Page Not Found

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

|

||

Page Not Found

Understanding Arafat

Is Yasser a man of peace?

A True Friend of Israel

Abuse Inside the Razor Wire

A prison murder shocks Florida

Courting Disaster.

Appall-o-Meter

History We Can Use

BOOKS: Why you can thank radical leftists for democracy.

BOOKS: Life, liberty and the pursuit of enhanced DNA.

BOOKS: The sex lives of kids.

City on Fire

BOOKS: The Cold War and the architecture of survival.

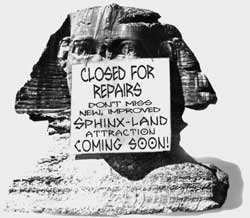

BOOKS: Excavating The Future of the Past.

Rising neofascism in France.

Activists targeted as ‘terrorists.’

Smart ALEC

A little-publicized group wields corporate power.

Girl Power

Women Win Big in Costa Rica

In Person: Alexandra Pelosi

|

May 9, 2002

Out with the Old

His new book, The Future of the Past, collects a dozen of his pieces from recent years, most of them published in The New Yorker. It’s the kind of book well-intentioned editors put together all the time: a loosely-themed collection that doesn’t quite live up to its flap-copy aspirations but serves as fodder for endless barroom arguments and breakfast table debates. In most of the essays, Stille hitches along with an articulate and passionate researcher of one stripe or another—an Italian anthropologist in Papua New Guinea, an American primatologist in Madagascar, a French archeologist in Egypt—in an effort to examine the ways technology affects societies in transformation, and seeking throughout to capture “the complexity, strangeness and contradictions of transformation” itself. Stille tends to champion the passion and curiosity of the researchers he follows, even as he reveals their extraordinary blend of dedication and arrogance. Upon being introduced to Stille, the expert on non-mechanized pond systems of sewage treatment in India apologizes for more-or-less deliberately ignoring his name: “For every new person’s name I learn, I forget the name of an algae.” The primatologist in Madagascar, heading off into the bush in search of a mysterious forest denizen, declares that “it’s probably nothing, but if I find it I’ll be on the cover of Science magazine for sure!”

A second theme that emerges is the fact that even in cases where the past is recovered or preserved, cultural norms regarding the past are comically relative. In China, scores of sculptors produce modern replicas of the legions of miniature terra-cotta warriors that ancient emperors entombed with them, and then lend them to Western museums as authentic relics. If you’ve seen an exhibit of these miniature armies in recent years, chances are you’ve seen fakes. In India, efforts to rid the Ganges of fecal matter (so bathers can perform ritual ablutions safely) while remaining true to its sanctity in Hindu doctrine have resulted in hopelessly mis-guided uses of Western-style sewage treatments; the government “adopted a European technology that was designed more to protect fish than to protect people,” leaving Ganges bathers no better protected. And in Japan, Stille points out the example of the Shinto temple “originally built in the seventh century A.D. [that] is ritually destroyed every twenty years. The Japanese think of it as being 1,300 years old, yet no single piece of it is more than two decades old.” But the broadest question Stille raises is whether more information necessarily leads to more knowledge. “Will a wired world,” he asks, “be better informed than any other, or will information crowd out knowledge as we struggle to sort through the flood of messages and images with which we are bombarded each day?” On this score, Stille’s best piece is “The Museum of Obsolete Technology,” a provocative account of the speed with which U.S. repositories of government documents are filling up. In 1994, he reports, the National Archives and Record Administration opened a new storage facility intended to last several decades. But despite the fact that it is “the third-largest government building and about half the size of the Pentagon, [it] is already approaching its storage capacity [and] the space for paper records ... is expected to run out by 2003.” At issue is not just lack of space, but the very principles of collection and preservation of historical memory. The risk is of “such a vast accumulation of records that the job of distinguishing the essential from the ephemeral becomes more and more difficult.” What he calls the “double-edged nature of technological change” is partially to blame. Just as increasing restoration work dooms some antiquities, the dizzying rate at which electronic hardware has progressed has made older systems obsolete in record time, leaving many records potentially unreadable. “One of the great ironies of the information age,” writes Stille in one of his most satisfying insights, “is that while the late twentieth century will undoubtedly have recorded more data than any other period in history, it will also almost certainly have lost more information than any previous era.”

Here is the iconic defender of the past, striving to save the nearly extinct artifact of a long-dead age. But Foster is no sentimental simp, and Stille brings out a striking paradox in Foster’s view of the past. In the course of his teaching, he creates widely admired, labor-intensive worksheets that his students implore him to save for future generations by having them published. But he steadfastly refuses, and instead “he destroys his elaborately constructed worksheets so that he has to reinvent his course every year, making each course new and unique.” It is Foster’s story that Stille claims “first suggested the idea for this book,” and though he doesn’t draw together the implications of Foster’s final act of anti-historicism, it seems to me to offer a vital lesson: amid a modern culture increasingly amnesiac and yet heritage-mad, the messiness of human agency is all we have, and the right path is a kind of historical memory that embraces neither the flush of the collector nor the gush of the nostalgist. The collector’s will to save everything is, after all, an exercise in futility, especially in a society increasingly tight on space and unwilling to pay the storage costs. But more importantly, it is an exercise in folly; however noble the sentiment, it is the kind of insipid thinking behind Internet chatrooms and high-school yearbooks, and that way lies only the dopier strands of preservationist mania, droopy VH-1 Behind the Music specials, and the false moral equivalences that end up equating a suffragette’s shoes with her speeches. Against this tide Foster represents the willingness to revise, to edit and to throw away.

Or as Miles Davis succinctly put it when asked for the secret of his beautifully spare compositions: “I always listen for what I can leave out.” The nostalgist’s easy tears for even the lowliest of lost documents, lost buildings, lost anything is no more worthy. In the natural world, historical loss is nature’s beauty itself; “natural selection” is the elegant if misleading name given to such a process. Thomas Carlyle embodied its stony resolve when in 1835 he lent his drinking pal and intellectual compatriot John Stuart Mill the draft manuscript of his monumental history of the French Revolution—and subsequently discovered (to their mutual horror) that Mill had accidentally left it out where his servant could use it to kindle a fire. Two years of work destroyed in a moment, Carlyle cursed the day—and began to write it again. Return to top of the page. |

|