I live in a place called Forgottonia. Others call it McDonough County, Illinois. Four hours southwest of Chicago, 3 hours due north of St. Louis. An hour from the mighty Mississippi River. With 23 percent of the population living below the poverty line, we are one of the most impoverished counties in the state and no one seems to care outside of the 30,000 people who live here. Some who live here don’t care either.

To raise awareness of our plight I travelled to the Springfield Capitol, and once to Chicago, every Monday for 40 days, as part of the Illinois Poor People’s Campaign for Moral Revival. We are a movement that challenges systemic racism, poverty, the war economy, and ecological devastation. We took our inspiration, as the 50th anniversary of Dr. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign approached, from Rev. William Barber of North Carolina and Rev. Liz Theoharris, Co-Director of the Kairos Center. They picked up the campaign where King left off.

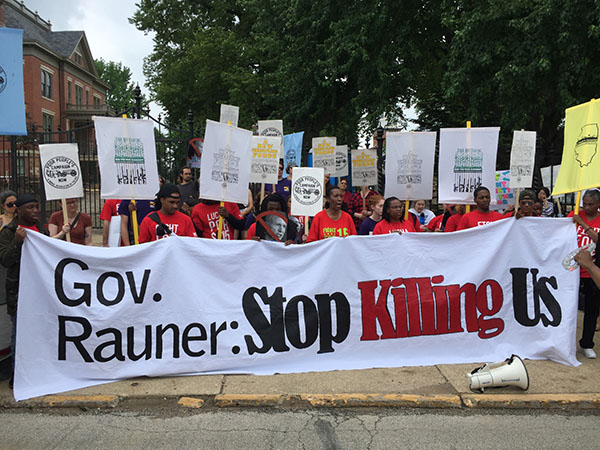

We rally and risk arrest to pressure state legislators and the governor to attack poverty. Most of the activists in Springfield came from Chicago, but poverty and its intersecting factors plague rural towns, as well, so I, also, made the 75-mile drive.

We began most Monday actions in Springfield with a march from the Service Employees International Union office to the Abraham Lincoln statue in front of the state house. We sang: Somebody’s hurting my people and it’s gone on far too long. We carried signs: Systemic poverty is immoral.

After we gathered on the steps, those among us who are poor told their stories about hard times. Trying to pay for health care and rent while working for minimum wage. Parenting children, keeping families together. Heaven forbid, they also want to drink clean water, breath clean air, and avoid gendered violence, gun violence, and police brutality.

After listening to these stories again and again, we marched to an intersection or entrance to government offices. Rev. Theoharris and Rev. Barber have encouraged campaigners to train in nonviolent civil disobedience. Barber writes, “When we get arrested, we do it to arrest the consciousness of the state and to guarantee that what we are doing will not be done in the dark” (quoted in Jaffe, p. 164.). In order to demonstrate our willingness to sacrifice for a better future for all, some 2,000 poor people, clergy, and allies from rural and urban areas in 40 states presented ourselves for arrest. On the mall in Washington, D.C., Rev. Liz Theoharris asked how many of us had risked arrest, and I, like most of the thick crowd around me, raised my hand.

In Illinois, moral witnesses supported those who blocked intersections and entrances with chants: Ain’t no power like the power of the people ‘cause the power of the people don’t stop, or, my favorite: Rauner vetoed $15, Veto Rauner ’18, but civil disobedience did not always result in arrest.

In fact, most Mondays, Illinois authorities refused to arrest us. For example, the first Monday in Springfield, Il, when activists blocked the intersection, capitol police trained to handle civil protest blocked the streets leading to the intersection, allowed the action to proceed for an hour, then ticketed protesters. Another Monday in Illinois, dozens of Fight For $15 protesters risked arrest by blocking the entrance to the senate gallery for over an hour, but left peacefully when individually warned by police. But in states such as Minnesota, Indiana, South Carolina, and Kentucky, authorities arrested activists from the first Monday of the campaign.

Police surrounded the direct action, but only arrested activists on week four, when we blocked the entrance to the Department of Healthcare and Family Services, a state institution that — along with public universities — received no funds due to Governor Bruce Rauner’s “gun to the head” style of “negotiating” with the state legislature.

The preamble to the Illinois Constitution specifically articulates the state’s vital role in providing for health, eliminating poverty and inequality, and assuring legal, social, and economic justice. Both down-state and in Chicago, however, Illinois is failing to realize its stated values. Rauner’s radically conservative agenda is responsible for much of this failure.

