On February 3, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) removed thousands of documents pertaining to its enforcement of animal welfare laws from its website. No longer available to the general public, the deleted information includes several years worth of annual inspection reports and agency correspondence that document the mistreatment, abuse and/or death of animals at research facilities, zoos, puppy mills, equestrian exhibitions and other locations.

The USDA released a statement citing privacy concerns as the primary reason for the removal. Animal rights groups, however, say the action purposefully shields from public exposure those profiting from the mistreatment and exploitation of animals.

The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is one of 29 agencies and offices operating within the USDA. In addition to its mission of “improving agricultural productivity and competitiveness and contributing to the national economy,” the agency is responsible for the administration and enforcement of the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) and the Horse Protection Act (HPA).

Signed into law by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966, the AWA regulates the minimal standard of acceptable care and treatment for animals used for research, product testing and public exhibitions (such as circuses). It’s the only federal law of its kind and does not include birds, rats, mice or cold-blooded animals. The law also does not apply to farm animals, which are regulated under the Humane Slaughter Act of 1958.

The HPA was implemented in 1970, four years after the AWA, to end the practice of soring. For those unfamiliar with this illegal (and truly sick) manipulation of horse behavior, here’s how Wikipedia defines it:

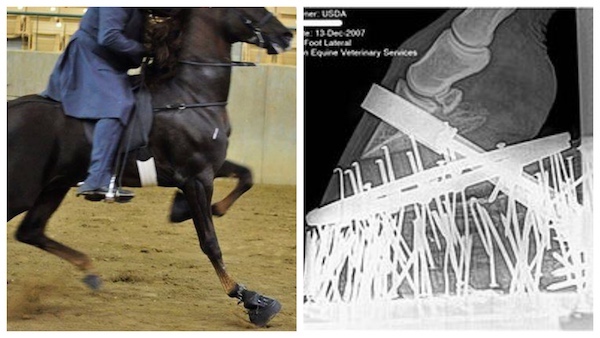

Soring is the practice of applying irritants or blistering agents to the front feet or forelegs of a horse, making it pick its feet up higher in an exaggerated manner that creates the movement or “action” desired in the show ring. Soring is an act of animal cruelty that gives practitioners an unfair advantage over other competitors.

It’s been 47 years since the HPA made soring a punishable crime, but violations persist. In 2012, for example, Jackie McConnell, a top equestrian trainer in Tennessee was secretly caught soring on video and charged with 52 counts of cruelty and ultimately forced to resign in disgrace. In the law’s early days, only official APHIS inspectors were authorized to perform soring inspections but this quickly proved too expensive for the federal government and the HPA was amended in 1976 to allow non-APHIS inspectors — known as designated qualified persons (DQPs) — to become trained and certified in soring detection.

The desired result of soring abuse is an exaggerated gait known as the “Big Lick.” On the right, an X-ray of a Tennessee Walking Horse showing shoe “stacks” — multiple pads nailed to add weight and banded across the hoof — also known as “pressure soring.” Violations of the Horse Protection Act are seen most often in the Tennessee Walking Horse industry, but the HPA covers all breeds. (Photo / Caption: Legal Reader / Wikipedia Commons)

A sudden change

In recent years, the online availability of records pertaining to APHIS inspection and enforcement of the AWA and HPA has provided the general public with important access to the otherwise secretive world of animal testing, breeding and selling. The database also provides journalists and animal rights organizations with an essential resource for researching and publicizing the most egregious industry violations.

As of Friday, however, members of the public attempting to access this portion of the APHIS online database (including, for example, individuals seeking to verify the reputations of dog breeders) are getting redirected to a statement that reads in part:

Based on our commitment to being transparent [sic], remaining responsive to our stakeholders’ informational needs and maintaining the privacy rights of individuals, APHIS is implementing actions to remove documents it posts on APHIS’ website involving the Horse Protection Act (HPA) and the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) that contain personal information. These documents include inspection reports, research facility annual reports, regulatory correspondence (such as official warnings), lists of regulated entities and enforcement records (such as pre-litigation settlement agreements and administrative complaints) that have not received final adjudication.

Over the years, palms have been greased and various loopholes exploited by some businesses to skirt HPA violations, but rigorous USDA-APHIS enforcement of both animal welfare laws has remained a priority. Prior to the Internet, public awareness of industry violations was minimal — and manageable. In the digital age, however, horse industry organizations (HIOs), DQPs and animal-based companies named in the APHIS reports published online have found themselves subjected to public criticism, which is bad for business. In extreme cases, this has escalated into personal threats aimed at business owners by outraged citizens. As a result, companies and individuals whose mistreatment of animals has been hampered by growing public awareness of animal mistreatment have been fighting tooth and nail to scale back government disclosures.

For the moment, these efforts have appeared to pay off. The USDA’s announcement continues:

In addition, APHIS will review and redact, as necessary, the lists of licensees and registrants under the AWA, as well as lists of designated qualified persons (DQPs) licensed by USDA-certified horse industry organizations to ensure personal information is not released to the general public.

Is this a Trump initiative or a coincidence?

As to whether the USDA’s decision to remove the documents are part of the Trump administration’s efforts to make America great again by removing any and all obstacles to profitability…or a coincidental regulatory change that happens to benefit industry, the Washington Post reports:

It is unclear whether the decision to remove the animal-related records was driven by newly hired President Donald Trump administration officials. When asked questions about the change, a USDA-APHIS representative referred back to the department’s statement. The Associated Press reported that a department spokeswoman declined to say whether the removal was temporary or permanent.

But it would not be surprising if the decision was “driven” by President Trump’s arrival. Department of Agriculture policies and regulations often have economic winners and losers, and many animal-related business owners consider themselves on the losing end of Obama-era federal oversight at large. On January 19, the Calvary Group, a trade association that is committed to “protecting and defending animal enterprise,” accused the Obama administration of hiring “animal rights extremists” into key positions at the USDA. They further alleged these employees then released private licensing information “knowing full well” that it would be used to attack the licensee’s business and customers. The statement reads, in part:

Animal rights groups, such as Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) have, in recent years, turned to a disturbing tactic of singling out individual animal owners and animal related businesses by publishing their names, their addresses, private business information, and photographs of their animals and place of business on-line, while falsely manipulating the information with the intent of damaging their business, and discouraging customers and advertisers from continuing their business relationship.

HSUS was responsible for releasing the abovementioned soring video and the accusations fly both ways. PETA was among the first to issue a statement condemning the USDA’s recent action:

This information is crucial to PETA’s work to make sure that the USDA actually does its job. Our dozens of investigations, such as our undercover work at notorious monkey dealer Primate Products, Inc.—where we found monkeys cowering in fear and so neglected that they had frostbite and open, untreated wounds — show that the USDA can’t be trusted to enforce animal-protection laws and regulations. Now, the agency is shielding itself — and the animal exploiters — from scrutiny.

Here’s perhaps something everyone can agree on: Animals deserve respect. The people who profit from their mistreatment are animals (too). But when public awareness becomes bad for a business, that business probably needs to rethink what it’s doing — not lobby the federal government to restrict transparency.