Warnings from First Americans: Insidious Changes Are Underway that Will Affect Us All

Stephanie Woodard

The worst mass shooting in recent years. Escalating threats of nuclear war. Catastrophic hurricanes. Calamities and fear rock the nation these days. Meanwhile, public servants are chartering private jets, and the president’s frenzied tweetstorms create yet more chaos and division. As the tweeter-in-chief seeks sycophantic praise (or anything to divert our attention from Robert Mueller’s accelerating investigation), serious policy changes have been proposed, or are underway, in numerous aspects of American life.

For an update, Rural America In These Times spoke to Native Americans — people whose survival requires being extremely well informed about what all branches of the federal government are up to. From their vantage point as sovereign entities with direct government-to-government relationships with the United States, the tribes have a unique perspective on issues including voting rights, the economy, the extractive industries’ hold over this administration and more.

In each case below, they explain how powerfully and comprehensively this administration’s misguided policies would impinge on each and every one of us. After all, “everything is connected,” as Timbisha Shoshone Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Barbara Durham puts it.

Fire on the mountain

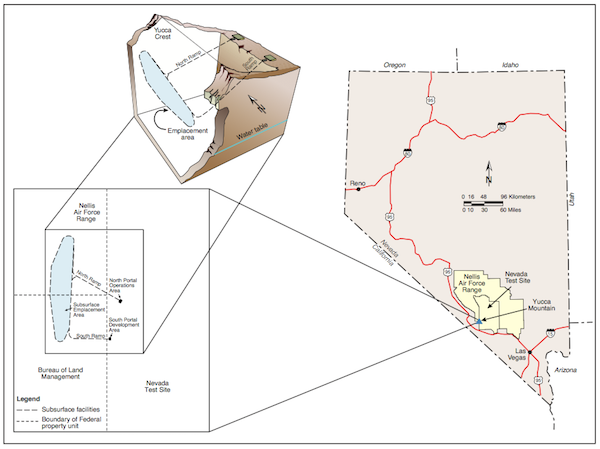

Kim Jong-un can relax! We have already nuked ourselves and are looking into a great way to poison ourselves even more with radioactive waste. In June, Department of Energy (DOE) Secretary Rick Perry suggested using the Nevada National Security Site, aka the Nevada Test Site, as an interim waste dump and at the same time reopening licensing procedures for nearby Yucca Mountain. Under Perry’s plan, the mountain, revered as a sacred site by area tribes, would eventually become the permanent repository for spent nuclear fuel and other radioactive material.

The waste would travel via roads and railroads through communities throughout the country as it made its way to Nevada. Once it arrived, its home would be deep inside the earthquake-prone mountain. The DOE’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the project admits that Yucca Mountain may be shaken by “ground motion” and that “beyond-the-design” events could collapse the waste facility.

The Department of Energy’s proposed radioactive material repository at Yucca Mountain. (Infographic: energy.gov)

The Timbisha Shoshone government blasted the Perry proposal, citing the groundwater contamination that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has said will likely occur, even without earthquakes. Timbisha Chairman George Gholson told the Department of Energy the project “affronts the Timbisha’s way of life, is disrespectful to cultural beliefs, and constitutes an environmental justice infringement on the rights of a sovereign nation. Effects on public health and sacred sites have not been properly studied, Gholson says, pointing out that his people have lived in the vicinity of the mountain since long before the United States existed. Native activists, notably Tom Goldtooth from Indigenous Environmental Network, also excoriated the idea, along with Nevada’s state officials and Congressional delegation.

The Timbisha Shoshone live west of the mountain and test site and still feel the effects of the hundreds of detonations that occurred there, the first of which happened in 1951. According to Durham, radiation has become part of large areas of land and water, redistributed via forces such as the winds, the aquifers and the transpiration cycle. As a result of existing contamination, tribal members in certain areas are reluctant to hunt and collect pine nuts, both staples of the traditional diet, says Johnny Bob, medicine man and traditional chief from the Yomba Shoshone, who live east of the mountain.

