Commercials featuring upbeat music, smiling farmers, and anthropomorphized chickens — ads generated by companies like Foster Farmers and Pilgrim’s Pride — help make customers feel good about buying some of the nearly 40 billion pounds of chicken produced annually in the United States. But the reality for chicken farmers across rural America is much less pleasant than that depicted on television.

A set of rules proposed under the Obama administration by the Department of Agriculture’s Grain Inspection, Packers, and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) — known as the Farmers Fair Practice Rules — would provide contract farmers with basic protections and a larger voice within the industry.

The Trump administration, however, has delayed their implementation several times and the future of the rules is uncertain. In the meantime, farmers say they’re not getting a fair deal, and they want the federal government to take action.

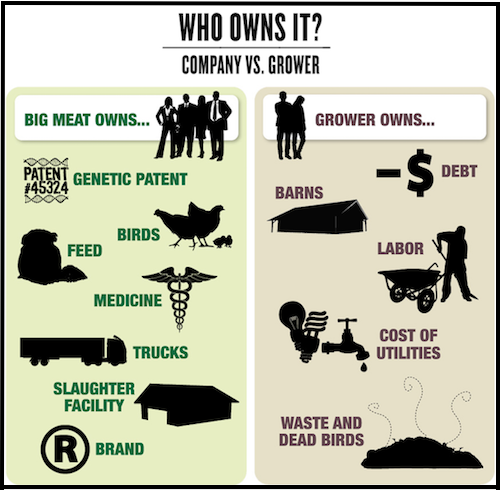

According to Barbara Patterson, government relations director at the National Farmers Union, the story of the modern chicken industry started around 50 years ago with something called vertical integration — an arrangement where instead of a small farmer buying feed from one supplier, supplies from another, and sending chickens to a slaughterhouse when they mature, one massive company owns the entire supply chain, with nearly total control.

(Source: foodopoly.org / farmaid.org)

Tyson Foods, a pioneer in the field, endeavored to control every aspect of its broiler chicken supply chain — from feed production to shipment to markets, and other chicken producers followed suit. Such companies are known as “integrators,” a reference to their core business model. The National Chicken Council, which represents large integrator companies, advertises integration as a benefit for consumers: “The efficiency of this system has helped foster lower real prices for chicken products.”

Indeed, per pound pricing for chicken has remained extremely low, according to United States Department of Labor statistics, but that’s come at a cost to farmers. The one thing integrators like Tyson don’t own is the chicken farms themselves — these, along with costly infrastructure like chicken houses, remain in the hands of farmers, known as “growers,” who produce chickens on contract. Today, 97 percent of the chicken consumed in the United States is grown by contract farmers.

Patterson says that on its face, contract farming isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Capital investments are costly, but contracts can provide financial security for farmers, with integrators providing chicks, feed, and veterinary services in exchange for a guarantee that they’ll buy the end product. Because chicken is a perishable good, farmers are known as “price takers” — they have to take whatever price they can get, because their chickens will spoil if they do not get to market — which could put them in a bad bargaining position without a contract that guarantees that they can sell their chickens at a fair price once they’re mature. The operative phrase here is “at a fair price,” which is not, farmers say, what the chicken industry is offering.

Broken promises and financial struggle

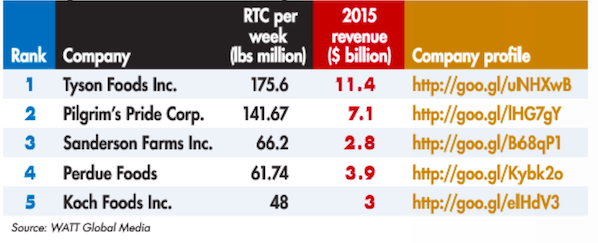

These days the chicken industry isn’t a competitive market. Five integrators dominate the industry, leaving farmers with few options. And the business of raising chickens, it turns out, gets quite dirty. The problem, farmers say, is the bizarre and complicated “tournament system,” in which farmers are pitted against each other to determine who can produce the most meat at the least expense.

Tyson Foods Inc. is the largest chicken company in the United States and one of the largest food companies in the world. To view a full list of the top 34 domestic broiler chicken producers and to learn more about their production, click here. (Source: poultryinternational-digital.com)

Multiple farmers in a region are known as a “complex,” and will raise flocks at the same time. When the chickens are brought in, their end weight is tallied against the cost of feed and supplies used to determine who was most efficient — those who raise chicken cheaply get a premium, while those who don’t get financial penalties. Integrators say this keeps costs down for consumers, but it also creates wildly fluctuating income for farmers because the cost per flock can vary in ways that some farmers claim are unjust.

