Civil-Rights Complaint Details Horrific—Even Deadly—Discrimination Against Native Kids

Stephanie Woodard

Teachers and coaches in the Wolf Point, Mont., schools have called Native students “dirty Indians” and “rez kids,” performed “war whoops,” told a concerned Native parent “fuck your daughter,” and informed the mother of a special-needs five-year-old that he has to change his behavior if he wants his non-Native classmates to stop biting, hitting and sexually touching him.

A Fort Peck Assiniboine and Sioux Nations’ discrimination complaint claims all this and more is par for the course for tribal children in the Wolf Point School District. On June 28, the tribes submitted the complaint to the U.S. Departments of Justice and Education under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The act prohibits discrimination based on race, color or national origin in federally funded programs, including local school systems. Attorney Melina Healey, a fellow with the advocacy group Equal Justice Works, is representing the tribes, along with additional attorneys. The ACLU of Montana signed on in support of the complaint.

“We are at a do-or-die moment for our tribe’s children,” says Roxanne Gourneau, a Fort Peck tribal executive board member. “I don’t want any more of our youngsters to end up in the cemetery or prison.”

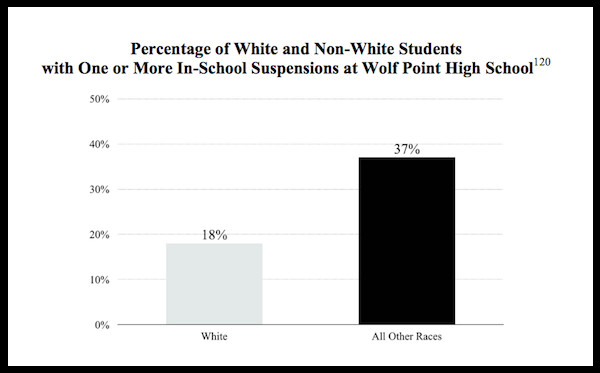

The complaint asks the federal government to help bring the Wolf Point School District into compliance with federal law; it is not a lawsuit and does not request compensation. It does provide the federal agencies with many personal narratives and much data to support its allegations that Native kids are subjected to staff and student bullying, and are excessively disciplined, receiving a disproportionately high rate of suspensions and expulsions. The complaint maintains that Native students are discouraged from taking advanced academic courses for which teachers control enrollment; instead, they are more likely to be warehoused in an underfunded alternative school.

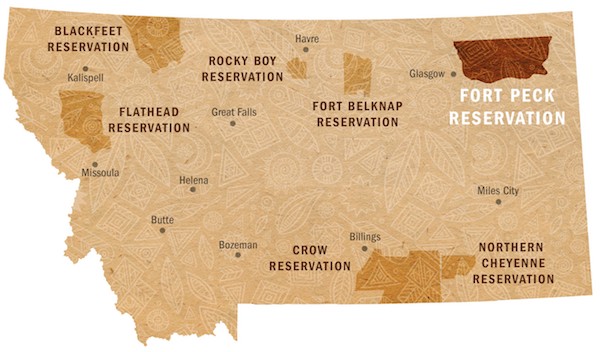

Wolf Point, also the county seat of Roosevelt County, Mont., is the largest community on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. (Image: montana.edu)

The Wolf Point schools’ student population is about 64 percent Native, drawn from the surrounding Fort Peck Indian Reservation, in northeastern Montana. However, whites dominate the town’s political and economic life, and hold most of the jobs at the school. As a result, there are few Native teachers and coaches on staff to serve as mentors and role models. As a consequence of all this, according to the 46-page complaint, Native children do not receive the equal education that the law requires.

The federal agencies have 180 days to decide whether they’ll investigate.

A portion of the Wolf Point School District’s suspension data as mentioned in the tribes’ complaint. According to the District’s 2013 online report card, 72 students total received at least one in-school suspension: nine were white, 32 were Native American, 18 were “Two or More Races,” and 13 were Hispanic. Total enrollment that year was 219. (To read the complaint in its entirety click here: aclumontana.org)

“Something is very, very wrong at Wolf Point.”

In 2010, Gourneau says, her son, Dalton, paid a terrible price for the school district’s disciplinary policies. After being kicked off the wrestling team just before a big tournament, Dalton tried to plead his case with Wolf Point High School officials. When this proved unsuccessful, the well-liked senior wandered the school’s corridors for a while, walked home and shot himself. He was 17.

“I am terrified that my grandchildren will be next,” Gourneau says.

Attorney Jeana Lervick, of the district’s law firm, Felt, Martin, Frazier & Weldon, wrote in an email to Rural America In These Times, “I’m sure you can appreciate that the District is interested in a thorough, in-depth look at every aspect of concern. Therefore, the District’s only statement at this time is that it is deeply concerned by the allegations, is committed to the wellbeing of all students and staff, and is carefully reviewing the document at this time.”

