How Ferguson’s Black Majority Can Take Control of Their City

Our analysis of the voting data shows that when only white people vote, only white people get elected.

Amaris Montes and Zack Avre

As we approach the midterm elections, many analysts are suggesting that our usually low midterm turnout — averaging about 2 in 5 eligible voters in recent decades—may dip even lower. That’s despite these elections drawing more spending than any midterm election in history.

But the picture is even worse in local elections — not only in numbers, but in equity in demographics such as age and race, raising serious questions about the disengagement of a growing number of Americans from their municipal governments. Most local elections in the United States are held in odd years, apart from elections for state and federal government, often at times of the year that many people don’t associate with voting.

Take Ferguson, Missouri, where there is continued unrest in the wake of Michael Brown’s shooting by a police officer. Only three out of 53 police officers and one out of six council members are African American in the nearly 70 percent black city. The distorted makeup of the City Council and police force have led many to ask: Why does Ferguson’s city government not reflect the city it represents?

Using L2’s VoterMapping software, we traced voter turnout in Ferguson in all elections since 2008, paying particular attention to disparities among racial and age groups. Our findings confirm that voters in Ferguson’s elections are significantly older and whiter than the presidential election electorate and adult population.

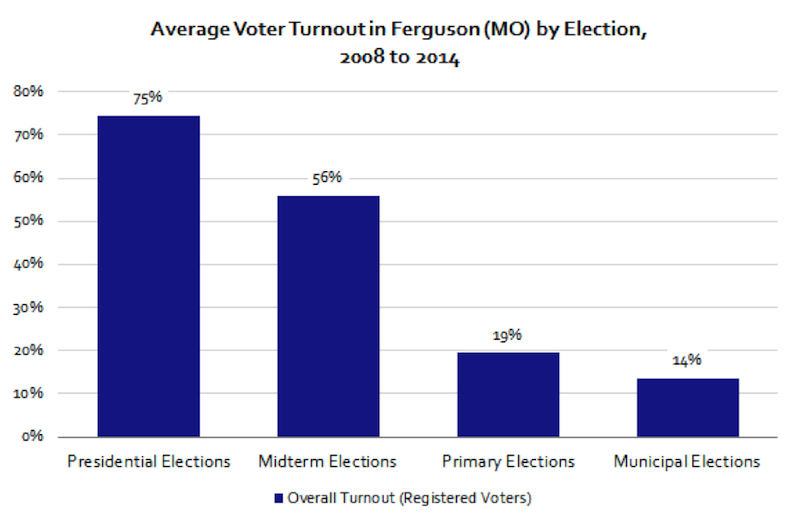

The problem of an unrepresentative government starts with low overall turnout in Ferguson’s municipal elections, which are held in April. Take a look at how Ferguson’s turnout in municipal elections compares with other elections.

Those who do turn out are highly unrepresentative of the community. In the 2010 census, 2 in 3 residents of Ferguson were African-American, yet they made up only about one-third of voters in the past seven city elections. White voters made up over 50 percent of the electorate in local elections over the same period. The presidential elections, while not precisely representative, came closer, with only 38 percent white voters.

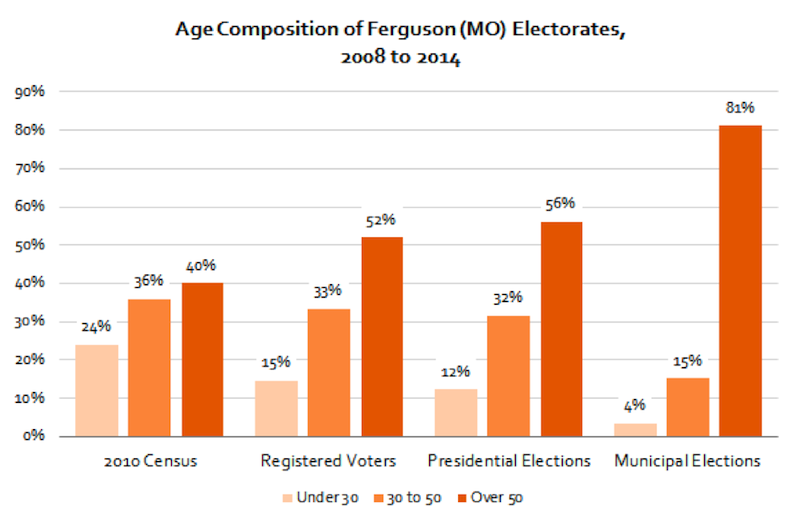

The disparity among age groups is even more striking. Three-fifths of eligible voters in Ferguson — a super-majority — are under 50. Yet this demographic made up less than 20 percent of voters in the city’s municipal elections. Voters ages 18 to 30, in particular, are merely 4 percent of the electorate in city elections. That represents a sixth of their share of the voting age population and a third of their share of the presidential electorate.

Residents over 50, on the other hand, make up a staggering 80 percent of voters in Ferguson’s local elections We estimate that the median age voter has been 63. Much attention has been paid to the racial disparities in voter turnout, yet the issue of civic engagement and representative government is clearly a matter of both race and age.

Disconnects between communities and their local governments are not isolated to Ferguson. As part of a broader analysis of distortions in electorates in local and primary elections, we have found that local elections skew heavily to older, whiter voters. In Gainesville, Florida, for example, voters under 30 make up more than a quarter of registered voters, yet only 6 percent of voters in city elections.

The problem of low and unrepresentative turnout in low-profile elections is getting worse. The Center for the Study of American Electorate reported that of the first 25 states holding primaries this year, 15 hit historic lows, with their overall turnout barely half of what it was in their 1966 primaries. Our analysis of municipal election turnout shows staggering declines over the past decade, leading to turnouts of less than 15 percent of registered voters in recent mayoral elections in Dallas, Houston, Austin, Miami, Baltimore and Chapel Hill, North Carolina and in single digits in El Paso and San Antonio.

To combat the turnout problem, we must think systemically. The date of elections is the easiest factor to change. Moving municipal elections to November of even years to coincide with congressional elections would lead to far higher and more representative turnout. Better civic education should start in schools and extend to innovative voter guides. Ranked choice voting would give voters real choice and opportunities to win fair representation addressing the disillusionment and disconnection that contributes to low and inequitable turnout.

Every community will have its own solutions, but it’s time to act. Such turnout disparities are simply unacceptable — and as shown in Ferguson, have real consequences. Every single individual is affected by the results of municipal elections. When fewer than 1 in 5 people and even smaller shares of young adults and people of color decide who makes budgets, appoints police chief and manages schools, can we really say we live in a fair democracy?

FairVote executive director Rob Richie assisted in this project.