Though the rural-urban divide has existed for decades, it is more pronounced now than it has been in generations. Our geography enforces an “us vs. them” dichotomy that, for many on both sides, makes political, economic and cultural differences seem stark and simple. But the divide is more complex than many realize, and the slang too often used to describe rural Americans is imbued with contradictions.

When President Trump won the election, understandably frustrated opponents fell back on words like “hillbilly,” “redneck” and “white trash” to describe his rural voter base. Yes, Trump won most of rural America’s votes, but what do these words really mean, and why do people use them?

In short, they are convenient. Stereotypes revolve around the process of “othering,” which occurs when people mentally characterize an individual or members of a group as outsiders. Rather than accept other people as complex individuals, like we see ourselves, sometimes it can be easier to generalize and dismiss them as less than fully human. But when “hillbilly,” “redneck” or “white trash” is used to distance oneself from the rural “other,” the fact that these words have fluid meanings and deep histories is conveniently ignored.

Hillbilly

According to the Oxford Dictionary, the word “hillbilly” is defined as “an unsophisticated country person, originally associated with remote regions of Appalachia.” Common stereotypes associated with a hillbilly include someone who is uneducated, poor or armed with rifles. The stereotype also extends to characterize the morality of hillbillies, often associating them with inbreeding, alcohol abuse and violence.

However, the word “hillbilly” did not always have negative connotations. When Scots-Irish people immigrated to America, many of them settled in Appalachia. The word “hillbilly” originally came from their words “hill” and “billie,” which was a synonym for fellow. So, in the early 20th century, “hillbilly” simply meant “hill folk.” Hillbilly music, now known as folk music, originated in Appalachia, and was characterized for its use of the fiddle, banjo and guitar. However, the term soon took on more meaning, as the Scots-Irish became famous for their tightly knit clans and family structures. Thus, the term “hillbilly” was associated with tradition, independence and strong home values.

But because the Scots-Irish clan structure was so tightly knit and because geographic isolation lent itself to poverty and, eventually, post Civil War struggles, the region grew more insular. And soon “outsiders,” or people not belonging to Scots-Irish clans, began to simplify, generalize and stereotype this complex group of people.

In his book, Hillbilly Elegy, J.D. Vance comments on the complex contradictions of the term: “This distinctive embrace of cultural tradition comes along with many good traits — an intense sense of loyalty, a fierce dedication to family and country — but also many bad ones. (Hillbillies) do not like outsiders or people who are different from (them).”

Vance writes about aspects of the hillbilly that apply to his family. He was, for example, taught that “hill people” and “poor people” generally meant the same thing. But he also speaks to the complexity of this language and takes pride in his hillbilly ancestry — viewing his family as “hillbilly royalty” and admiring their sense of “hillbilly justice.” This involves “good vs. evil” stories of family members who punched someone for insulting their mother, stood up to their sister’s bad boyfriend or made a criminal pay for his crime. For Vance, the word “hillbilly” is not good or bad, but rather a complex term steeped in class and stereotypes.

Redneck

Like “hillbilly,” the word “redneck” is also loaded with contradictions. The Cambridge Dictionary defines “redneck” as a poor white person, without education, especially one living in the southern United States, who is believed to have prejudiced ideas and beliefs. The term has since evolved to characterize any working-class white racist from any rural region. But when “redneck” was originally coined, it was not pejorative. First used in South Africa in the late 19th century, “redneck” described any Englishman and was “drawn from the fact that the back of an Englishman’s neck is burnt red by the sun.”