Roxanne Gourneau, a grandmother and Fort Peck tribal executive board member. (Image courtesy of Roxanne Gourneau)

Wolf Point’s list of vision statements introducing its 2013 – 2014 online report card for state school districts offers a positive perspective on the education that Wolf Point offers. The list reads, in part: “All children feel safe, welcome, and successful,” and “All school personnel are respectful, tolerant of differences, consistent, and nurturing.”

The online report card also shows a graduation rate that, at 70 percent, is more than 10 percent below the Montana state average. Meanwhile, none of the elementary, junior high and secondary schools that make up the Wolf Point district achieved “adequate yearly progress” in reading or math proficiency that year.

Life and death

Excessive discipline and a low graduation rate mean that some of Wolf Point’s Native students are likely to acquire criminal records instead of degrees, according to the Fort Peck complaint. Some don’t make it at all. The Fort Peck tribes declared a widely reported suicide emergency during the 2009 – 2010 school year, after 20 attempts and five completions among its children.

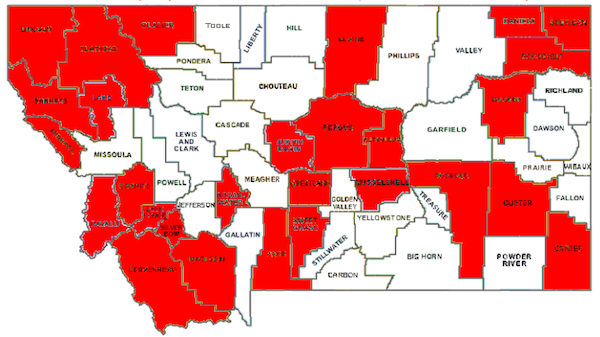

For Fort Peck youth aged 15 – 24, the suicide rate was 82.6 per 100,000 during the decade leading up to 2010, according to the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services. This far exceeds the national rate of 12.93 per 100,000 in 2014 for all ages, sexes, and population groups, according to a Montana Suicide Mortality Review Team report.

Montana counties shaded in red indicate a suicide rate at or above the 90th percentile nationally in 2012. (Source: Montana DPHHS, Montana Vital Statistics)

County-level data for 2015 shows that the crisis has not abated in Roosevelt County, which overlaps Fort Peck; 28 out of a total of 233 high school students attempted suicide at least once that year. In the spring of 2017, one Wolf Point student killed herself; a second was hospitalized after attempting suicide.

Native parents told RAITT that unpunished verbal harassment and beatings by white students, along with violent behavior by teachers — cursing, shouting in students’ faces, striking a Native child from behind with a basketball, smashing a ball against a wall in a manner that children perceived as threatening, and the like — have caused individual Native students as many as several years’ worth of panic attacks, thoughts of suicide and other stress-related responses.

Tribal parents and grandparents told RAITT that each fall they face the first day of school with dread, as they wonder whether their children will survive the academic year ahead. So far, says the Fort Peck complaint, the Wolf Point district has rebuffed the tribes’ offer to collaborate on a suicide-prevention program. Lervick’s did not respond to queries about the district’s reasons for not offering such a program.

The Wolf Point school district has long been regarded as troubled. In 2013, it settled an ACLU lawsuit alleging that gerrymandered school-board voting districts favored white residents of the town and allowed them to control the school and its resources. Though the voting districts were subsequently redrawn, some Native board members now claim that secret board meetings and communications shut them out of decision-making.

A Fort Peck Sioux tribal banner. (Source: fortpecktribes.org)

From 2003 to 2008, the Wolf Point schools were under Department of Education (DOE) monitoring. According to documents obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request and first reported in Indian Country Media Network, this occurred after a three-day community forum that was sponsored by the Fort Peck education department, among others. During the forum, parents shared their children’s experiences and had consultants tour the schools and speak to administrators.

The consultants — Delores Huff, a California State University professor and American Indian-education expert, and journalist Christina Rose — wrote a report that became the basis of a 2003 DOE civil-rights complaint. Huff, who is Cherokee, and Rose found a locked padded room where Native students were detained for even minor offenses, heard parent allegations that the school routinely urged that Native children take the behavior-modification drug Ritalin, irrespective of need or a medical evaluation, and learned that a teacher had slaughtered a litter of kittens in a particularly bloody manner outside a classroom window and within view of terrified children.

The two consultants told DOE that they saw little evidence of Native cultural references at Wolf Point, other than a bulletin board touting “Native American Role Models,” almost all of whom were light-skinned and/or blond. Native children learn that “they don’t belong,” they wrote in their report.

Huff and Rose also learned of one child who died and another who sustained head injuries while playing on playground equipment that remained in use at the time of their visit. The inordinately high mortality among Fort Peck youngsters, including those who are students at Wolf Point, has not only been documented by Huff and Rose and by Montana state suicide reports. It has also been documented in the current DOE/DOJ complaint, in a 2011 U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing, and in numerous media accounts over the years.

District administrators offered explanations that Huff and Rose conveyed in their report: Among them, the padded room (now closed) was constructed “to code,” an apparent reference to building codes, and the teacher who killed the kittens was suspended for a few days. Bottom line, they wrote, “Something is very, very wrong at Wolf Point.”

