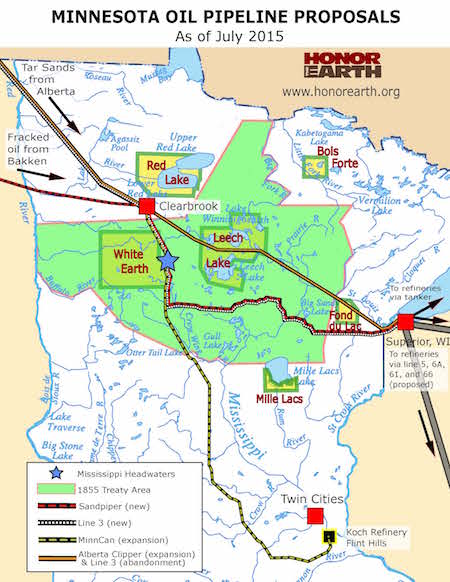

The pipelines “run through the middle of Minnesota, across the wild-rice lakes and tribal areas.” He worries about pipelines carrying an ultra-heavy crude called bitumen, but so far there have been no Kalamazoo, Michigan-sized spills.

(Source: MN Department of Natural Resources)

Mining occurs mainly in the northeastern part of the state, known as the Iron Range, or Range for short. Those mines pose a threat to the rice, says DesJarlait, because “sulfate from the mining gets in the water, floats down stream and embeds in the sediment.”

PolyMet’s ‘$1 trillion mining jackpot’

The biggest mining proposal in the works, and at the heart of a heated debate, is PolyMet Mining Corporation’s NorthMet Project, a copper-nickel mega-mine near Minnesota’s Iron Range. The proposal for an open pit mine, processing plant and tailings basin cleared a significant hurdle in March when the state signed off on a 3,500-page environmental review that clears the way for PolyMet, a Canadian mining company based in Toronto, to obtain other approvals and permits needed to begin the construction phase.

In the interim, groups like Protect Our Manoomin, based in northern Minnesota, are working at the legislative level to ensure that all of the state’s natural resources are protected equally.

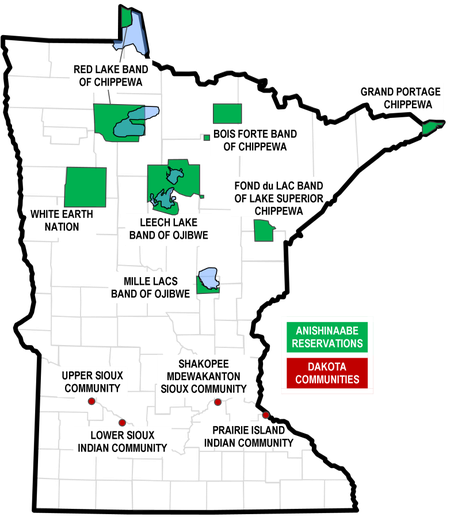

DesJarlait, a member of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, concedes that jobs in northeastern Minnesota are needed, but he says mineral extraction provides short-term gains and leaves behind long-term environmental damage. He is not sure a few hundred mining jobs now will be considered worth it by future generations who must live with the resulting pollution.

‘Sulfide kills seedlings’

Minnesota is rich in lakes and self-propagating rice. It’s also rich in ferrous and non-ferrous metals: taconite and iron ore; copper, nickel, manganese, titanium. But mining for those metals also unleashes sulfate, a naturally occurring chemical known to negatively affect the growth of wild rice.

According to John Pastor, professor of ecosystems ecology at the University of Minnesota Duluth, “waters in the mine pits can have very high sulfate concentrations.” Those waters leach into streams and groundwater and then into wild-rice lakes. The sulfate itself isn’t toxic, he says in an email. It’s when sulfate is converted to sulfide by microbes in the sediments of the lakes that toxicity occurs. “It’s the sulfide that is toxic. Sulfide kills [wild rice] seedlings.”

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA), which is revising its 1973 water quality standards, is currently deliberating the amount of sulfate-converted-to-sulfide necessary to kill or thwart wild rice growth.

The 1973 standard limits sulfate pollution to 10 milligrams per liter in waters used for the production of wild rice. That means Minnesota’s big sulfate emitters — municipal wastewater treatment plants, industrial facilities and mining operations — aren’t allowed to discharge water with sulfate levels that exceed that limit, at least in theory.