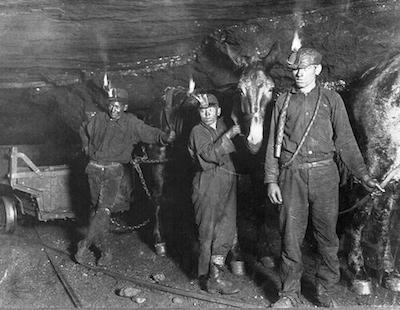

The term gained its political connotations in the 20th century when miners fought the industry that was exploiting their rights. They wore red bandanas around their necks to identify themselves with the pro-union movement. In this sense, many southerners claimed the term “redneck” as a badge of political pride. In the 1970s, “redneck” became a fashionable term. “Redneck chic” was a fad where trendy white Americans dressed up in Levi’s and cowboy boots, sipped Lone Star and watched hit western movies, like Urban Cowboy. “Redneck” became a symbol of class patriotism and authenticity.

An archived photograph of West Virginia coal miners. (Image: wvpublic.org)

The word has evolved considerably since then, though. Now, “redneck” is politically charged, as it is associated with President Trump. Many urban people use the word “redneck” to denounce rural people who they think are prejudiced or hold retrograde political beliefs. But using a stereotype to fight prejudice is illogical and counterproductive. Calling someone a redneck does not distance urban people from rural America; it does not make them more educated or politically informed. On the contrary, the word reveals urban American’s own prejudices and hypocrisy.

In short, using a word, like “redneck” to insult a rural person for having prejudicial beliefs is like calling somebody else “lazy” as you recline on a couch, eating potato chips.

White trash

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines “white trash” as a phrase that is usually disparaging or offensive: “a member of an inferior or underprivileged white social group.”

According to Nancy Isenberg, the author of White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, the phrase first appeared in newsprint in the 1820s. However, in an interview with PBS, Isenberg suggests that the phrase’s meaning has a much deeper history. She says, “if we go back to some of the leading promoters of British colonization, when they imagined what were they going to do with the new world, the new world…was imagined as a wilderness, what they called a wasteland.” Isenberg describes this new world as the “perfect place for literally dumping the idle poor, and these people were referred to as waste people.”

It is ironic that many people use the words “hillbilly, “redneck” and “white trash” in attempt to simplify groups of people when, in reality, the connotations and etymologies make these words complex. “Hillbilly” can be associated with folk music and poverty; “redneck” can mean both political pride and political prejudice, and “white trash” can denote the prejudices of both colonial and present day ruling class culture. Because this derogatory language is riddled with contradictions, people’s attempts to distance themselves from rural America through “othering” ultimately fail.

Furthermore, when people dismiss the history and fluid definitions of “hillbilly,” “redneck” and “white trash” — when they use these words as stereotypes, specifically aimed at disparaging people who live in rural areas — they shamefully reveal the depth of their own prejudices.

The idealized rural

It should go without saying that not all urban people use derogatory language when talking about rural America. But sometimes even idealized language further complicates the rural-urban divide.

Take, for example, classic literature. Many of America’s most respected writers idealized the natural, rural world. For many literary icons, rural places are associated with agency, thought, reflection and freedom. Henry David Thoreau wrote, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately.” Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “I have no hostility to nature, but a child’s love to it.” And John Muir: “The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest of wilderness.” Or Leonardo Di Vinci: “I roamed the countryside searching for answers to things I did not understand.” And, finally, Oscar Wilde: “Anyone can be good in the country.”

Though these words were written in the past and the writers themselves have passed, we continue to learn from classic literature because the themes and lessons are timeless. As The New York Review of Books puts it: “a classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.” But not only is the idyllic rural represented in literary classics, it is prevalent in today’s culture.

