In the midst of World War I, Rudyard Kipling declared, “There are only two divisions in the world to-day — human beings and Germans.” That mindset was not unique to Kipling, and made it easier for the other European powers to bomb German cities, poison German soldiers in trenches, riddle their bodies with bullets and stab them with bayonets. But if the Germans weren’t human, what were they?

Environmental historian Edmund Russell uses a simple word for “everything other than people and their creations,” a category into which Kipling might have placed the Germans: “Nature.” By casting the Germans as a “natural threat,” Russell writes, propagandists were able “to transform killing from a moral issue into a natural response.”

In his 2001 book, War and Nature: Fighting Humans and Insects with Chemicals from World War I to Silent Spring, Russell documents the interconnected rise of chemical warfare and chemical insecticides, and compares the power structure and priorities of American society at war and at peace. He uses this chemical case study, adapted from his doctoral dissertation in history at the University of Michigan, to push a broader thesis: “War and control of nature coevolved: the control of nature expanded the scale of war, and war expanded the scale on which people controlled nature.”

He is not the first to connect war and control of nature. In 1976, for example, historian Murray Morgan wrote of deforestation, “It was strangely like war. They attacked the forest as if it were an enemy to be pushed back from the beachheads, driven into the hills, broken into patches, and wiped out. Many operators thought they were not only making lumber but liberating the land from the trees.”

The parallels still exist today, if we care to notice, and warring nations do not factor nature into their collateral damage reports. A recent Truthout/TomDispatch report exposes potentially disastrous ramifications for arctic wildlife due to the Navy’s planned war games. Hundreds of thousands of marine mammals’ lives will be disrupted, including dolphins, sea lions, and several species of whale. At least a dozen native tribes make their home in the affected region of Alaska and expected damage to local fish populations, salmon in particular, poses a severe threat to their traditional diet and way of life. For the indigenous humans (and indigenous nonhumans), these “games” are anything but.

The war on nature in Russell’s book is more than just a metaphor. When chemical pesticides were first introduced, the goal was annihilation and insects were explicitly cast as an opposing military force. During World War I, one entomologist writing in the Chicago Herald referred to “fifty billion German allies” damaging America’s crops.

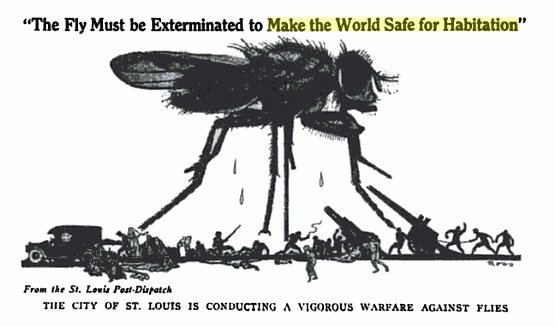

In the words of L.O. Howard, the chief of the U.S. Bureau of Entomology, these German allies called for “warfare against insect life” —and, naturally, more funding for his bureau. A newspaper cartoonist got specific, demanding the extermination of the fly. He depicted a giant fly under siege from human cannon fire, writing in his caption that this war would “Make the World Safe for Habitation.”

Four years after the Great War, Century Magazine described humanity’s need to eradicate insects as “a warfare that will know no armistice. Man’s civilization, his future, his very life are at stake.” In 1925 Harper’s took an equally apocalyptic tone. “The issue is vital: no less than the life or death of the human race.”

The weapons used were closely tied to their time period: World War I had seen the first systematic use of poison gas and what worked in the trenches often worked on the farm. The war was a “Cinderella-like transformation of the American chemical industry,” and after the World Wars, synthetic organic compounds used for defoliation, to make weapons and as insecticides to protect troops were promoted and sold for use in the civilian market.

Arsenic, a natural mettaloid, has a long history of use as a pesticide, herbicide, paint pigment, medicine, wood preservative and human poison. Before the Great War began, arsenic was the base of most widely used pesticides. Of course, arsenic isn’t just bad for pests. It also killed insectivorous reptiles and, as one insecticide maker put it, our “most beautiful and faithful allies the birds.” Synthetic chemicals developed during World Wars I and II were thought to be safer for vertebrates while more devastating for insects. Instead, pests quickly developed resistances to the pesticides, so more and stronger poisons were used. Birds and other insect eaters were exposed to the poisons, without resistance to them, as were humans, causing illness and death

Russell attributes the long-term failure of pesticides to a fundamental difference between peacetime and war. While his historical narrative is consistently compelling, his argument here is perhaps the most effective part of the book. In war, he reasons, soldiers are often on the move. If pesticides left a site with long-term consequences — as some did — this did not matter to the soldiers, who (if they survived the battle) were presumably long gone when the residual damage manifested. In the thick of battle, the preservation of wildlife is not the highest priority. What mattered was immediate threat elimination — urgent, momentary control of the natural world.