DOE began monitoring the district with continual inspections until it felt, in 2008, that the Wolf Point schools had improved enough to remove oversight.

Difficult (and distant) choices

Some Wolf Point families transfer tribal children to schools in predominantly Native areas of the reservation. However, this can be cumbersome and expensive for poor working folk, observes grandparent and tribal member Louella Contreras. One of the closest public school systems, in Poplar, Mont., is 20 miles from Wolf Point. Assuming a parent has the time, vehicle, gas money, ability to get off work and/or access to a babysitter, that means two daily round trips, adding up to 80 miles on the road each school day, Contreras says.

One parent decided this was her best option. Worried about her daughter’s depression as a result of her treatment by staff and students at Wolf Point, the mother transferred the girl to the Poplar school system. “Everyone welcomed us with open arms,” says the mother, who wishes to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation in Wolf Point. “And really important, in Poplar’s culture classes, my daughter is learning good things about her heritage instead of feeling that everything about her and her people is bad.”

Still, says Contreras, Native families shouldn’t have to go through this. She points out that the Fort Peck reservation is the tribal students’ traditional homeland, and for those who live in Wolf Point, it is their hometown. “How can the school continue to give our children the impression, or actually tell them, that they don’t belong?” she asks.

There are “Native American” classes at Wolf Point these days, Contreras adds. “But they’re taught by a white woman. She may be a fine teacher, but what can she really know of the meaning of anything she tells our children about?”

Contreras reiterates a point that other parents made, which is that solving these problems is literally, not figuratively, a matter of life and death for Fort Peck’s children.

Power plays

Attorney Melina Healey first visited Fort Peck and Wolf Point several years ago in the course of research that resulted in a work of legal scholarship, “The School-to-Prison Pipeline Tragedy on Montana’s American Indian Reservations.” In a 2013 interview, Healey told Indian Country Media Network that she was initially surprised to see a white enclave on an American Indian reservation. “Then I realized how much white people benefit from the reservation, including jobs in the schools,” Healey said. “They live in nice houses on top of a hill, while housing for American Indians is very different. Looking further, I saw how prominent school is in Fort Peck children’s lives and why expulsions and other disciplinary measures, applied unfairly, are devastating.”

Equal Justice Works fellow, attorney Melina Healey. (Photo: Wyckoff-Tweedie Photography)

How did white incomers end up in control of Wolf Point’s economy, political system and schools? This takeover followed the allotment, or breakup, of the Fort Peck reservation. In a process described by an In These Times special investigation, the U.S. government divided many communally held Indian reservations into separate, individually owned plots, or “allotments.” This occurred during the 1800s and early 1900s. The government awarded some tracts to tribal members and sold the rest to white settlers.

The practice was intended to weaken the tribes and their economic and social structures, according to President Teddy Roosevelt. He called it “a mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass” in a 1901 message to Congress. And it worked. Partitioning the reservations destroyed tribal economies, which had relied on collective, seasonal, rotating use of large tracts of land. The federally driven extermination of the great buffalo herds was another blow to the foodways of the Sioux, Assiniboine and other tribes for which the animals were a dietary staple.

The Fort Peck Indian Reservation, circa 1920. (Image: makeitright.org)

The Wolf Point town website says the burg was little more than a few settlers and a railroad station until 1914:

“Only one more thing was needed. Wolf Point was on an Indian reservation — a huge reservation with very few Indians. [Then] the date everyone was waiting for arrived — the official opening of the Fort Peck Reservation to homesteading. June 30th was the big day, and there were long lines at the Federal Land Office.”

Whites got the best cropland, according to the current Fort Peck complaint, setting the pattern for their future economic dominance of the area.

Hopes for the future

“This is not an adversarial process,” Healey says of the Fort Peck tribes’ complaint. “The tribes want the federal government to facilitate a town-tribe reconciliation, while fulfilling the government’s legal responsibilities to Native people as their trustee. At the end of the day, what tribal members want is for their children to be treated equally and fairly and to feel safe in school.”

Gourneau says the complaint is directed toward a system, not individuals. “A good many teachers and administrators who were around during the 2013 ACLU lawsuit have left,” she told RAITT. “Those who replaced them, even those who came here from out of state, soon began engaging in the same bullying and excessive discipline of our Native children. It was like iron filings to a magnet. I was amazed and realized the problems are systemic.”

The problems aren’t only at Fort Peck, though, says Gourneau. “Reservations all over the country face education-related discrimination, whether their children attend schools in white bordertowns or in white on-reservation enclaves. I hope Fort Peck’s complaint becomes the key that opens up this issue and gets it resolved nationwide.”

Fort Peck youth, like this young woman in traditional dress, maintain their time-honored tribal heritage. (Image courtesy of Ruth Jackson)

Stephanie Woodard is an award-winning human-rights reporter and author of American Apartheid: The Native American Struggle for Self-Determination and Inclusion.