For weeks the pincer of police, private security and National Guard surrounding the main resistance camp at Standing Rock, in Morton County, N.D., has been slowly closing. On Thursday morning, about 13 days after construction resumed on the final section of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), these state and federal forces moved in to begin clearing Oceti Sakowin, the main camp where thousands of Native Americans and their supporters, who call themselves water protectors, have gathered for months to oppose the project. Several dozen people remained in camp, however, vowing to stand their ground.

As the deadline loomed on Wednesday some people set fire to some of the remaining structures in the camp and gathered on the highway where riot police bearing batons had formed a line. Police did not make mass arrests and appeared not to enter the camp itself. Instead they picked out and arrested people one at a time, including at least one person who was live streaming the incident. According to a statement from the North Dakota Joint Information Center police made “approximately 10 arrests.”

On Thursday morning, however, at least a dozen military Humvees and at least three large armored military-style vehicles assembled on highway 1806 along the western edge of the camp. As a helicopter from the Department of Homeland Security circled low overhead, a massive force of police in riot gear and National Guard, flanked by armored vehicles and bulldozers, marched into the camp. On the other side of camp nine people could be seen joining hands around a sweat lodge where a prayer ceremony was apparently taking place.

How a community formed in opposition

The Oceti Sakowin camp formed in August last year and quickly became the front line in the fight against DAPL. It served as the base for most of the direct actions that slowed construction of the pipeline and drew international media attention to the struggle. At the height of the protests the main entrance to the camp was lined by hundreds of flags from the different Native tribes across the Americas who had pledged their support. In December, faced with an earlier eviction threat, the camp drew thousands of supporters, including military veterans who promised to create a “human shield” around water protectors to defend them from police weapons that included rubber bullets, tear gas and a water cannon in below freezing temperatures.

Tear gas mixes with smoke from a sage smudge behind the police barricade on highway 1806 on January 18, 2016. Water protectors had gathered at the barricade a half mile north of the main Oceti Sakowin camp to demand that the road be opened. (Photo: Joseph Bullington)

Instead of a forced eviction, on Dec. 4, 2017, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) announced it would not issue an easement for the pipeline company to drill beneath the Missouri River until a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) of the project could be prepared. The next day Standing Rock tribal chairman Dave Archambault II celebrated the decision and asked water protectors to leave camp: “They’re purpose has been served,” he told NPR. “Nothing will happen this winter.” Most people left the camps.

Others, however, doubted that the pipeline company and incoming Trump administration would respect the decision. Hundreds opted to stay through the harsh North Dakota winter. When I travelled to Standing Rock in late November there were still several thousand people living in the camp. A system of communal kitchens was serving several thousand meals every day. When you said “thank you” to the people serving the food they would respond “thank you for the work you’re doing out there.” That’s what there was for an economy at Oceti Sakowin.

It was hard to cross the camp without being drawn in to work on a project. This was not a “hippie protest” as some people tried to cast it — apparently without ever having set foot in North Dakota. This was a rural-based resistance movement. People there drove trucks and knew how to run heavy machinery, power tools and chainsaws. They kept horses and knew how to rig up wood stoves and solar panels. I went to work one day helping some carpenters hang plywood sheathing on the 2 by 4 frame of what can only be described as a small, two-story house. The building, which was to be a women’s space, was designed, framed, walled and roofed in a matter of a few days. The Oceti Sakowin camp was a Native-led, autonomously organized community on a scale I had never before seen.

The Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868

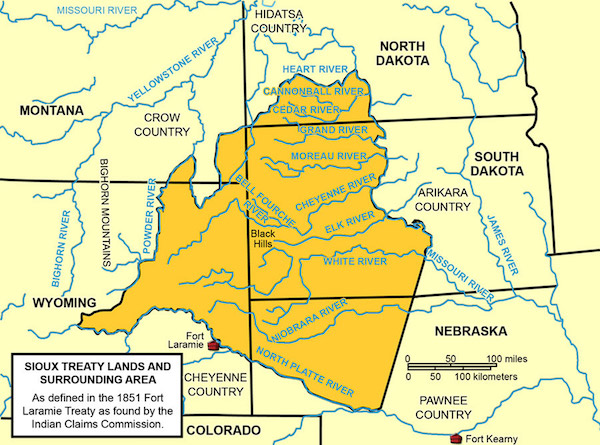

According to maps from the State Historical Society of North Dakota, the land on which the camp sits — along with most of present day South Dakota and much of North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Nebraska — was reserved for the Lakota (the umbrella name for the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota peoples usually referred to as the Sioux) and other local tribes in the hard-won Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868. The 1868 treaty designated “the country north of the North Platte River [in Nebraska] and east of the summits of the Bighorn Mountains [in Montana]” as Unceded Indian Territory. In this country, the treaty reads, “no white person or persons shall be permitted to settle … or without the consent of the Indians … to pass through the same….”

The Treaty of 1851 did not establish a reservation, but began the process of defining territory in which the Sioux could live and hunt. The treaty was supposed to reduce warfare among the Indian tribes of the northern Great Plains. (Image / Caption: ndstudies.gov)

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 created the Great Sioux Reservation (in gray). Unceded lands (in yellow) in Wyoming, Nebraska and Dakota Territory were reserved for hunting. A portion of the unceded lands in northern Dakota Territory became part of the Great Sioux Reservation (later Standing Rock Reservation) following an agreement between the federal government and the Sioux leaders in September 1876. (Image / Caption: ndstudies.gov)

In the 1950s, the federal government seized more land from the Standing Rock Sioux when it built the Oahe dam on the Missouri River. The resulting lake flooded more than 200,000 acres of the Standing Rock reservation and the Cheyenne River reservation just to the south. The tribes lost 90 percent of their timber and much of their best agricultural land. Now, in order for the project to be completed, DAPL must tunnel under the Oahe reservoir.

The land under dispute at Standing Rock, the Oceti Sakowin camp and the land through which the pipeline passes on its way to and under Lake Oahe, lies within the bounds of this unceded treaty territory.

Chase Iron Eyes, a Standing Rock Sioux tribal member and an unofficial leader at the camp, told Democracy Now! that the land was lost as “the result of an illegal annexation of treaty territory by the United States against not just the Standing Rock Nation, but the entire Lakota Nation.”

On February 3, 10 days after President Trump cleared the way for the pipeline via executive order, USACE ordered the evacuation of the camp by February 22, citing safety concerns and “the high potential for flooding.” Four days later USACE announced it would forgo the EIS and issue the final easement to complete the pipeline.

“The Army Corps said that they would declare us trespassers on our own land,” said Iron Eyes, referring to the February 22 eviction deadline. “The same as when the United States Army said they would declare us hostile if we didn’t return to the reservations in 1875.”

Below is some of the latest footage from Standing Rock:

WATCH as militarized police knife open a sheltered structure during their eviction of the main #NoDAPL encampment https://t.co/YDWKf0paPs pic.twitter.com/uuu7eGUt1l

— Unicorn Riot (@UR_Ninja) February 23, 2017

LIVE: About 5-6 Humvees in camp around area that people said earlier they would get arrested in passive resistance https://t.co/R36xX5Yw17 pic.twitter.com/o2nPPcHyV3

— Unicorn Riot (@UR_Ninja) February 23, 2017

[If you like what you’ve read, help us spread the word. “Like” Rural America In These Times on Facebook. Click on the “Like Page” button below the bear on the upper right of your screen. Also, follow RAITT on Twitter @RuralAmericaITT]

Joseph Bullington grew up in the Smith River watershed near White Sulphur Springs, Montana. He is the editor of Rural America In These Times.