The Will to Secede

With the re-election of Barack Obama, secession rears its head.

G. Pascal Zachary

From time to time, the breakup of the United States becomes appealing to many citizens — patriots of various stripes who “in the Course of human events” have come to believe that it is “necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them.”

We are in one of those periods now, and while the reasons are unique and the historical moment singular, looking backward at past episodes of secessionist zeal can help illuminate the present. Does the post-election outpouring of secessionist fervor exemplify a passing fancy? Or does it rather suggest a deeper, even revolutionary, change in the American political terrain?

The immediate trigger was Barack Obama’s victory, which heralded a new coalition of voters — women, people of color and young people — who voted for the Democratic candidate at such a rate that, given the prevailing demographic trends, the Democratic Party appears to possess a major advantage for the foreseeable future.

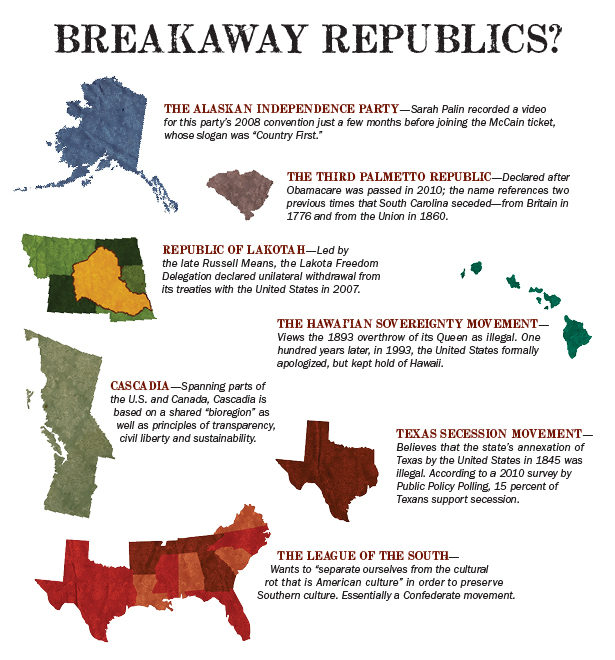

After the election, right-wing activists immediately called for Texas to secede from the union. This echoed a declaration by progressive Vermonters, first made in 2003, to explore ways to opt out of a country that they deemed too reactionary.

A November 9 petition asking the Obama administration to “peacefully grant the state of Texas to withdraw from the United States of America” has garnered nearly 120,000 signatures to become by far the most popular petition on WhiteHouse.gov. Additional secession petitions have come in from the other 49 states, with those from Louisiana, Florida and Georgia amassing more than 30,000 signatories apiece.

One thing is certain: a bloc of Southern states that once were essential to any Democratic majority — from Wilson to Clinton, from the onset of World War I to the defeat of Al Gore in 2000 — is no longer. Texas, Mississippi, North Carolina: The Democrats now can lose every one of these states in a presidential race and still win handily. Obama just did. The “Southern strategy” is gone.

Help keep this reporting possible by making a donation today.

Both parties’ wooing of the Deep South proved enormously beneficial to many states, such as Alabama, that began to split away from the Democrats in the 1970s and today are wholly alienated from the Democratic Party. Alabamans receive $2 in federal spending for every $1 they pay in taxes; this dramatic imbalance is an artifact of a dysfunctional U.S. Electoral College that encouraged the leaders of both major parties to court Southern states.

With the South now politically unhinged from the process of deciding the presidential election, calls for secession are the first evidence of the new panic on the Right. Facing the specter of more liberal Supreme Court justices and a political logic that will slowly extinguish political incentives to deliver federal aid to the Southern states, extremists in the region have resurrected a 19th century strategy. Playing the only political card they have left, they are threatening to exit the nation.

The talk is loudest in Texas chiefly because of the state’s size, national clout and pride of place. Admittedly, the Texas secessionists are loony. The most vocal organization, the Texas Nationalist Movement, states baldly: “The fact of the matter is, that there cannot be a union between those that esteem the principles of Karl Marx over the principles of Thomas Jefferson. Here in Texas, we esteem those principles of Thomas Jefferson — that all political power’s inherent in the people.”

Obama’s cautious liberalism — and his continued embrace of Republican economist Ben Bernanke as Fed chairman and the government’s economic manager, rather than highly esteemed Democratic economists such as Paul Krugman or Jared Bernstein — makes the notion of the president as an agent of Marxism cartoonishly ridiculous. Yet when the secessionists move from broad ideology to specific grievances, their arguments for disunion fall squarely in the tradition of “state’s rights” — arguments that have long found favor in the federal courts and with a shifting segment of the public.