But that standard, says Iron Range state Rep. Carly Melin (DFL), “was never in a permit and never enforced. It only came to the MPCA’s attention in 2010, from these groups who were trying to stop PolyMet mining.” Melin is correct, but to put a finer point on it, it’s the mining sector that has escaped scrutiny until recently.

For the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce and some state legislators, the 10 mg/L sulfate limit is a contentious issue. Mining permits have lapsed and new ones are needed. They fear that MPCA could, at the urging of “these groups,” begin enforcing the 1973 standard that limits sulfate pollution and that could hit mining operations hard.

But that’s not likely to happen: A bloc of lawmakers who represent the state’s Arrowhead Region, a northern area where most mining occurs, strategically added a section to Minnesota law in 2015 that has stopped exercise of the 1973 standard all together. As reported by the MinnPost, a non-profit news outlet, MPCA Commissioner John Linc Stine “has set the agency’s permit work aside in order to concentrate the staff’s efforts on developing a standard for sulfate in wild-rice waters.”

Suspension of the standard is good news for mining; it means the MPCA won’t use it as a condition for permitting. Even if it did, the 2015 legislative change restricts the agency from requiring permittees to spend money on measures to control or mitigate sulfate pollution. It’s hard to say when Stine’s staff might finish developing a “refined” standard by way of new criteria for protecting wild-rice waters, or when those changes might be adopted through state rulemaking (though lawmakers have set a deadline of January 15, 2018). What is certain in the foreseeable future is that new mining permits won’t include a sulfate limit. Expired permits won’t undergo scrutiny for sulfate pollution either. Mainly because the law change in 2015 stipulates that a numeric limit for sulfate pollution “can be added” to permits after the MPCA commissioner amends the rules. That is, when the numeric limit is not the current standard of 10 mg/L.

EPA intervention

Federal regulators might think otherwise, the water quality standard isn’t entirely under state control. WaterLegacy, a non-profit group working to protect Minnesota’s water resources, filed a petition in summer 2015 with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) requesting it “strip the state of authority to regulate mining pollution under the Clean Water Act.” Legal grounds cited by the group in its petition include the 2015 legislative change that interferes with “MPCA’s compliance with the Clean Water Act to control sulfate pollution in wild-rice waters.”

The EPA has taken notice. The agency launched an investigation soon after receiving the petition. (Communications with state authorities can be found here, along with WaterLegacy’s supporting documents.)

“Minnesota is beautiful everywhere you look,” says DesJarlait. The state has crafted some good laws to protect the environment. But he says that what is happening politically with those laws are “creating the conditions for ecocide.” It’s a strong word, but he says multinational corporations like PolyMet are not in it for the long run.

DesJarlait wants the 1973 standard enforced. He says the state should be in the business of safeguarding natural resources, especially when good ecology is required to support smaller economies such as rice harvesting and tourism.

For Native families in Minnesota, the wild rice is part of a small, indigenous economy and a yearly harvest can provide a couple of hundred pounds of rice for each household. “They can sell some of it,” he says, “but they don’t get rich. Maybe they’ll be able to buy books for their kids, or new tires for the truck. But it does provide for the families, and it’s easy to store indefinitely.”

The wild rice is also nourishing in other ways. Its constant stewardship and annual harvest are ceremonial and communal activities that provide identity and a sense of continuity.

On some level, lawmakers agree. Wild rice was adopted as the state grain in 1977. It stands as one of 17 symbols adopted by the legislature to “identify the state’s great resources and quality of life.”

‘Keystone XL of the Great Lakes’

DesJarlait’s group, Protect Our Manoomin, deals mainly with the sulfate threat and mining expansion. Another group, Honor The Earth, tackles pipelines and other energy issues.

According to Winona LaDuke, Honor The Earth’s executive director, “While the national press has kept a focus on the controversy over the Keystone XL pipeline, something is going on in northern Minnesota.” That something, she says, is Enbridge’s massive pipeline program that is “far more than a single Keystone pipeline.”