Mike Weaver grows chickens in Virginia for Pilgrim’s Pride, serves as president of the Contract Poultry Growers of the Virginias and sits on a number of boards, including that of the Organization for Competitive Markets (OCM). He says his income from flock to flock can vary by thousands of dollars. He raises about six flocks a year, and says he’s in the fortunate position of not having to rely on them as a primary source of income. The 65-year-old retired federal agent tells Rural America In These Times, “Had I known that the income would stay the same now as it was 16 years ago, I wouldn’t have done it.”

Mike Weaver, a retired Special Agent for the U.S. Department of Interior, owns and farms 350 acres in Pendleton County, West Virginia, raising angus beef cattle and broilers for Pilgrim’s Pride. For Weaver’s full bio, click here. (Photo: competitivemarkets.com)

He’s not alone. Alton Tom Terry, 53, a former chicken grower living in Tennessee, received his degree in agricultural economics from Texas A&M and spent years researching the industry. But once he actually started growing for Tyson, Terry found the picture was very different than that promised when he signed his contract. “They can give me such low pay,” he says, “that it can bankrupt me.”

Patterson at the National Farmers Union says integrators systematically prey on poor rural farmers with few industrial opportunities and market the promise of chicken farming as a way to generate income. She says the farmers they work with put it this way: “The companies just lie.”

Foul play in the stockyard

Many chicken growers in the United States, particularly those relying on poultry as a primary source of income, live below the federal poverty level. (According to OCM, the number is a whopping 71 percent.) As a result, Sally Lee of the Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI) says she routinely hears from growers struggling with bankruptcy, losing their homes or otherwise enduring tremendous financial stress. In 2001, a Texas grower named Barry Townsend stormed the Sanderson Farms regional headquarters in Bryan, Texas, shot and killed a manager, wounded another employee, and then killed himself. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which tracks mortality rates by occupation, farmers in the United States have a disproportionately high suicide rate. In 2012, people working in the farming, fishing, and forestry group had the highest rate of suicide overall—or nearly six times higher than the general population — with about 84 suicides per 100,000 farmers contrasting the roughly 13 suicides per 100,000 that occured in the population at large.

But growers say that when they speak out to complain about conditions, they face retaliation. Weaver reports that he’s been taken out of the flock rotation in addition to receiving bad feed and chicks. Lee says RAFI has experienced reports of abrupt termination of contracts and outright fraud, including practices like not weighing chickens in correctly. Terry sued Tyson Foods over their refusal to allow him to watch them weigh his chickens in. Terry says he’d previously tried to push the company to abide by the rules of the 1921 Packers and Stockyards Act. The 53-year-old’s case fizzled out, despite the fact that both the Bush and Obama administrations had filed amicus briefs, he says.

“It seems like family farmers just can’t catch a break right now,” says Patterson. Farm revenues are projected to drop nine percent from 2016, across all sectors, and the value of farm assets is declining as well. The increasing corporate consolidation of agriculture and the increasing power of big ag lobbyists is making it even more challenging for farmers to navigate the changing face of agriculture.

One glaring problem with poultry farming industry is that the 1921 Packers and Stockyards Act hasn’t kept pace with developments in the field and the USDA’s Grain Inspectors, Packers, and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) has failed to adequately oversee industry issues. That’s why farmers are pushing for the GIPSA rules, popularized recently as the Farmers Fair Practice Rules, which would clarify the scope of the law.

The USDA’s regulatory solution

Three rules are currently under consideration.

One, an interim final rule — one theoretically designed to go into effect immediately, pending compelling comment to the contrary — would allow contract growers to bring suit against integrators without a burden of proof for “competitive injury.” Currently, a grower who feels wronged by an integrator must demonstrate that a given practice is injurious to the industry as a whole — a nearly impossible task, as it requires a farmer to show how harm done to one farm damages every chicken grower in the industry. Lee puts it this way: “If I go and burn your house down and you want to take me to court, you would have to prove that my burning your house down affected the price of every house in the Southeast.”

A second proposed rule provides oversight of the tournament system, with remedies for farmers who feel they’re being treated unjustly.

A third proposed rule defines what constitutes unfair practices and undue preferences, a move designed to protect farmers from inequalities in their dealings with integrators.

The path to developing the GIPSA rules has been long and torturous. Shortly after taking office in 2008, the Obama Administration directed the USDA to begin preparatory work, which included town halls and solicitations for input across the country. Reporting in 2015, Last Week Tonight’s John Oliver noted that many growers didn’t show up at those town halls out of fear of retaliation from integrators.