“We’ve got a federal government that treats states like Texas as a cash cow, that has no regard for the sovereignty of the states and really treats us merely like an administrative subdivision of the whims of the federal government,” Daniel Miller, who appears to have risen from nowhere to speak on behalf of the Texas Nationalist Movement, told Fox News.

There’s a sense in which Texas, historically, is a kind of inland empire with a distinct identity and political trajectory. The dissenting Texans are well aware, of course, that Texas was, for nearly 10 years, an independent republic before joining the U.S. in 1846. Yet Miller and his collection of far-Right loonies do not really call for the immediate withdrawal from the union, or even for secession at all. Rather, he asks for the Texas legislature to engage in a variant of political theater. “Ideally what we would like to see is the legislature put it to a non-binding referendum,” he told Fox’s Sean Hannity, “so the people of Texas could express their will on this issue.”

Politics as theater is familiar, and the Texas elite is taking the secessionists in stride. The state is home to 26 million people, after all, so even 120,000 signatures in favor of anything can be dismissed as statistical “noise.”

“This is not a real secessionist movement,” Mark Jones, a professor of political science at Rice University in Houston, told Voice of America. “You don’t have any serious political actor getting behind the movement to secede.”

Indeed, the Texas Republican elite, from Gov. Rick Perry on down, has shunned the movement. But in an America dominated by what the historian Daniel Boorstin once called “pseudo-events” — an America where the “fake news” of Jon Stewart can be truer and more believable than the real news of Scott Pelley — a “fake secessionist movement” can take on the trappings of reality, and perhaps already has.

Global possibilities

Look abroad in order to see just how plausible secession is. In the United States, talk of political disunion is associated with insanity. Not so in many other parts of the world. Scots, who like Texans can imagine a bygone past of political independence, may well choose to split from Britain in a vote planned for 2014. In Catalonia, Spain’s wealthiest region and home to Barcelona, Catalans openly debate whether it should engineer a similar split. Galicians have similar aspirations for their northwestern region of Spain.

The existence of the European Union, which provides an umbrella of political services to small nations, enhances the attractiveness of regional splits. In 2010, the EU Parliament called on its member states to recognize the sovereignty of tiny Kosovo, formerly the southern region of Serbia — and 22 EU nations have done so. The movement for political independence has many mothers, and one of them, paradoxically, is globalization, because “shared sovereignty” — especially in the domains of defense, trade and monetary policy — brings concrete benefits.

For the past 20 years the peoples of the world have experienced an unprecedented wave of breakups, driving the creation of smaller political units that possess something like full sovereignty. The collapse of the Soviet Union led to the creation of 15 nations, and when the Soviets released their grip on Eastern Europe, secessionists cheered. Yugoslavia alone gave birth to six different countries. Few of these new states have re-amalgamated. East Germany’s choice of absorption into its larger Western brother proved the exception, rather than the rule.

Successive U.S. governments have welcomed secession abroad, finding easy justifications in the philosophy of Thomas Jefferson, who embraced self-determination with a fervor usually limited to religious belief. Jefferson’s famous dictum, “every generation needs a new revolution,” provides a comfortable berth for secessionists in need of a justification.

In its foreign policies, the United States usually tries first to sustain existing political borders, but quite often will explicitly support new political arrangements from greater sub-national autonomy to outright secession. In the case of Sudan, both the Bush and Obama administrations pushed to separate North from South. While the birth of South Sudan has proved a disappointment, largely because of rampant corruption by the new government, the split has been achieved without massive amounts of bloodshed.

Any nation, so conceived…

Double standards are a staple of U.S. politics, so the openness of presidents past and present to international secessionist movements should not be misunderstood. Abraham Lincoln made his historical reputation by standing up for the American union no matter the cost, which proved to be the Civil War. Given the Lincoln legacy, no American president will easily release any part of these United States from its federal obligations. These commitments of course include a share of the national debt as well as resources. The federal government owns, or controls, a great deal of land, especially in the West, and also shoulders about $50,000 in debt for every living citizen. How these assets — and debts — would be apportioned would be one of the major issues of negotiation in any political separation.

Of course, negotiations sometimes fail. History is strewn with painful civil wars fought over secession. Bitterly contested and sometimes replete with tragedy, violent secessions darken the landscape for the entire enterprise. As Chinua Achebe writes in his new memoir, There Was A Country, the failed secession of the Igbo of Biafra (from Nigeria) led to a savage war from 1967 to 1970 that was filled with “struggle and suffering,” which resulted in uncountable deaths, some by starvation.

