If country music is really music from “the country”―as in rural spaces anywhere between Portland, Oregon and Portland, Maine―why does nearly every country performer, living or dead, sing with a southern accent, regardless of where they came from?

Since we’re having a “yeehaw moment” as a nation, thanks to the new Ken Burns documentary “Country Music,” let’s dig into this question―because the answer might change how we think about country music, where it comes from, and who, so to speak, owns it.

The southern accent itself has, puzzlingly, taken on a second life as the voice of universal rurality. Why? Rurality clung on longer in the South than other places because of poverty―a poverty that was the result of the evils of slavery, the destruction of total war, and an ensuing era of brutal white supremacy and economic strife. The destitution of the former Confederacy served to preserve the use of instruments and melodies that were common in every corner of this country, until the tide of industrialization swept over these older music forms almost everywhere else, inadvertently isolating and enshrining the haunting songs of yesteryear in old Dixie.

The forgotten corners of the southeast harbored people singing and playing songs from distant centuries and even more distant continents. The seemingly incongruent traditions of Gaelic Europe, Native America, West Africa, Hawaii, Latin America and French Canada collided to create a kaleidoscope of vernacular music forms that coalesced into what we know today as blues, jazz, ragtime, Cajun, zydeco, bluegrass and, yes, country. By the time this music reached the ears of the rest of America in the early 20th century, crackling from primitive phonograph records and fledgling radio stations, these accidentally preserved remnants of speech patterns and musical traditions seemed archaic and novel.

This is an oversimplification of a complicated exchange but it lays out at least the bones of the story. The far-flung southern diaspora―refugees from Jim Crow along with the occasional waves of displaced people driven outward by crop failures and dust bowls―carried with them a nostalgic desire for the music of the region they had escaped. As detailed in the Ken Burns film, record companies and radio stations broadened their audience by purposefully rebranding the vernacular musical traditions of the southeast as the soundtrack to every rural space of this country. The commodification of this cultural nostalgia for a rural way of life is plain as day in the very phrase “Country Music.” What were once called “hillbilly” records were re-marketed as “Country and Western.” (Though the rebranding wasn’t seamless―Hank Williams, the patron saint of “country music” insisted that he was a “folk singer.”) In popular culture, the southern accent―the accent of a region that historically perpetuated racial violence and oppression―became understood as the universal accent of rurality. Rather than acknowledge the diverse and complicated origin of these uniquely American musical forms, the audience was guided toward the illusion of a shared national identity in rural whiteness. The consequences of this whitewashing can still be heard and felt in the radio country of today.

Consider this: The origins and formative musicians of what we now call the blues are entirely as rural and Southern as anything that’s ever come out of Nashville, yet because of the legacy of the “race records” of the 1920’s and 1930’s, early black performers and what became “country music” were segregated―presented and marketed as entirely separate and wholly incompatible parallel genres rather than overlapping and complicated traditions that borrowed heavily from one another. The comfort with which white recording interests have historically stolen creative property from black America is well documented. Elvis’s unacknowledged plagiarism of “Hound Dog” from Big Mama Thorton is mirrored by the radio country of today, which increasingly resembles contemporary hip-hop and pop-music in both style and production, presumably as an effort to garner relevance in an America that is increasingly less white. The cherished steel guitar audible in every hit country song is the descendant of a Hawaiin instrument. The guitar itself is a relative newcomer, entering the story of American music by way of cities and the Latin Southwest. Whatever way you cut it, white America did not create country music―and yet that’s exactly what we’re led to believe.

