Following the Republican National Convention, this week’s featured stories reflect on the politics of rural America, especially in relation to the candidacy of Donald Trump. They also examine ongoing federal efforts to expand healthcare and enhance broadband access in rural areas, the growing demand for organic produce and the ongoing controversy surrounding pipelines and tribal sovereignty on Ojibwe lands in the Midwest. In addition, we learn about the sustainability of seaweed farming in the northeast.

On Trump’s appeal

An Associated Press article by Claire Galofaro explores the reasons for Donald Trump’s popularity in Appalachia, finding that many of the Republican candidate’s most ardent supporters live among the coalfields:

There are places like this across America — poor and getting poorer, feeling left behind while the rest got richer. But nowhere has the plummet of the white working class been as merciless as here in central Appalachia. And nowhere have the cross-currents of desperation and boiling resentment that have devoured a presidential race been on such glaring display.

The story features quotes from several struggling Trump supporters. Mike Kirk, for example, who works at a pawnshop for $11 an hour, less than half what he made in the mines, says that Trump “offers us hope, and hope’s the one thing we have left.” Ashley Kominar’s husband lost his job in the mines, and the 33-year-old mother of three faces tough economic choices. About Trump, she says: “I don’t know exactly what’s in his head, what his vision is for us…but I know he has one and that’s what counts.”

Read “In Desperate Parts of Appalachia, Trump is a Desperate Survival Bid”, here.

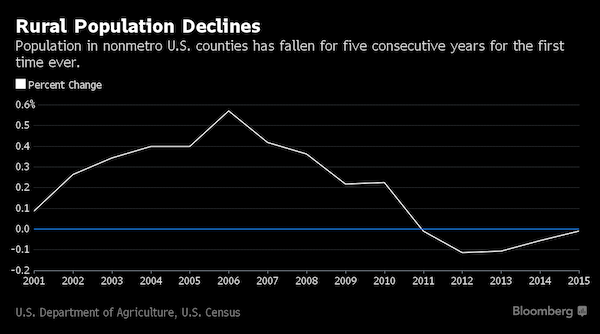

Meanwhile, Bloomberg reports that Trump’s message has also resonated in rural Ohio. Their coverage includes interviews with several residents of rural Meigs County, where Trump beat former Ohio Governor John Kasich 47 percent to 33 percent. In this county, as in other rural areas, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) has taken lead in providing social services. But while the agency uses federal funds to help Meigs County reinvent itself, its citizens tend to support Trump. “I like Trump because he’s never held political office,” says Judy Sisson, a retired court clerk and treasurer of the local Republican Party. “He’s scary, but he’s making people say ‘Oh my, we can’t do business as usual.’ ”

Read “In Backyard of the RNC, Drugs, Vanishing Jobs Strain Rural America” here.

Healthcare and illegal drugs

This week saw multiple developments in federal rural health policy. Minnesota newspapers report that Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) is pushing three bills to improve health services in rural areas. The first would provide residents more ways to travel to health services as well as increase broadband funding to allow rural residents to communicate with doctors online. The second would try to lure more doctors and medical professional to rural areas. The third would seek to increase payments to rural health professionals and hospitals to bring salaries closer to those at their urban counterparts. “I don’t think it should be part of living in beautiful rural Minnesota that you have worse health-care quality,” says Franken.

Read “Franken Aims to Help Rural Health” here.

In Washington, The Hill reports, the Obama administration is allocating $9 million to rural health officials in Colorado, Oklahoma and Pennsylvania to help them deploy a tele-medicine-style training program in an attempt to stop increases in overdose deaths. The states will use the Project ECHO model, which was developed by the University of New Mexico to treat hepatitis C, to allow rural primary care doctors to watch videos by urban specialists trained in issues like opioid addiction. A study published recently in Substance Abuse journal concluded that the model is well-suited to expanding anti-addiction treatment “particularly in underserved areas.”

Read “New Federal Grants to Help Rrain Rural Doctors to Fight Addiction” here.

Agriculture, terrestrial and otherwise

In Maine, The Portland Press Herald reports that the 2nd annual Seaweed Festival, held in South Portland, has been cancelled. Seaweed is widely used in the production of snacks, soaps and dog food and the state is the country’s largest producer. The festival, which started in 2014, doubled in attendance to 3,000 last year. Maine’s seaweed industry quadrupled its harvest from 2004 to 2014 and the festival is not happening this year due to planners’ concern over a lack of sustainability:

Organizer Hillary Krapf, who runs a seaweed products and education company called Moon And Tide, said Maine’s seaweed industry has been besieged by a “Gold Rush mentality” that threatens sustainability as seaweed grows in popularity. New players are getting involved in Maine seaweed farming before there is anywhere near the infrastructure needed to sustainably process and sell it,” she said.

“I would like to see more regulation and accountability. We can feel good about what we are promoting and make sure we are doing right by the ocean and its resources.”

Read “Rift Over Sustainability Leads to Cancellation of Maine Seaweed Festival” here.