Yomba Shoshone medicine man and traditional chief Johnny Bob collecting pine nuts, a staple of the heritage Shoshone diet, in the Nevada mountains in the fall of 2016. (Image: Joseph Zummo)

The United States faces one more very large barrier at Yucca Mountain, adds Bob. In 1863, Shoshone tribal heads and United States representatives signed the Treaty of Ruby Valley, which declared friendship between the parties and guaranteed the tribes a homeland that encompasses most of Nevada and massive chunks of Idaho, Oregon, California and Utah. The federal government seemed to forget all about the agreement for decades, though of course there were distractions — the Civil War, Lincoln’s assassination, the Sioux defending their homelands and more. After the United States woke up to the gigantic gap in the national map, it tried unsuccessfully for decades to pay off the Shoshone tribes.

“We respect the treaty,” says Bob. “And we don’t want the nuclear waste.”

DOE offers one bright spot in all the controversy: According to the FEIS, Yucca Mountain is “highly unlikely” to erupt as a volcano.

This land is whose land?

The Trump administration is trying to shovel vast and pristine portions of the United States into the maw of the extractive industries, such as mining concerns and fossil-fuel companies.

An attempt to cut back the size of national monuments including Bears Ears, a Utah monument replete with tribal sacred sites, in order to allow oil and gas drilling has garnered much publicity and the threat of a tribal lawsuit. The reversal of Obama-era prohibitions against oil drilling in the Arctic and Atlantic seas has already been challenged by a lawsuit by the Center for Biological Diversity, the Native organization REDOIL (Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands) and additional conservation groups.

A Puebloan granary within the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. (Image. blm.gov)

Also in the administration’s crosshairs is Bristol Bay, an expanse of Alaskan land and water that supports a $1.5-billion salmon fishery. The bay underpins the subsistence lifeways of surrounding tribes while providing some 14,000 jobs and pumping associated spending and taxes into the state and national economies.

In 2014, after years of scientific study and public comment on a proposed copper, gold and molybdenum mining operation for the watershed of the bay, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that Pebble Mine would devastate the area. Fast forward to May of this year. Within hours of meeting with Pebble Mine owners, according to a CNN report, the Trump EPA suggested withdrawing Clean Water Act restrictions on the mine and opened a public-comment period on the concept. Administrator Scott Pruitt said the EPA did not seek “a particular outcome” for this turnaround but wished to be “fair” to the mine.

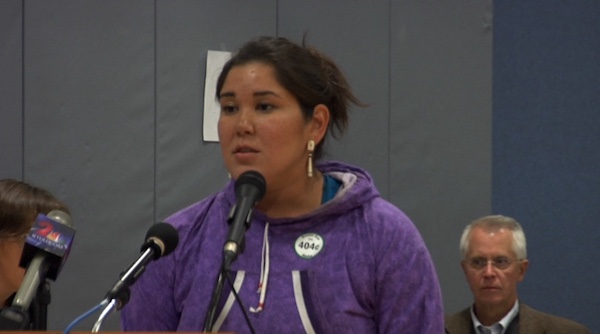

The agency and the mine face fierce opposition in Alaska that cuts across all ethnicities and relationships to the water, says Alannah Hurley, the Yup’ik executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, which represents 14 tribes. Commercial and sport fishermen have joined indigenous people as they rallied, petitioned and spoke out against the mine. During the national election in 2014, two-thirds of Alaskans voted to create barriers to the opening of Pebble Mine. The opposition won in every precinct in the state.

Sockeye salmon in Bristol Bay. (Image: epa.gov)

“Nothing has changed about the project and the objections to it. The only change is the political leadership of this country,” says Hurley. “This administration puts profits before human beings and before science. It is willing to create a humanitarian, environmental and economic crisis in Alaska so that a mining company can reap profits. If the administration succeeds, a huge sustainable resource will be destroyed.”