(Video: YouTube / LastWeekTonight)

In 2011, the USDA finally issued early drafts, but the GOP Congressional leadership added a rider to the House Agricultural Appropriations bill making it impossible for the USDA to spend government funds on activities related to the rules — effectively making it impossible for the agency to continue developing the rules, let alone introduce them for public comment. Farmers claim that investigative journalism like Oliver’s coverage brought the issue into the public eye, forcing Congress to change direction, though pressure from organizations like RAFI also likely played a role.

Shortly before the transition, last December, the Obama Administration published the rules in the Federal Register, with a 60-day deadline for the interim final rule to go into effect, and a 60-day comment period for the two proposed rules.

On January 20, the GIPSA rules were derailed with President Donald Trump’s regulatory freeze order, which automatically created another 60-day extension for the GIPSA rules. On April 11, USDA delayed the implementation of the interim final rule pertaining to burden of proof for lawsuits by another six months, saying they needed more time to hear from “stakeholders” on rules that have been in development for nearly a decade.

The USDA is asking for public comment on four possible alternatives: Suspend, withdraw, delay or enact the interim final rule. This raises the possibility that the agency is considering ditching the rule altogether, leaving farmers and advocates back where they started.

Meanwhile, the fate of the two proposed rules remains up in the air, as the comment period has just closed and the USDA will determine whether the two proposed rules move forward.

Industry says farmers are happy, laments “government interference”

The poultry industry is delighted by this news, having previously referred to the proposals as “draconian.” Tom Super, a spokesman for the National Chicken Council, claims “the vast majority of chicken farmers in rural America are happy,” and says the rules constitute government interference. Patterson disagrees, noting that there are benefits to the rules for producers, including better relations with growers who may feel more confident about negotiating contracts that benefit both parties, more confidence from members of the public concerned about farmer welfare, and greater legal clarity when matters do progress to court. “If companies are doing the right thing,” says Lee, “they should have nothing to worry about.”

Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue (only recently confirmed and no relation to the chicken aggregator dynasty) has a lot of big ag’s money backing him. All the same, Patterson and other farming advocates are hoping the USDA will move out of stasis now that the agency has a boss, and progress with reforms to improve conditions for contract farmers. But given Perdue’s history and financial backing, when he does kick the agency into gear, it may not be in favor of small farmers who are already feeling burned by the Trump Administration.

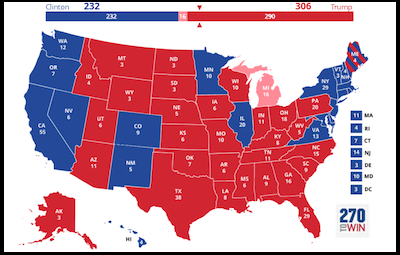

Electoral map of the 2016 election by party:

Eight of the top ten states for broiler chicken production, which are almost exclusively grown under contract, supported President Trump and are some of the most rural states in the country. (Maps / Caption: National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition)

Lee says RAFI is disappointed to see that the Trump Administration appears to be pulling back on the rules, despite his campaign promises of bucking the Washington establishment and draining a lobbyist-filled swamp. “It could be an indication that, again, farmers are going to be ignored and their voices will be silenced in the name of lobbyists and big business,” says Lee.

“We thought that President Trump would be competent enough, and strong enough, to say no to the established parties that were doing these kind of things, but no,” says Terry, who says he voted for Trump in a belief that he’d enact change. The frustrated farmer notes that fixing the broken system for farmers would make American great again.

“He came out and campaigned for the little guy,” says Weaver, who also supported Trump in the 2016 election. Now, Weaver says, he’d just like a chance to talk to the president, or to Secretary Perdue, “to voice our side of these issues.”

The big picture

Chicken isn’t the end game here. Instead, chicken acts as a proving ground that demonstrates the marketability of contract farming for other arms of the agriculture industry, a process Lee calls “chickenization.” Already, similar practices are spreading into the hog industry, where a growing share of animals are raised by contract farmers, and beef is also experiencing a similar radical shift.

The chicken, as it were, is the canary in the coal mine.

“We’ve tried to warn the agriculture community that [contract farming] is not a good thing for farmers and you don’t want it,” says Weaver. Without the GIPSA rules, these industries will be left similarly unprotected, with few options for family farmers who feel they are being treated unfairly by the corporations they work with.

In 2014, Craig Watts, a poultry grower in Fairmont, North Carolina, set out to expose the dark side of corporate contract farming. Perdue Farms promptly retaliated with an attempt to discredit him. To read his story, click here. (Photo: farmaid.org)