The answer is: We don’t know.

“The great majority of people convicted of criminal offenses are guilty,” says Samuel Gross, editor of the National Registry of Exonerations and a law professor at the University of Michigan, “but the great majority are not everyone.”

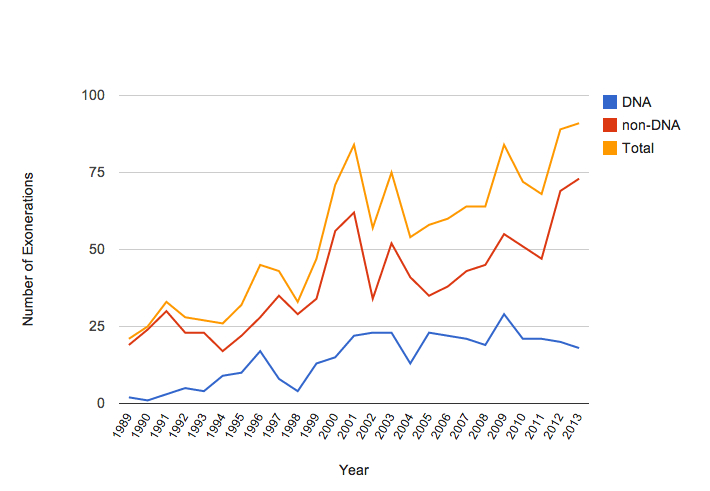

This year the National Registry of Exonerations, the only body tracking exonerations nationally, has already recorded more than 50 cases in which “a person who has been convicted of a crime is officially cleared based on new evidence of innocence.” The interactive list ranges from people in prison for a matter of years to some incarcerated for decades and shows a steady rise in the number of recorded exonerations over the last two decades.

As reported here at The Prison Complex, there have been a string of high-profile exoneration cases this year.

Just last month Michael Phillips took a step towards clearing his name having previously been convicted in the 1990 rape of a 16 year-old girl in Dallas, Texas. His exoneration was highly unusual because it took place as the result of a review by the prosecutor’s office, not because of legal action on Phillips’ behalf. As the Washington Post reports, Phillips even plead guilty to the original crime.

Phillips pleaded guilty because, he said later, his attorney told him that as a black man who had been accused of raping a white teenager, he should try to avoid a jury trial. He went to prison for a dozen years and, after his release, spent another six months in jail after failing to register as a sex offender. Continue reading…

Exonerations can offer a limited insight into the wider issue of wrongful convictions. The National Registry of Exonerations currently lists 1,409 cases. According to Gross his team have got better at tracking the number of exonerations, but he says “the great majority of wrongful convictions never come to light at all. Exonerations are a minority of the people convicted.”

Monitoring the number of exonerations is made more difficult by the fact that much of the data is kept at a county level and rarely come to national attention, with the exception of high profile cases like Phillips. “Some types of false convictions are likely to be underreported,” says Gross “for example false convictions for misdemeanors or low level felonies, almost none of those will result in exonerations and if they do we almost never hear of them.”

That doesn’t mean that it’s impossible to identify trends in exonerations. “We can see in particular some very strong patterns that separate one kind of case from another”

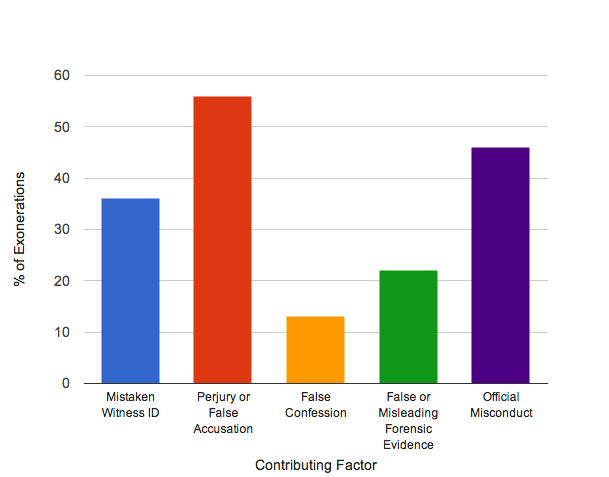

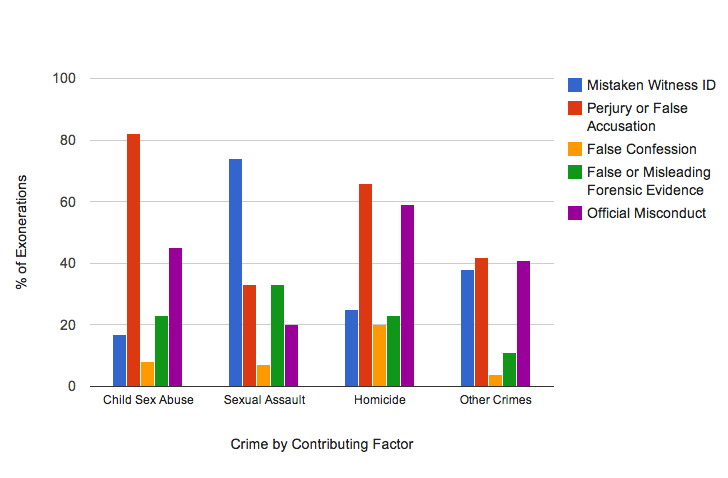

The biggest factor in overall exonerations was perjury or false accusation but this picture is more complicated when analyzed by crime.

As this chart shows the factors involved in a wrongful conviction vary depending on the crime (there may be multiple factors involved). More than 80% of exonerations in child sexual abuse cases, for example, involved perjury or false accusation but that was only a factor in 33% of sexual assault cases. In those cases, mistaken witness identification was a factor in the majority of exonerations.

Mistaken identification was a factor in Phillips’ conviction according to the Washington Post.

The woman who was raped partially pulled up the ski mask on her attacker, and she said she recognized Phillips. She also picked a photo of him out of a lineup. But after an investigation, Watkins’s office determined that the other man was the rapist.

“DNA tells the truth, so this was another case of eyewitness misidentification where one individual’s life was wrongfully snatched and a violent criminal was allowed to go free,” Watkins said in the statement. “We apologize to Michael Phillips for a criminal justice system that failed him.”

Phillips plead guilty to raping the victim, despite being innocent, although he never confessed to the crime. The majority of false confessions occur in homicide cases. Gross says this is a reflection of “the fact that far greater resources are expended on investigating homicides than other cases.” This produces a higher clearance rate “but in addition it also produces a higher rate of false positives, of errors. Put a lot more effort into it you get more convictions you also get a higher number of false convictions.” Just listen to this This American Life episode to hear how some false confessions come about

According to Gross evaluating the effects of reform on the rate of false convictions is complicated because “we don’t know the rates of error to begin with.” That said, Gross argues there are “things that should be done even if you cannot measure their effect because they preserve the integrity of evidence and preserving the integrity of evidence is a basic fundamental value.”

Among the steps he says should be taken are video recording interrogations, “there’s just no justification for not doing this”, and creating better eyewitness identification procedures “to reduce the risk that a potential witness can be influenced by an investigating officer.” There is also an urgent need for more funding because “the way they avoid spending money is to get parties, particularly defendants to agree not to have formal procedures, to agree to plead guilty, and by threatening them with a hammer if they don’t give up their rights.” These kinds of changes are being made, says Gross, “with the definite exception of devoting more money to the system there is a good deal more movement and more flexibility in review and better investigative procedures.”

Overall, he argues, “when substantial new evidence emerges we should be less stubborn to reconsider judgment.”