In 2015, when Rauner became governor, he promptly forced Western Illinois University (WIU) (and other state universities) out of the state budget, and cut taxes. The poverty rate, of McDonough County, already high, climbed to almost 24 percent. WIU cut jobs and now, at -1.8 percent from July 2016 to July 2017, McDonough County has one of the highest depopulation rates in the state. Since 2004, WIU enrollment has dropped 40 percent from 13,558 to a projected 8,000 for Fall, 2018. When enrollment drops, both students and WIU employees leave the region.

As professionals are laid off and forced out of the region and the state, we struggle to recruit enough volunteers to stock the local food pantry. More than 40 percent of students in the school district qualify for free or reduced lunch. Local businesses falter or fail. Homelessness is worse than I have seen since I first moved to Macomb 30 years ago. Health and social problems plague the area: newspapers report unprecedented violence, and drug sales appear to have replaced lawful work.

For more than a decade I worked as a professor of Women’s Studies at WIU, in Macomb, the McDonough County seat. Two years ago, WIU eliminated the departments of Women’s Studies and African American Studies (along with Philosophy and Religious Studies), conferred me with tenure, and fired me, all in one month.

Just as our current Poor People’s Campaign is an intersectional movement — because poverty affects people in various sectors of society — Women’s Studies is an intersectional area of study. More than 90 percent of the students in my classes were women. Most of them could not afford books. Many were so financially pressed that they often missed class to work. Most were women of color. Many of them came from Spanish-speaking homes. Many were LGBTQA. These are the voices the PPC seeks to amplify.

When WIU fired me, I no longer could teach my students, no longer could guide them in the study of social inequalities: sexism, racism, and a host of other intersecting factors that block their — and our — pursuit of happiness. I was the only faculty member at WIU who taught classes on Hispanic Women and Women and Creativity. WIU students no longer have access to these classes.

While the Women’s Studies department was killed, WIU expanded its Law Enforcement program, including a minor in Homeland Security, named for the department that houses ICE.

In his 2016 memoir, Rev. Barber writes, “King’s turn against the war in Vietnam and towards the Poor People’s Campaign in the last year of his life was an acknowledgement of America’s deep need to recognize how military spending abroad was connected to poverty at home.” Today, the United States. has extended military spending to weapons and surveillance at home, even in Macomb, Ill.

This pattern of cutting public funds in the liberal arts while spending more in military, police, and surveillance, is a prime example of the critique Dr. Martin Luther King espoused in the late 1960s: We invest in war and violence at the expense of the common person’s ability to pursue happiness and benefit from domestic tranquility. During Monday actions for the PPC, we carried signs that read, “The War Economy is Immoral.”

In Macomb, while there’s money for weapons, we struggle to fully fund our K-12 schools. We have not been able to pay for sexual assault prevention training for our teachers, principals, staff, and students. The Macomb school district faces a $10-million-dollar sexual assault lawsuit. If the district loses, it is not clear how they would pay out. We could lose our school and be forced to bus children to another rural school that suffers even more than we do. With adequate investment in sexual assault prevention, of course, this lawsuit might have been prevented.

In my last few years at WIU, I frequently dodged leak-catching trashcans in classrooms, hallways, and bathrooms. Even STEM fields are underfunded: the UPI has reported that our science labs desperately require safety updates.

When the state invests in rural Western Illinois, our community thrives, housing is affordable, public-school students can excel, and we give back to the state. In some ways, the quality of life here is very good: Traffic is light, so our commutes are short, and thus we have time to cook dinner most nights and share a meal with others. Because the town is safe and small, our children can often walk to school; so can WIU employees. We have a farmer’s market, a food co-op, and two Community Supported Agriculture programs.

None of this is possible without WIU, our region’s economic engine. WIU and its employees provide an affordable university education to students from all across Illinois (half our students come from the Chicagoland area), the United States, and the world. In addition, WIU offers plays, musicals, recitals, and sports events that the community can enjoy.

While the poverty rate in rural Illinois is climbing, poverty is not inevitable. With adequate state funding for WIU, along with the ability to fully fund our public schools and healthcare for everyone, we can lower the poverty rate.

We will not be forgotten! That is why I traveled to Springfield, where I joined with other people from across Illinois who refuse to accept the status quo. The richest country in the history of the world does not have to have any poor people.

We are a fusion coalition movement: Rural and urban, black and white, women and men, queer and straight — poverty exists among all these American groups and many others. Like the Reverends King, Barber, and Theoharris remind us, poverty is a moral matter. We shall not give up our fight to ensure that poor people in our rural, downstate communities — even in Forgottonia — are not forgotten!