These days, Hurley is traveling around Bristol Bay, letting isolated communities know what is going on so they have the information they need to submit comments to the EPA. “We want to make sure our voices are heard,” says Hurley.

Robin Samuelson, a Curyung tribal member and president of Bristol Bay Economic Development Corporation, has vowed to fight the mine to his last breath. At that point, he says, his grandchildren will take up the cause: “And their kids are going to fight Pebble. We and Bristol Bay will never give up.”

Alannah Hurley, the executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, opposes the Pebble Mine at an EPA hearing back in 2014. (Image: savebristolbay.org)

Locked and leaded

On Ryan Zinke’s first day as Secretary of the Interior, he rode to work on a horse and signed an order. The document rescinded restrictions on use of lead-based ammunition and fishing-line sinkers while on lands managed by the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). “An attack on our hunting heritage” was how the NRA described the Obama-era restrictions, which would have phased out these uses of the toxin on FWS lands by 2022.

Though the nation has long banned lead in paint, water pipes and gasoline, hunters and fishermen still pump startling amounts of it into the ecosystem and food chain, according to the Center for Biological Diversity. “In the United States, an estimated 3,000 tons of lead are shot into the environment by hunting every year, another 80,000 tons are released at shooting ranges, and 4,000 tons are lost in ponds and streams as fishing lures and sinkers — while as many as 20 million birds and other animals die each year from subsequent lead poisoning,” the Center says.

An X-ray reveals a .22 caliber lead bullet lodged in a California condor’s stomach, confirming suspicions that it died from lead poisoning. (Image: ventanaws.org)

Tribes try to salve the wounds. At the Zuni Pueblo eagle sanctuary in the New Mexico desert, some of the birds cared for there have lead-related nervous-system damage. This is the result of consuming the carcasses of animals that have been shot with lead pellets, or of being shot themselves. In August 2017, the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, in South Dakota, celebrated the release into the wild of an eagle that a zoo had rehabilitated with the help of lead-testing equipment donated by the tribe.

Humans are at risk as well. When hunters, fishermen and their families eat game shot with lead-based ammunition or consume fish taken from contaminated waters, the toxin is on the menu. “[Lead] can degrade a person’s vascular, renal, nervous and reproductive systems,” with children especially vulnerable to the effects, say wildlife biologists at the Yurok Tribe. They say the heavy metal can’t be entirely eliminated when cleaning the game, because lead-based bullets explode into fragments as small as a mote of dust when they strike a target.

Yurok community outreach programs have warned of the dangers. A tribal ammunition exchange replaced hunters’ lead-based ammunition with non-lead varieties. The project was a contribution to tribal and state efforts to restore the endangered condor, which, like eagles, are culturally important birds that may be poisoned by consuming contaminated carrion.

What if scientists discover that lead isn’t so bad? the NRA asks in a press release. A group of top scientists found plenty of reasons to scoff at this idea. They called lead “one of the most-well-studied” of poisons, “with toxic effects…in humans and wildlife, even at very low exposure levels.”

In short, with tens of thousands of tons of lead bombarding the environment each year, we all have a shot at lead poisoning.

Ryan Zinke squints into the distance with his shotgun. (Image: DOI.gov)

Equality redefined

It’s not just Russians anymore. Attacks against voting rights are proliferating beyond Putin’s pals hacking into state election systems or manipulating public opinion via social media. With the Trump administration’s all-out assault on ballot-box access, non-Natives are getting a taste of what Native people have long experienced, according to OJ Semans, the Rosebud Sioux executive director of Four Directions, a nonprofit that advocates for equal rights.

“To put it bluntly,” Semans says, “as the Trump administration chips away at the ability to cast a ballot, you non-Natives are becoming as ‘equal’ as we are.”