The Keystone XL pipeline (had it not been defeated) would have added 830,000 barrels per day to TransCanada’s “base Keystone” system. By comparison, Enbridge Energy is moving almost three million barrels across Minnesota each day. The system of seven lines transports both heavy crude and bitumen from Canada, with routes traversing tribal areas, lakes and the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

(Source: honorearth.org)

If all goes as planned, Enbridge will continue to add capacity for Canadian product as well as build a new line, called the Sandpiper, for transporting Bakken oil from North Dakota.

LaDuke is not against infrastructure projects; it’s a trust issue. She told City Pages reporter Mike Mullen that people don’t trust Enbridge, and shouldn’t.

The costliest onshore spill in U.S. history was the result of a pipeline rupture on Enbridge’s Line 6B that fouled Michigan’s Kalamazoo River. The oil that spilled, it turned out, was not ordinary crude. It was diluted bitumen; an ultra-heavy crude that must be diluted with lighter hydrocarbons to make it flow through pipe from the Alberta oil sands. It would take Calgary-based Enbridge more than 17 hours after the pipeline burst to shut down the line, and it would be a week before on-site testing proved it wasn’t conventional oil.

The EPA, if it could have its way, would require pipeline operators who run dilbit — Enbridge, Exxon, TransCanada – to have oil spill response plans specific to bitumen. While the EPA is often the lead agency in catastrophic cleanups, it doesn’t make upfront rules when oil is in transit. That’s the job of the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA).

In the present, PHMSA doesn’t require disclosure of diluted bitumen in pipelines and, by extension, doesn’t require operators to prepare oil spill response plans for dilbit (just ones for “petroleum crude oil”). PHMSA also doesn’t require Safety Data Sheets (SDS) from operators, an omission that has resulted in critical delays at the onset of spills.

An SDS is a complete document that provides detailed information on the chemical constituents of a hazardous material as well as appropriate safety precautions. Suppliers are required to provide those sheets along the supply chain to comply with workplace safety laws in both the United States and Canada. In the United States, however, Safety Data Sheets for dilbit aren’t readily available and when they are, “petroleum crude oil” is often substituted for bitumen as the main ingredient.

Paul Blackburn, attorney for the Minnesota chapter of the Sierra Club, says he’s “not aware of any way that citizens can learn the contents of a particular pipeline or train in real time,” though determinations can be made by knowing the “oil fields served and refinery destination.”

An online database, called the National Pipeline Mapping System, maintained by PHMSA, allows the public to locate oil and gas pipelines in the U.S., but it has no commodity inputs for bitumen or dilbit, only “crude oil.”

Minnesota plans for an emergency

In 2015 Minnesota adopted statues that require rigorous contingency planning on the part of pipeline operators and railroads. “There’s been nothing comparable on the books before the statues,” says MPCA’s Doug Bellefeuille, who oversees the state’s emergency preparedness training.

In the past, he says the approach was prescriptive; “companies were told, ‘if you spill, you clean it up.’ ”

That’s not the case now. Under the statues, response plans must be submitted, reviewed and approved by the state in advance of an accident, with worst-case discharges calculated and designated personal and equipment ready to go. Plans must also describe: “the training, equipment testing, periodic drills, and unannounced drills that will be used to ensure that the persons and equipment described in section 115E.03, subdivision 4, are ready for response.”

The statues represent a vast improvement over past practices, but they still fall short in the same way PHMSA’s regulations do: No one is preparing for a diluted bitumen spill — at least on paper. Worst-case discharges, for example, are currently calculated using formulas for crude oil.

Whether a spill involves crude oil or dilbit makes a crucial difference in initial actions. Dilbit can be up to 50 percent diluent by volume. When it spills, the lighter components evaporate quickly (or “volatilize”), representing an immediate inhalation risk. Once the diluent separates, what is left is bitumen, which is denser than water.

Knowing with certainty that a spill involves dilbit means first responders can designate evacuation zones protective of human health and, if there is water nearby, prepare for the eventuality of submerged bitumen.

The ambiguity of whether a pipeline carries crude oil or dilbit may be clarified soon. In December, the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) released a study on the effects of bitumen on the environment and made recommendations for improving spill response. Results of that study, says PHMSA spokesperson Damon Hill, “will be important to help us determine if additional criteria to deal with diluted bitumen in oil spill response plans is needed.”

If the study has spurred on any potential revision, PHSMA can’t discuss it for now; it could be months or even a year before draft language is available to the public.