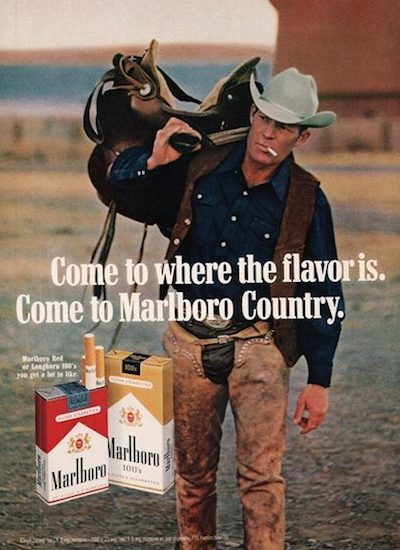

Marlboro’s iconic “Marlboro Man,” for example, used the image of a cowboy to sell cigarettes. Some ads showed a chisel-faced cowboy smoking, leaning against a classic red barn, or a stoic cowboy leading his horse through a snowy meadow, shielding his cigarette light from the wind. The ads evoke ideas of American grit, manliness and boldness. Some ads were accompanied by the slogan: “Come to where the flavor is. Come to Marlboro Country.” Of course, “Marlboro Country” is not an actual place; rather, it is representative of any glorified rural place. Additionally, the repetition of the word “come” invites viewers to be part of this rural image — even if they live in a city. According to the ad, in order to “come to Marlboro Country” and identify with a gritty cowboy, all one must do is buy a pack of cigarettes. And this logic worked. The Marlboro Man quickly became the most powerful mascot in American tobacco marketing history. One year after his 1954 debut, sales hit $5 billion — an over 3000 percent increase.

The Marlboro Man was not a hillbilly nor a redneck, and he certainly wasn’t white trash. Rather, his stoic image and popular slogan capitalized on people’s tendency to idealize, and even idolize, aspects of rural America.

An advertisement featuring the now infamous Marlboro Man. (Image: adaholic.com)

Advertisements and literature are not the only places where people use language to romanticize rural America. Another example is the popular “Farm-to-Table” movement, which promotes the sourcing, selling and serving of local food. Also known as Farm-to-Fork, it is currently one of the culinary world’s biggest trends. While the movement has become somewhat controversial due to a debate over the true meaning of “local,” its popularity is undisputable. In 2014, local foods generated $11.7 billion in sales and, according to Packaged Facts, a market research firm, they are expected to rise to $20.2 billion by 2019.

Of course, there are many reasons people like to eat local food: they want to support small farmers, they believe it tastes better and that the food is healthier. But another reason many people support this movement is revealed in its name — Farm-to-Table. It is not called “Farm-to-Factory-to-Table” or “Farm-to-Food Plant-to-Processing-to-Packaging-to-Table.” Rather, restaurants are employing simplified language to portray the rural as natural, healthy, and above all, close.

For good reasons, people like the idea that their food has fewer miles to travel between a local farm and their table. Because local food travels short distances, farmers can focus on making it healthier, rather than focusing on making it resilient to long travel periods. According to a study performed by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University, produce in the conventional system travels an average of 1,518 miles from a farm to a consumer. By contrast, locally sourced food travelled an average of 44.6 miles.

This sense of closeness, as represented through both the “Farm-to-Table” movement and name, directly contrasts urban people’s attempts to distance themselves from the rural through the language of stereotypes. In other words, although people like to believe that their food is close, that the Marlboro Man’s image is attainable, and that literary legends guide their studies, people who use stereotypes to describe rural Americans simultaneously prefer hillbillies, rednecks and white trash Americans be as far as possible from their table.

Ultimately, whether urban people want rural Americans to be close or far, one thing is true: for better and worse, the farms (family and corporate), the Marlboro Man, the famous writers, and derogatory stereotypes are all part of what defines rural America. Furthermore, it is not up to anyone to decide whether rural America is “far” or “close,” or whether it should be criticized or idealized. Rather, it is everyone’s responsibility to understand that the rural-urban “divide” is complex and not as stark as we may have thought.

Nora Mabie is the Indigenous affairs reporter at Montana Free Press. She previously covered Indigenous communities at the five Lee Montana newspapers, the Missoulian, Billings Gazette, Helena Independent Record, Ravalli Republic and Montana Standard. Prior to that, she covered tribal affairs for the Great Falls Tribune. Nora is a graduate of Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism. Reach her at nmabie@montanafreepress.org.