Among administration efforts, Semans notes, a House of Representatives committee has moved toward defunding the Election Assistance Commission, which helps improve election systems and prevent hacking. Then there’s the Justice Department’s opposition to a federal-court decision that called a Texas voter-ID law discriminatory, along with the department’s scrutiny of the National Voter Registration Act, with an eye toward purging voter rolls.

Ominously, Semans adds, the conservative-dominated Supreme Court will soon take up a case in which a lower court declared that Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled legislature had gerrymandered, or geographically rigged, voting districts to ensure they could keep electing their own. Will the Court’s decision in the case clarify the issue?, Semans asks. Or will it make gerrymandering easier — following its own lead in Shelby v. Holder, which demolished certain portions of the Voting Rights Act, making ballot-box access even more difficult for vulnerable voters, including Native Americans.

OJ Semans, executive director of Four Directions, at a voting rights hearing. (Image: votingrightstoday.org)

NARF attorney Natalie Landreth, who is Chickasaw, rolls her eyes at the idea of the commission run by Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, which seeks to prove voter fraud while vacuuming up voters’ personal data. Landreth called Kobach’s group a “sham” in search of a nonexistent problem. “It’s like setting up a commission to hunt for unicorns,” Landreth wrote in a statement for a September hearing of the Native American Voting Rights Coalition (NAVRC), which Semans chaired in Bismarck, North Dakota. The coalition includes NARF, the National Congress of American Indians, the ACLU and other concerned groups.

And don’t forget the president’s suggestion during the 2016 election that his supporters take it upon themselves to challenge other voters, vigilante-style, in the polling places. “Voter harassment is sometimes physically confrontational, but it doesn’t have to be in order to work,” Semans says. The NAVRC panel heard from Native voters that they frequently face uncooperative poll workers or a gauntlet of unfriendly strangers acting as polling-place observers. “Situations like these can go a long way toward scaring off voters,” Semans says.

When Natives need to register, vote early, get transportation to distant polling places, set up precincts in their own communities, and/or use the ID they are likely to have, like a tribal ID, they get little help from the local governments that administer voting, according to an In These Times investigation. Says Semans, “We also don’t necessarily have the technology for the new voting options — online ballot requests and the like. Any access we have, we got ourselves, through voter-registration drives, get-out-the-vote campaigns and federal lawsuits. We don’t even have money, so all this has been accomplished with donations, volunteers and pro-bono attorneys.”

Advocates have turned to the federal courts to obtain voting rights for Native people. From left, Michaelynn Hawk, Crow; South Dakota rancher Bret Healy and Rosebud Sioux Barb and OJ Semans, all from Four Directions rights group; Mark and Ilo Wandering Medicine, Northern Cheyenne; and Tom Rodgers, Blackfeet, of Carlyle Consulting, seen in Portland, Oregon, ahead of a hearing for Wandering Medicine v. McCulloch. (Image: Joseph Zummo)

In August, Semans served as an election observer in Kenya under the auspices of the Carter Center; he will return to Kenya for the October re-do of the disputed presidential portion of the election. “The Kenyan election amazed me,” Semans says. “I saw a country’s original people involved in running their own elections. We don’t have that in the United States.” He also saw that the Kenyan political-party observers who scrutinized ballots for irregularities worked together to ensure every eligible ballot was counted, no matter for whom it was cast.

“Think back to the Bush – Gore election and the hanging chads in Florida,” Semans says. “In U.S. elections, our goal when scrutinizing ballots is knocking out the opposition’s votes. We put party before country. The Kenyans put country before party.”

Semans says fighting for equal rights is a privilege. “I wake up every morning glad I can do this work. It’s a struggle for equality for us Natives, of course, but for everyone else as well. People of every description have lived in, worked in or married into our Native communities. When we win, everyone wins.”

Stephanie Woodard is an award-winning human-rights reporter and author of American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle for Self-Determination and Inclusion.