The comprehensive 180-page NAS study, in a nutshell, finds: bitumen is highly adhesive, and dilbit requires different oil spill response planning than other crudes. Namely, the study suggests spill response can be improved by “taking advantage of available information about diluted bitumen when it is spilled” as well as having accurate Safety Data Sheets on hand so that responders can more accurately predict the behavior of the spill. To that end, the study recommends the EPA and PHSMA work together.

Under the section on toxicity, the study said the potential of bitumen to sink in an aquatic environment “can result in unrecoverable sunken oil and thus prolonged chronic exposure of benthic organisms.”

Carys Mitchelmore, a contributor to the study, and associate professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, says “benthic organisms” refers to plants, fish, microbes and invertebrates, like worms and bivalves, “found on the bottom, or in bottom sediments of any water body.”

In addition, the study said, “the adhesion of residual bitumen oil to biological surfaces may lead to physical coating of organisms.” During the cleanup of the Michigan spill, plants and trees coated in bitumen had to be removed below and above the water.

Crew removes vegetation in response to bitumen spill in Michigan. (Photo: Dr. Stephen Hamilton)

Stephen Hamilton, also a contributor to the study, and professor at Michigan State University, says the removal of plants and trees occurred mainly in “slowly flowing backwater areas behind dams or in coves or oxbows. Most areas in the river system are less then 5 feet deep.”

“Above water, any plants and trees up to about 4 inches in diameter were removed if they were visibly oiled. They were cut off just above the soil surface.” Below water, oiled vegetation was removed “if the oiling was visible, or if the sediments were dredged.”

Trees removed following Michigan bitumen spill. (Photo: Dr. Stephen Hamilton)

For those concerned with the wild-rice ecosystem, it doesn’t take much imagination to extrapolate from the NAS study what might happen if diluted bitumen were to spill in Minnesota. While too much sulfate from mining represents a slowly evolving chemical imbalance detrimental to reproduction, bitumen represents blunt-force trauma.

Minnesota’s first responders

The location of spills can be hard to get to in Minnesota, and first responders often carry the weight until professional environmental cleanup groups hired by the company can get there. MPCA’s Bellefeuille describes the state as mostly rural, and says its first responders, with the exception of Duluth and the Twin Cities, are volunteers with other jobs. “They’re farmers, truck drivers, the guy who works at the hardware store.”

Since the state has become a superhighway for both dilbit from Canada and Bakken oil from North Dakota, regulators are hard at work preparing responders for transportation-related accidents. Training is currently provided by the Minnesota Department of Public Safety (Homeland Security Emergency Management) and the EPA. For rail incidents, PHMSA is offering training across the country, and recently completed one session at Prairie Island Indian Community.

For other tribal communities in Minnesota, says Bellefeuille, “Tribal officials are welcome to request training or attend any other training events.”

Tribal communities in Minnesota. (Source: Minnesota Department of Health)

DesJarlait says Minnesota’s numerous grassroots organizations are each comprised of diverse people and a broad range of causes. They often work as a coalition when concerns overlap. Protect Our Manoomin, for example, partners with Honor The Earth, Save Our Sky Blue Waters, Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness and WaterLegacy.

There’s strength in numbers, he says, but activism can be frustrating because the goalposts are always changing. “Multinational corporations are going to keep going until they get what they want.”

Thousands march through downtown St. Paul to the State Capitol in protest of the Sandpiper pipeline on June 6, 2015. (Photo: Jim Gehrz / Star Tribune)

Paula Maccabee, who serves as advocacy director and counsel for WaterLegacy, says industry often wins because “it has a lot more resources.” “Regulators would like to do something to protect the environment, but can’t always get there.” While regulators aren’t necessarily the problem, she says, they’re currently “also not part of the solution.”

Minnesota, with its abundant natural resources and geographical location, is at the crux of a modern dilemma. On one hand, people of the state need some form of economy to exist, and on the other, if water becomes polluted and a self-propagating food source is irredeemably harmed, what has been gained? Most people don’t live in a world where moving away from environmental destruction is an option.

For the Anishinaabe people, DesJarlait says, “Our responsibility is to protect the environment. Not just for one generation but for the seventh generation.” It’s a way of life that has served a long lineage of wild-rice families well: The food still grows after thousands of years.

Wild rice harvest. (Photo: Minnesota Historical Society Collections)