In peacetime, on the other hand, people aren’t advancing on or retreating from an enemy — we settle down in a particular spot. Farmers work the same land for years, and even low levels of pesticides add up. Slight disruptions to the ecosystem can lead to disastrous ramifications over timescales too large to be relevant in human warfare.

The other key argument in Russell’s story is that “peacetime” became less and less defined over time. In the aftermath of World War I, eras of peace seemed distinct from those of conflict. But this began to change over the interwar years and, by the time the Cold War began, whatever lines remained were irreversibly blurred.

A collusion of government and industry interests were central to solidifying what we now call the “military-industrial complex.” Perhaps more surprisingly, academia was also an eager collaborator. Public opinion opposed chemical warfare after World War I, but the American Chemical Society was an influential cheerleader. Chemists proved to be stubborn political obstacles to any sort of arms treaty limiting poison gas. We all know that physicists helped develop the atom bomb — but in the story Russell tells, the “workhorses” of war were the chemists.

The Army’s Chemical Warfare Service kept busy during the interwar years doing what they called “peace work,” but this work was not peaceful for everyone. They sent chlorine gas into gopher holes, poisoned rats and earthworms and supplied tear gas for use against civilian protesters.

The relationship worked both ways: Chemicals and institutions developed for war were effective against nature, and the control of nature in turn would lead to weapons of war in World War II. “The flexibility of insecticide research posed a tremendous challenge to anyone who wanted to abolish research on chemical warfare,” Russell writes. You can’t research one without the other. As Major General William Porter, chief of the Chemical Warfare Service, so chillingly observed in 1944: “The fundamental biological principles of poisoning Japanese, insects, rats, bacteria and cancer are essentially the same.”

Notice that Porter does not mention the Germans. The Nazis as a group received a huge amount of vitriol, but as a nationality the Germans were much less hated than the Japanese. In the Pacific Theater the most deadly killer was insect-borne illness but, according to the propaganda machine, mosquitoes weren’t the only insects.

Military cartoonists portrayed the Japanese as arthropods with grossly caricatured features, with accompanying text often bordering on genocide: “This louse inhabits coral atolls in the South Pacific … But before a complete cure may be effected the origin of the plague, the breeding grounds around the Tokyo area, must be completely annihilated.” Insecticide companies joined in, putting the heads of Hirohito, Hitler, and Mussolini on bugs in advertisements.

The chairman of the War Manpower Commission, four months before the atomic bombs dropped, called for “the extermination of the Japanese in toto.” The growth of more impersonal means of warfare — dropping bombs from planes instead of stabbing with bayonets — also helped rob the enemy of any humanity. The explicit racism of the dehumanizing Allied propaganda incited disgust for the Japanese and fear and hatred of insects. For both groups, America’s loathing had consequences both at home and abroad.

After World War II Russell takes us down two concurrent paths: one of war and one of human’s attempted control of nature. He shows how the two became joined, with their concomitant economic, social, health, and environmental problems. The first follows the Cold War and the ever-growing power of war-related industries and bureaucracies. The development of “total war,” in which all citizens contributed to the war effort and all citizens could be targets, had eroded traditional lines between civilian and military, culminating in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1960 “military-industrial complex” speech.

The other path bears witness to the devastating effects of many pesticides on wildlife (not to mention farm workers), and the often unsuccessful attempts by industry to keep up with evolution as many insect species developed pesticide resistance. These failures culminated in Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, largely credited as the wake-up call that inspired the modern environmental movement.

These two paths intertwine, as Russell’s narrative demonstrates — failed pesticides are reworked as nerve gas for use in Korea, fighter planes are repurposed to douse chemicals across American fields. He leaves the reader with the powerful notion that, while on the surface Eisenhower and Carson were responding to two different phenomena, their underlying messages had much in common.

Here we are 14 years after War and Nature was published, half a century after Silent Spring, and the mighty influence of the military-industrial complex and chemical agriculture are as strong as ever, perhaps stronger. The early warnings that pesticides might upset the “balance of nature” or the “biological balance” have grown into an entire environmentalist vocabulary and movement. The ideas have gone mainstream, but solutions seem harder to come by.

Russell shows that the “war on nature” was a carefully orchestrated and executed post-war plan by the federal government and chemical industry. It supported the consolidation of farms and the industrialization of agriculture. It helped separate us from the production of our food, but kept the physical link between us and the poisons.

His book also presents powerful and exhaustively researched evidence of the ecologist’s mantra that “everything is connected.” The language of the warmongers and chemists may classify humanity as outside of nature, but Russell’s research shows that our health, social, and political realities are inextricably tied to the nonhuman world. We must make peace on both our cornfields and our battlefields — or find peace on neither.

(Sign up for the Rural America In These Times newsletter at the top of this page to be notified of more stories like this one.)

Dayton Martindale is a freelance writer and former associate editor at In These Times. His work has also appeared in Boston Review, Earth Island Journal, Harbinger and The Next System Project. Follow him on Twitter: @DaytonRMartind.