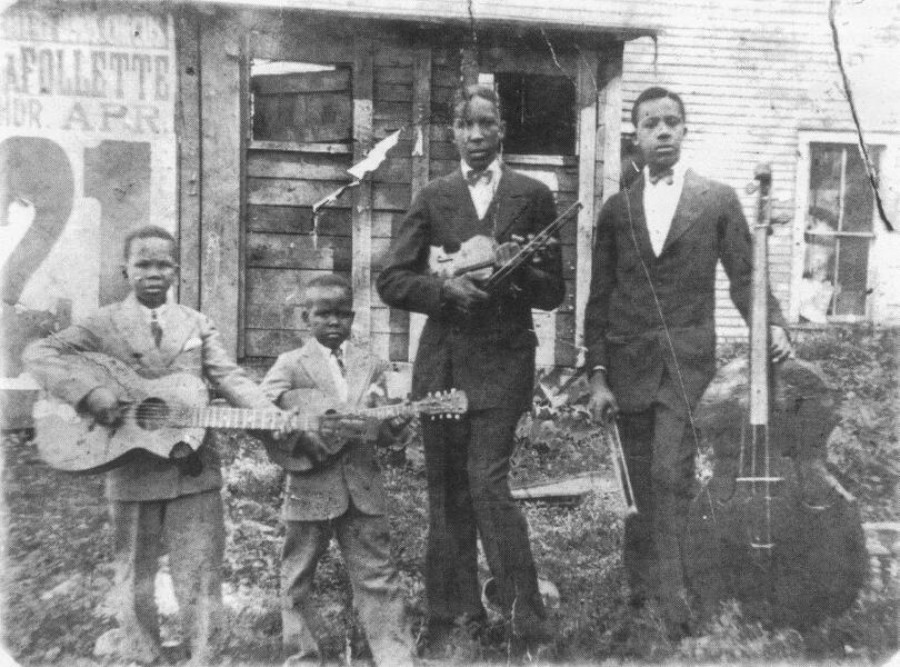

Fiddler Howard Armstrong, second from right, was one of many black string band musicians and country-music forebears who played for both black and white audiences in the 1920s and 1930s. Record companies, however, chose to segregate “black music” (the blues) from “white music” (country).

This reflects a larger problem: The story we tell of “Rural America” in this country is a largely white story, and the rebranding and proliferation of country music to fit a universal rural audience inevitably whitewashed its diverse history and ignored the fact that much of the rural south is anything but white. Take, for example, the life-story of the most American of instruments. What we call a banjo today is an amalgamation of West African gourd instruments that made their way here in the hands of forcibly enslaved people brought to the U.S. in its colonial infancy. Once an instrument of the most oppressed rung of American society, the banjo gained national exposure when racially demeaning black-face minstrel shows toured the country, singing and playing music from the southern cannon by way of parody, inadvertently creating a national craze for the instrument. Decades after this fad had waned, the majority of banjo players that were documented by the folklorists of the 1930’s and on were white players in the upland South, where rugged isolation and poverty had preserved aspects of vernacular banjo traditions rooted in their distant African origin. This selective documentation created the lasting and baseless connotation of the banjo with rural whiteness, ignoring the nuance and reality of the actual meeting between European melodic structures and the rhythms and mechanics of West African music.

As a result of this whitewashing, our culture has largely surrendered country music to the domain of white conservatism. This association creates an understandable view of country music fans as right wing militants, blind patriots and adamant racists or, more generally, celebrators of nostalgia and rigid whiteness―in short, an image that garners suspicion and mistrust from coastal contemporaries and rightfully wary minorities.

