For Low-Income Residents, the Economic Benefits of Amazon’s New Wind Farm are Up in the Air

Amanda Abrams

In February, the first large-scale wind farm in the Southeast went online in northeast North Carolina. Created to power Amazon data centers, the 208-megawatt facility will inject almost a million dollars into the local economy annually. But the region is rural, decidedly poor and home to a sizable African American population. Will the area’s low-income residents benefit from any of that new money, or will the facility wind up simply widening the existing gulf?

The Amazon wind project straddles two counties, Perquimans and Pasquotank, that sit on the Albemarle Sound, just inland from the Outer Banks. The region is flat and swampy, with long stretches of corn and soybean fields. The biggest municipality, Elizabeth City, has a charming but deserted downtown and a poverty rate of 30 percent, almost double the state average. The town, which is majority African American, hasn’t fully recovered from the recession; jobs are at the local Coast Guard base or with the state, and there isn’t much else.

Unfortunately, unlike solar projects, wind facilities don’t require many workers to set up or maintain the turbines. “One person on the maintenance side takes care of twelve machines,” says David Swenson, an associate scientist in the department of economics at Iowa State University. “There’s not many jobs created; the traditional working person won’t have access to much.” So employment isn’t a major benefit of the projects.

Aug. 10, 2016 — Two workmen stand on the nacelle (the housing for a wind turbine’s generating components) during construction of the Amazon Wind Farm. The complete assembly of each turbine is 492 feet tall. (Photo: Chuck Liddy / newsobserver.com)

But most wind projects do deliver revenue to a community in two distinct ways. First, landowners receive payments for the turbines they host on their property. In this case, the 60-some property owners in the region are issued $6,000 per turbine per year. That’s a big win for farmers, especially when agricultural commodity prices are low as they currently are; they receive payments but are still able to farm 95 percent of the land.

But despite their perennial difficulties, few landowning farmers are low-income. That’s true here, where the median income for the county as a whole is very close to the state average. “We’re quiet, middle class people. I wouldn’t say anybody’s struggling,” says James White, a farmer in Whiteston who has two turbines on his land. With 200 acres, he’s considered a small farmer. “It’s not a make or break for anyone, just an extra benefit.”

Those payments do trickle down to businesses and others in the community — White and his wife bought a new car and truck in Elizabeth City last year as a result of the forthcoming turbine payments — but the overall economic impact of leasing something out is fairly weak, says Swenson. That means non-landowning folks in the region don’t wind up seeing a whole lot of that money.

It’s the second set of payments from projects like these that really matter to lower-income communities. Wind power developers pay property taxes to counties. In this region, Avangrid Renewables, which built and operates the Amazon wind facility, pays Pasquotank and Perquimans counties $5,000 per turbine. That comes out to around $500,000, which is roughly split between the two counties, and makes Avangrid the biggest taxpayer in both counties.

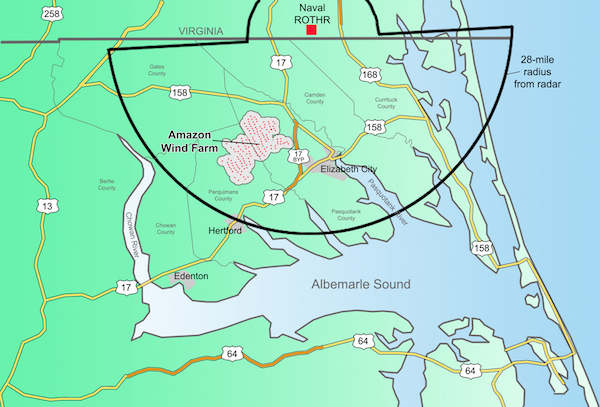

A map of the where the Amazon Wind Farm overlaps Pasquotank and Perquimans counties. The Naval ROTHR is a nearby military long-range radar surveillance station. (Infographic: carolinajournal.com)

Whether poor residents benefit from wind farms depends, by and large, on how a county government chooses to use those revenues. In Perquimans and Pasquotank counties, the new funds are being used to fill holes. “It’s been a very tight economy here, and most agencies have been spending their fund balance down to the allowable level. That $250,000 eases the pain a little bit, but doesn’t create any money for additional initiatives,” says Wayne Harris, economic development officer for Pasquotank County.

County commissioners in this area could eventually make more strategic choices. Elected officials in other regions have used their windfall to lower their tax rates — by half or even more. Low-income residents would most likely gain from that. “Lowered taxes would benefit you even if you don’t pay income taxes or even own property,” says John Rogers, a senior analyst in the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Other communities have heavily invested in schools, with programs that benefit students across the income spectrum. In Van Wert, Ohio, the school system used wind energy money to buy computers for every student and establish new STEM programs. In Lowville, N.Y., revenues from a wind farm funded AP courses, expanded technology and refurbished school athletic facilities.

Of course, poor regions will always have competing priorities — roads that need repaving or jails that are continually underfunded. In Pasquotank County, for example, the school district has been desperate for more funding. This year, the county commissioners had to raise taxes to cover a shortfall in the school system’s budget. Next year, they might be able to use wind power money for that.

But many Elizabeth City residents are dubious that they’ll ever see that money. A rumor has been going around that the wind power funds won’t stay in the state, says Nancy, who doesn’t want to use her last name. She’s a longtime Elizabeth City resident who recently moved away when the house she was renting was condemned. “A lot of us have been told that the wind farm would only benefit people outside of the area,” she says.

Others simply don’t trust their county government to do the right thing. Douglas Britt, owner of D&J Woodworking, is skeptical about how the city will manage the new funds. “I’m for it; I just wish we’d get a little more money.”

The upshot? Low-income people could see real benefits from new wind power revenues — but they’re going to have to push for it and advocate for themselves.

Meanwhile, the state of North Carolina is proving to be the biggest barrier to economic development: The state legislature recently passed an 18-month moratorium on new wind farms across the state. Legislators say they’re concerned that the turbines might interfere with aircraft activity at nearby military bases, which provide a major economic boost to the eastern part of the state. But wind energy projects must already pass rigorous Defense Department and FAA reviews before approval, and many observers think money from the petroleum industry is playing an influential role. Two more facilities have been in development in northeastern North Carolina, but now the residents there will have to wait even longer to see benefits flow to their depressed regions.