The rural economy received some bad but then not-so-bad news in the second half of September. A Census Bureau survey at first suggesting that rural incomes had failed to increase along with those in the rest of the country was later revised. The following stories look at this report’s macro-economic snapshot, but also at how regional income disparities continue to weigh on infrastructure development — from education, housing, mental health to technological advancement — in certain rural areas.

We also include some assessments of how the rural economy may impact the 2016 presidential race.

“An honest mistake”

Census Bureau stats released on September 13 appeared to indicate that rural (non-metro) areas had been “left behind” by a national trend of income growth. But it was later determined that the results were improperly skewed due to recent changes in how some metro and non-metro areas are defined. These changes were not factored into the survey’s initial analysis.

The Current Population Survey (CPS) first reported that, outside of cities:

- Median household income fell from $45,534 in 2014 to $44,657 in 2015, after adjusting for inflation, though the decline was not statistically significant.

- The official poverty rate rose from 16.5 percent in 2014 to 16.7 percent in 2015, though the increase was not statistically significant.

The findings prompted The New York Times to launch a debate — “Helping Rural America Catch Up” — that framed the subject this way:

The latest economic data show the largest growth in real income and the greatest drop in poverty in years. But the biggest gains have been in the large metropolitan centers, and millions of Americans in rural communities and small Rust Belt towns still feel left behind. As Ralph Kingan, the mayor of Wright, Wyo., put it: That economic growth “ain’t out in the West.

But then, last Monday, the Census Bureau acknowledged the demographics oversight and announced that they were removing the survey’s comparison between 2014 and 2015 rural incomes — calling them “not comparable.”

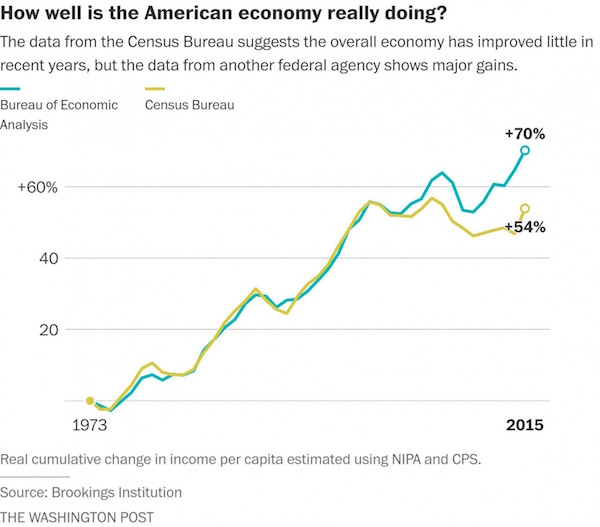

In “Census Bureau Retreats from Report Showing Stagnant Rural Incomes,” The Washington Post explained:

The flawed estimates were based on the bureau’s Current Population Survey, one of several surveys conducted regularly by the bureau. The problem resulted from how, as the population grows and Americans move from one part of the country to another, the bureau must adjust the boundaries that define metropolitan areas. These adjustments, carried out every decade, altered the map for the Current Population Survey last year.

Arloc Sherman, a researcher at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, said, “It is, in essence, a retraction.” He added that the census had apparently made “an honest mistake.”

The confusion left numerous news outlets to clarify their earlier reports. In “Correction: In Another Census Report, Rural Incomes, Poverty Improved,” the Daily Yonder’s Tim Marema writes:

It turns out, median household income in nonmetropolitan America actually increased from 2014 to 2015, from $42,698 to $44,212, according to figures from the American Community Service and reported by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. That’s an increase of 3.4 percent, and is roughly on par with the income increase in metropolitan areas during the same period of 3.6 percent.

Similarly, the non-metro poverty rate improved by 0.9 percentage points, to 17.2 percent in 2015.

This is not to say that the report indicates a rosy picture for nonmetro America versus metropolitan American. The gap between nonmetro and metro median household and poverty remained flat. That means that rural American continues to lag significantly behind the rest of the nation by these economic measurements. (See more about the interpretation of the poverty rate below.) But the problem didn’t get worse from 2014 to 2015….

Rural housing

Even if rural incomes are not as stagnant as first reported, a number of rural areas are experiencing a housing crisis. “The Other Housing Crisis: Finding a Home in Rural America” in YES! Magazine explores why too many Americans are encountering trouble when it comes to home ownership:

The people most affected by the lack of good quality housing are low-income residents who can’t afford mortgages with high-interest rates. And those who do own houses often make such low wages that they’re unable to secure loans to repair their deteriorating homes.

About 21 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, according to the Housing Assistance Council. Nearly 30 percent of them reside in substandard housing with leaky roofs or inadequate plumbing. Rural families are more likely to be impoverished than the rest of the nation, and about half of them spend 50 percent of their monthly income on rent.