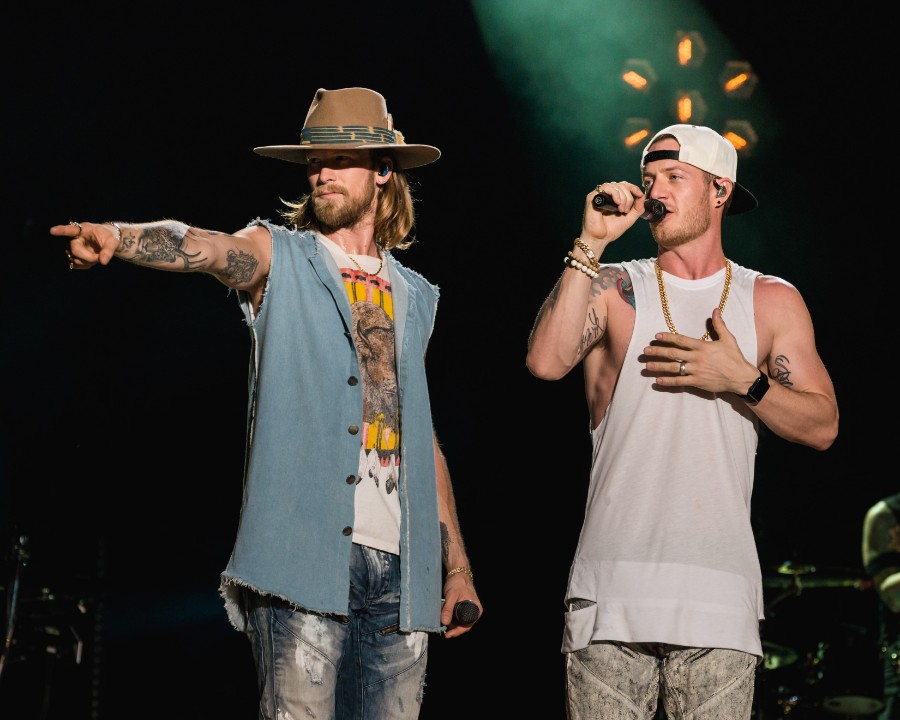

The band Florida Georgia Line performs during the 2017 Country Music Awards Music Festival in Nashville, Tennessee in June, 2017. (Photo by Richard Gabriel Ford/Getty Images)

What we think of as “traditional country” did not originate with white conservative men — far from it. And yet, as a consequence of marketing, that is the dominant perception people have of the genre: That it’s not made for everyone and that it stands not for combating disenfranchisement but for preserving it.

The accent of the former confederacy, as spoken both by black and white southerners, is born in part of past violence and isolation, and so it is problematic when those from outside the region try to adopt it, no matter how benign or performative the intention. Faking what we refer to as “the southern dialect” isn’t just a form of poverty drag; the racial and class implications are overlooked by most people involved in the genre today, regardless of political leaning. Long perpetuated classist stereotypes about the region are rooted in a reality created by fantastically tragic circumstances, dark histories that were ever present to those who grew up confronting every day both the modern rural south and the tense reality of its sinful past.

The basic impression I want to leave is this: American traditional music doesn’t belong to anyone exclusively and never will, least of all white male southerners like myself.

That being said, this music and its region of origin deserve more than stale nostalgia and condescension from academia. It needs to be weaponized against the disenfranchisement it was born from and wielded consciously by people who care about history over mockery. I see it happening by the hands of my contemporaries every day. There’s a plethora of young performers reimaging older music forms to fit a changing world, and among these, a wave of contemporary black performers that have chosen to reclaim the banjo and fiddle from the clutches of revisionist history and make the instruments’ use more than novel and academic, but a part of the national conversation about country music. The definition of “American traditional music” is growing to include the voices of more than white Appalachiaphiles and to more accurately introduce Native and immigrant histories into the consciousness of traditionalist circles. In New Orleans, I’m privileged enough to two-step and yodel in the most vibrant and least white country-music scene in the United States, and it makes me proud to love this genre, despite the darkness. There’s a ton of work left to do to make this unique music form more accessible and more welcoming to people outside of the white rural experience, but we’ve come a long way.

I’ve chosen to own and carry on this tradition in my own music out of obligation to its elevation, not allegiance to a false mythology. But I don’t expect this level of awareness from anyone who ever wanted to sing a sad country song.

That’s my own absurd effort to reconcile. You’re welcome to write songs about tractors, just don’t buy the bullshit: It’s the echoes that are worth keeping, not the rocks they bounce off of.