And yet: The dream lives on, buttressed by a simple reckoning. If political communities are “imagined communities,” to invoke the title of the classic treatise by the political theorist Benedict Anderson, then following the spirit of Jefferson, political communities can be re-imagined, re-engineered and reborn. The logic of self-determination is not so easily contained by appeals to nationalist pride or historical inevitability. Free association is a powerful engine to achieve effective scale. Yet the same energy can fuel deconstruction of the body politic. E pluribus unum can be stood on its head: ex uno plures (out of one, many).

American fissures

In the United States as elsewhere, the difficulty of secession is not in the calculations: Sundering substates from a larger nation can be engineered with the help of an accomplished accountant. Cleaving Texas or California or Vermont or the Upper Great Lakes, say, from the rest of the United States (all of which have been proposed) would not require special arithmetic dexterity. Obligations to inherit federal debt, and perhaps to indemnify the national government against losses of Texan or Californian lands and resources, could be calculated and contractually expressed.

The trouble is that the American sensibility is so fractious, and our society so diverse, that the neat exit of a single state or states is the most highly improbable outcome in the entire secessionist scenario. On a state level, halting the process of splitting would likely prove impossible, as evidence already indicates. In Texas, co-evolving with the push to explore splitting from the United States, is a movement in Austin, the state’s capital, to secede from Texas itself. Similarly, in Pima County, Ariz., a movement is incubating to withdraw from conservative Arizona and petition to remain in the union.

Individual states, should they withdraw roughly around the same time, might form their own imperfect union, or they might appeal to join other countries. Britain might wish to reduce the sting of having lost Scotland by, say, inviting Texas to become part of its nation-state.

Such possibilities are literally endless because, on the ground, the fissures and centrifugal forces in American life are nearly infinite. Just as the Communist Party officially endorsed the creation of a single state for African Americans in the 1930s, might not gays and lesbians seek their own state? Could not bicycle enthusiasts, eager to smite global warming through the refusal to drive automobiles, welcome their own territory? And of course, the rise of religious polities would be unstoppable. The Baptists could have a state. The Catholics. The Mormons — wait, they already have one. And on and on.

Arise ye secessionists of the earth!

The Right does not have a monopoly on secessionist spirit. Enthusiasm for quixotic campaigns around the independence of states or regions has long fascinated progressives, an enthusiasm animated by a straightforward “small is beautiful” perspective. Just as cities can become bastions of reform and even instruments of liberation, compact smaller nation-states, by virtue of their size alone, can afford to embrace aspects of direct democracy and participatory deliberation that routinely elude large nations. This secessionist impulse often captivates progressives during periods of national retrenchment, such as the 1980s Reagan presidency and the dark years of George W. Bush. When achieving national power seems a forlorn hope, understandably the idea of new political arrangements, which would allow the Left to mount experiments without the impediment of conservative interests, ignites enthusiasm.

However, expediency does not entirely explain the Left’s openness to secessionist ideas and to the revolutionary impulse full stop. There have always been progressives who saw in the very size and scale of the United States the sources of its awesome military and destructive might. By literally downsizing the “Pentagon of power,” to paraphrase the cultural critic Lewis Mumford, the U.S. capacity to do harm in the world would be reduced. For some resisters of total militarization of U.S. life — from the President and assassin-in-chief to the special domestic programs for military veterans only — the sharpest blow struck for peace would be to dismantle the political structure of the United States.

The fantasy of disunion does hold out the possibility of a progressive, social democratic and peace-mongering nation-state — a political destination long sought by the Left. In Ernest Callenbach’s visionary 1975 novel, Ecotopia, this sort of wishful alternative reality is laid out in its full glory. In clunky prose, Callenbach creates a speculative world centered around the political independence of the North- west — an area that today covers the coastal parts of three states, California, Oregon and Washington. The country of Ecotopia resembles Holland in its respect for social freedom; Switzerland in avoiding foreign-policy entanglements; and Germany in its embrace of an environmentally aware, Protestant lifestyle.

In the novel, a journalist from what remains of the United States visits Ecotopia 20 years after secession “not so much to oppose Ecotopia as to understand it.” The narrator, “an international affairs reporter” named William Weston, concludes, after a six-week reporting trip, that “the risky social experiments undertaken here have worked on a biological level.”