Homeownership is a crucial step to building wealth, but national banks that offer home loans to homebuyers are few and far between in rural areas. They have little incentive to serve low-income, low-density populations.

“Your choice is limited. You can imagine — there aren’t that many people in rural areas, and there certainly aren’t enough banks,” said David Dangler, director of the Rural Initiative at the affordable-housing advocacy group NeighborWorks America.”

Melissa Hellmann’s article also focuses on the efforts of affordable-housing groups in West Virginia and California that are trying to address these shortages.

Solastalgia in coal country

Economic hardship can cause psychological and social distress. In her article, “As Coal Mining Declines, Community Mental Health Problems Linger,” Georgia State University professor Roberta Attanasio found “plenty of clues suggesting that health and mental health issues will pose enormous challenges to the affected coal communities, and will linger for decades.”

One such mental health problem is known as solastalgia:

Although not everyone is susceptible to these effects, people who gain a strong sense of identity from the land are most likely to experience negative outcomes. Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term solastalgia as “a feeling of chronic distress caused by negatively perceived changes to a home and its landscape,“ which he observed in his native Australia due to the effects of coal mining.

People who experience solastalgia lack the solace or comfort provided by their home; they long for the home environment to be the way it was before. In a study of Australia published in 2007, Albrecht and collaborators documented the dominant components of solastalgia linked to open-cut coal mining in the Upper Hunter region of New South Wales – the loss of sense of place, the feeling of threats to personal health and well-being, and a sense of injustice and/or powerlessness.

The Kayford Mine near Charleston, West Virginia, photographed in 2008. (Photo: DDIMICK / FLICKR)

More diverse local economies are seen as a key factor in the recovery of regions struggling with high unemployment. In states like West Virginia and Kentucky, the question is: What will replace coal? In his article, “A Different Kind of Holler: Appalachia’s Future is Looking A Lot More High-Tech,” Tom Eblen of the Lexington Herald-Leader found some cause for optimism after attending a recent technology conference in coal country:

I have attended many conferences in the past two decades about creating a more diverse economy in Eastern Kentucky to replace the long-anticipated collapse of the region’s coal-mining industry….

Fortunately, things are changing. That was evident in the presentations Friday that attracted more than 200 people to Hazard Community and Technical College called Big Ideas Fest for Appalachia: Visionary Thinking and Doing.

The best parts of the conference were the reports from students and teachers about how they are learning new technology — from middle school kids building computers at home with help from online videos to Morehead State University students building tiny satellites for NASA space missions.

Also on the subject of education, a University of Georgia professor recently interviewed 26 African-American students and workers in a rural Southern high school and published what he found in The Review of Higher Education. You can read “Overlooked, Black Students in Rural Areas Face Unique Challenges, Says UGA Researcher” here.

#Election2016

As polls between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump tighten, numerous articles have sought to explain Donald Trump’s undeniable appeal to rural voters. Despite reports of his affinity for gold-plated bathroom fixtures (but not toilets), Trump’s campaign rhetoric is often critical of the American elite and this resonates with many rural, working-class voters. One story in U.S. News & World Report suggests that:

To understand why rural America believes their savior is a Manhattan real-estate mogul and not a Yale-trained policy expert who helped improve schools in a poor state like Arkansas, however, is to understand the American fault lines of class, authenticity and elitism, including how politicians see the rural poor – and how the rural poor see themselves.

At the same time electoral math and the red-blue political divide also means neither party is likely to seriously address the needs of the rural poor in the South and the heartlands – so-called “flyover country,” where Democrats haven’t been competitive since President Lyndon Johnson came to ramshackle Inez, Kentucky, in 1964, to launch his War on Poverty campaign.

J.D. Vance, author of the best-selling memoir, “Hillbilly Elegy,” believes the reason Trump is big in small town America lies with attitudes of “political elites” like Clinton and President Barack Obama, her onetime rival and former boss. Though they have great policies and are well-intentioned, Vance said, they don’t seem to respect or empathize with rural poor people.”

Read “Penthouse Populist: Why the Poor Love Donald Trump” here.

Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis by J.D. Vance. (Cover: goodreads.com)

Another article, this one from FiveThirtyEight, suggests that Trump’s support in rural Maine, which could win him an electoral vote, might be due to a cultural and economic disconnect:

This might be because Trump has helped vocalize what it feels like to be disconnected, not just from economic progress but from the rapidly changing technological culture of America in the 21st century. That feeling is plain in the 2nd District. It can be difficult to live in many parts of northern Maine and easy to feel left behind.

Read “Trump’s Appeal to Rural Voters May Win Him an Electoral Vote in Maine” here.

In other news, it appears some voters are turning their backs on Hillary Clinton, albeit temporarily:

The selfie generation. (Photo: Twitter)