The number of wild-seaweed harvesters in Maine has held steady at around 150 to 170 for the last few years, and there are a handful of aquaculture seaweed farmers. (Cation / Photo: Press Herald)

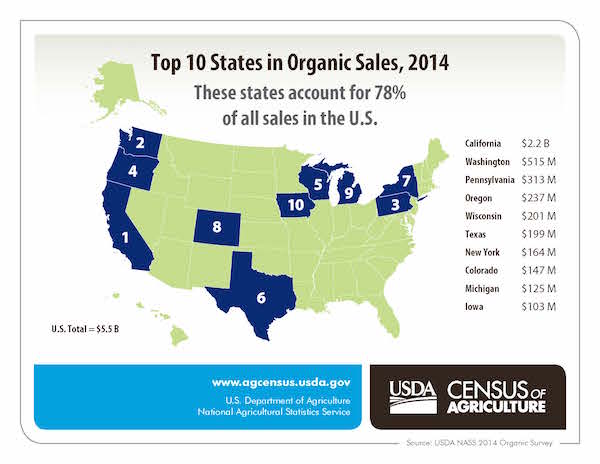

Organic farms, on the other hand, are sustainable. But, according to The Guardian, American farmers are struggling to meet growing demand. The USDA estimates that only one percent of the nation’s cropland qualifies as organic but that, according to Euromonitor, consumer appetite for organic foods has grown to an estimated $13.4 billion in the United States, up from $12.8 billion in 2014. The problem is significant:

The time and expenses required to get organic certification present major roadblocks for increasing the amount of organic farmland in America. It’s a problem not just for farmers but for food companies that are trying to meet an increasing consumer demand for organic products. The concern for a shortage of organic produce and ingredients is so acute that several corporate businesses and nonprofits launched new efforts recently to give growers better incentives to go organic.

“When you look at the percentage of the marketplace, what consumers are buying versus what farmers are producing, farmers aren’t producing as much organic as consumers are consuming,” said Alexis-Badden Mayer, political director of the Organic Consumers Association, an organics advocacy group.

Read “American Farmers are Struggling to Feed the Country’s Appetite for Organic Food” here.

Rural broadband access

Broadband remains a persistent theme in rural journalism and, according to the Brookings Institute, the divide between rural and urban broadband access remains large. Despite recent efforts to close the gap, this report finds that “new rules fail to rectify existing inequalities between urban and rural communities”:

The FCC in 2015 redefined broadband as connections with 25 megabits per second (Mbps) download speeds and 4 Mbps upload speeds. This is more than six times the previous standard of 4 Mbps download, allowing for multiple simultaneous video streams. According to the FCC’s 2016 Broadband Progress Report, 10 percent of Americans lack access to broadband by this definition. This number, however, fails to illustrate the stark contrast between rural and urban access to broadband. Rural areas have significantly slower internet access, with 39 percent lacking access to broadband of 25/4 Mbps, compared to only 4 percent for urban areas. This rural/urban “digital divide” in access severely limits rural populations from taking advantage of a critical component of modern life.

To end this digital divide, the article argues, the FCC must do more. The FCC has expanded the Connect America Fund, providing broadband access to over 7 million people over 6 years. But the Brookings report adds that the federal government must also expand access as technologies are developed that demand faster speeds.

Read “Rural and Urban America Divided by Broadband Access” here.

Tribal sovereignty vs. pipelines

Indian Country Today Media Network (ICTMN) reports ongoing concerns of oil pipelines running through Native American lands in northern Minnesota. Ojibwe tribes are preparing a legal challenge in an effort to reaffirm the hunting, fishing and gathering rights guaranteed in their 1855 Treaty with the United States. Other tribes have won in such challenges in the Pacific Northwest and the Great Lakes Region. Winona LaDuke, of the White Earth Ojibwe, executive director of Honor the Earth and a regular Rural America In These Times contributor, explains that the motivation is in part environmental:

“It is important that everyone understands the indigenous environmental justice focus of this challenge,” says Winona LaDuke. … “This landscape is threatened by two major pipeline proposals, Sandpiper and Enbridge Energy’s Line 3 Replacement, which could adversely affect the health of our people for generations. It is clear that neither the state nor these companies are going to voluntarily accept the existence of our legal rights.”

The pipelines travel through the 1855 ceded territory. If the Ojibwe prevail, Enbridge could be forced to pay compensation to tribes for damages from pipeline projects to wild rice waters and wildlife habitat.

Top, left to right: Joe Plumer, Attorney for the White Earth Band of Ojibwe; Archie LaRose, Board Chairman, 1855 Treaty Authority (he is Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe) ◦ Bottom L-R: Frank Bibeau, Executive Director, 1855 Treaty Authority; Dale Greene, Board Member, 1855 Treaty Authority. (Photo / Caption: ICTMN)

Read “Treaty Rights Battle Links Hunting and Oil Pipelines in Minnesota” here.

If you come across rural stories you think should be featured in Rural America In These Times’ next roundup, please send links to john@inthesetimes. Also, please follow RAITT on Twitter @RuralAmericaITT and:

On second thought, RAITT would be remiss if we failed to weigh in on the Pokemon Go phenomenon currently sweeping North America. In short, some people like it. Others don’t:

(Photo: Facebook)