Weston continued: “Ecotopian air and water are everywhere crystal clear. … Food is plentiful, wholesome and recognizable. All life-systems are operating on a stable-state basis, and can go on doing so indefinitely. The health and general well-being of the people are undeniable.”

But the narrator, who is after all a citizen of the United States, admits that realizing green dreams has come at an enormous cost in material living standards.“Consumption [is] markedly below ours [in the United States] to a degree that would never be tolerated by Americans generally,” he writes. Yet the very survival of Ecotopia lends credence to an argument that “the era of great nation-states” is fading away and that “separatism is desirable on ecological as well as cultural grounds.”

In his emphasis on the role of identity and culture in shaping political arrangements that aim to promote environmental sustainability, Callenbach prefigures the Pacific Northwestern movement to form the “bio-diverse” nation-state of Cascadia, as well as the proto-secessionist movement in Vermont. That state, which consistently delivers the only radical voices in Congress, still yearns for political expressions rendered impossible even under the most liberal interpretations of states’ rights.

In the Burlington Declaration of 2006, supporters of the Second Vermont Republic insisted on the right to peaceful secession and the centrality of “direct democracy” in political decision-making. Echoing Jefferson and citing the principle of self-determination, the signatories avowed that “it is the right of the people in democratic fashion to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

And the Third Statewide Convention on Vermont Self-Determination, which was held on Sept. 14, 2012, in the Vermont State House in Montpelier, featured the presentation of the Montpelier Manifesto, which was co-authored by (among others) neo-Luddite thinker Kirkpatrick Sale and novelist Carolyn Chute, author of The Beans of Egypt, Maine.

The manifesto frames itself with this opening:

We, citizens of this American land, haunted by the nihilism of separation, meaninglessness, and powerlessness, subsumed by political elites who use corporate, state, and military power to manipulate our lives, pawns of a global system of dominance and deceit in which transnational megacompanies and big government control us through money, markets, and media, sapping our political will, civil liberties, collective memory, traditional cultures, sustainability, and independence, and as victims of affluenza, technomania, cybermania, globalism, and imperialism …

It concludes with this call to action:

Citizens, lend your name to this manifesto and join in the honorable task of rejecting the immoral, corrupt, decaying, dying, failing American Empire and seeking its rapid and peaceful dissolution before it takes us all down with it.

Insurgents on the Right and the Left are more than dimly aware that their particular secessionist stirrings share the same root, if very different fruits. For the polar extremes of the political spectrum, the overwhelming unlikelihood of anyone seceding from anywhere, right or left, North or South, does not render the conversation about secession silly or irrelevant.

Through such speculation, Americans of all persuasions remind themselves that they associate through their own volition, and that their political arrangements, however durable, are not immutable. In short, conversations about secession, however fantastic and fanciful, raise important doubts about fatalistic presumptions and highlight a hidden, but not absent, existential aspect of the American nation-state: that union is no less a choice than disunion.

This insight, however mocked by realists, carries important implications for the distinctive brand of American federalism. By allowing such diversity in laws and government practices between individual states — and even within states, based on differences between cities and counties — the American federal system can be enriched by discourse about secessionist dreams.

The “genius” of asymmetric federalism means, in practice, on the ground, that there is no single American experience, but that Americans, individually and in politically constituted bodies, can revise and invent new political arrangements that respond to changing desires and needs. In theory, there are always higher powers — the Supreme Court, the President, the Congress— that can trump sub-national politics. And then there are domains, such as war and diplomacy, where pressure is great, if not overwhelming, for Americans to “speak” with a single voice. Yet these domains are the exceptions, not the rule. The forces of secession are never wholly dormant in the U.S. political culture because the traditions of asymmetric federalism — one state doing something completely different in a public domain than another — are so rock-solid that Americans take for granted high levels of diversity in their laws, public policies and their forms of government administrations.

That Colorado can legalize marijuana, while Arizona can forge its own limited immigration policy, doesn’t immunize either state from pushing the boundaries of sovereignty even further. By tolerating, even encouraging, different states to take radically different approaches to the public sphere, the United States makes secessionism less toxic to the public conversation. Yet the very permissiveness and promiscousness of American political practice that makes secession easier to imagine may make it all but impossible to enact. In the unitary nation-state of Britain, with its single national police force, taxations rules and the rest, the exit of Scotland would mean an extraordinary set of changes. Not so for the Texans or the Vermonters who already exert, by the standards of European nation-states (if not the entire world) an unusually large amount of control over their affairs.

Hence, the paradox: Does the experience of self-determination make a body politic hunger for more, or less?